There was a remarkable episode at a House subcommittee hearing on April 28, convened to explore the high underwriting fees levied upon Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

Two participants took an unexpected line —

The principal driver of advance refundings is the illusion of savings. Under “favorable” conditions, the municipality would issue a second tax-exempt bond prior to the call date of an outstanding tax-exempt bond, use the proceeds to defease the outstanding issue to the call date, and save an impressive amount of interest, whose true source we will discuss momentarily.

As a by-product of this transaction, two tax-exempt issues would support a single qualifying project until the call date, resulting in the proliferation of tax-exempt debt. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act put an end to the game, by eliminating the use of tax-exempt debt for advance refunding.

But canny bankers found a way to show mammoth savings by using taxable bonds instead. For example, in February the

The source of the remarkable savings is the standard muni structure: 5% coupon, callable in year 10 at par (See

Why callable at par? The old-fashioned rationale for the call provision was to enable the borrower to save interest by refunding when rates are lower. The coupon of a bond issued at par is an indicator of the interest rate at the time of issuance; refunding such bond via a par call will be beneficial only if interest rates decline.

But such is not the case in the arcane world of munis, where the 5% coupon doesn’t even tell us whether the interest rate at issuance was 2%, or 3%, or 4%. The only thing we can be sure of is that refunding a 5% bond will save a lot of interest even if rates increase, as long as they stay below 5%. Suppose the municipality issues 5% bonds at a premium, instead of 3% bonds at par. If rates subsequently increase from 3% to 4%, the municipality refunding the 5% bonds, at a considerable transaction cost, captures impressive savings to wild cheers. Surely this was not the intended purpose of the call provision.

The par call virtually guarantees that a 5% bond will be called by the end of year 10, and possibly advance refunded years earlier, to the delight of the transacting infrastructure. If you’re in doubt, just try to find 5% non-call 10 bonds issued before 2011. The par call enables the municipality to report “savings” to its constituents, no matter how rates evolve. This may be good PR, but it is poor finance. In fact, many of these refundings were not as great as portrayed. The low escrow yields ate into the savings, and usually waiting to do a current refunding would have saved more money (See

In short, it is the par call, rather than the 5% coupon, which is the source of the huge interest savings. The 5% bonds will almost certainly be called in year 10, but the savings calculations are based on the nominal maturity date. The public is unaware of the substantial transaction cost of repeated refunding issuances, not to mention the high upfront cost of the par call. Today the price of a AAA 30-year 5% bond with a par call is 130. Consider the revolutionary idea of raising the call price in year 10 so that refunding will be beneficial only if rates actually decline. Just how high would the call price have to be? At the current historically low interest rates, the initial call price of a 30-year bond would have to be roughly 150. But the higher call price would increase the market price from 130 to 140, resulting in a painless 7.7% reduction of the principal amount and the corresponding interest payments — fewer refundings and less cheering, but solid debt management.

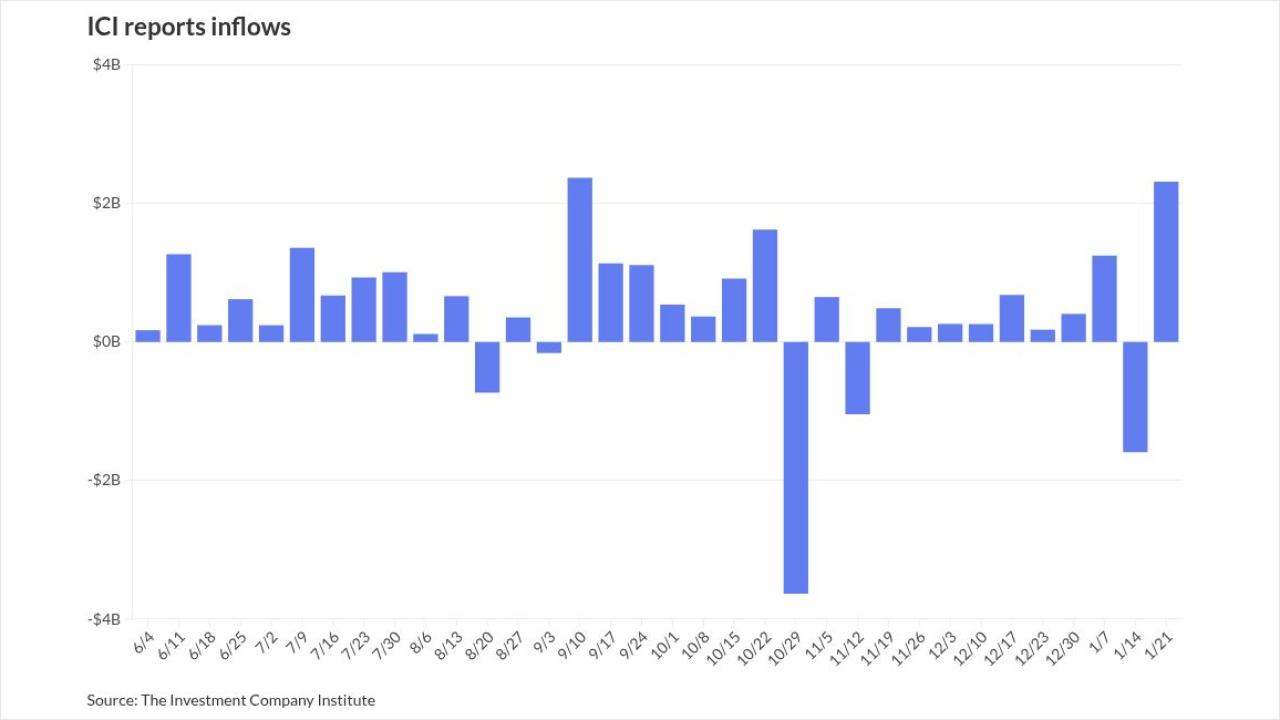

Given the focus of municipal issuers on showing “savings,” without consideration of the cost, it is a safe bet that restoring advance refunding would open the flood gates on not-yet-callable high coupon bonds. Much joy on the part of the issuing infrastructure is sure to follow (See

The restoration of advance refunding (an off-topic discussion at the hearing) will do nothing to reduce the high fees charged to HBCUs. What it will do is perpetuate transactions that deliver illusory savings at high transaction costs.