Private investment in the reconstruction of the Bahamas after Hurricane Dorian could set a precedent for storm recovery in the United States.

Resilience expert Alan Rubin, a principal with Blank Rome Government Relations in New York, discussed the matter in Washington recently with U.S. Rep. Eliot Engel, D-N.Y.; Engel’s chief of staff, Bill Weitz; Eric Jacobstein, senior policy advisor for the House Committee on Foreign Affairs; and representatives from the international development agency U.S. Agency for International Development, which sent a response team to the Bahamas.

“There are fundings that come from both USAID and the [United Nations],” said Rubin, nicknamed the “Hurricane Czar” for his recovery plan for South Florida after Hurricane Andrew struck in 1992. “This is one place where private investment might be the first monies in as opposed to in the U.S. where [the Federal Emergency Management Agency] is involved, and then you get U.S. money that’s allocated out of Congress.

“In this particular case, there could be private investment in companies that are doing disaster recoveries, to put the money in first, and then receive monies back from USAID,” Rubin added, “So this is very different than a public-private partnership.”

Domestically, states and cities have begun to factor climate risk into budgetary and other planning.

Storm activity has been especially intense this season. Severe flooding from Tropical Storm Imelda pummeled East Texas and Louisiana Wednesday and Thursday while Hurricane Humberto knocked out 80% of Bermuda's electricity. In all, six named storms have been spinning in the Atlantic and Pacific.

Dorian, which killed at least 52 people in the Bahamas,

Needs vary by region. New York City, with 578 miles of coastline, has launched a $20 billion worth of resilience initiatives. Wildfires engulf California and tornadoes worry Kansas.

Arizona, Nevada and California have begun implementing a drought contingency plan that requires them to contribute water to Lake Mead to prevent elevations from reaching shortage conditions. Moody's Investors Service on Tuesday called the move a credit positive for those states' water and power utility providers.

“Resiliency now is not just a word; it’s obviously something that people are prepared to do,” Rubin added.

“The real problems are, it’s still one of those areas where people don’t want to invest money, necessarily, because they’re not clear as to what the return is. And, they don’t really want to take the time to look at the grants that are being made.”

Municipal market defaults are rare and have not occurred after natural disasters, Bank of America Merrill Lynch pointed out. Still, said the bank, hurricanes can pressure weaker credits.

“The extent and speed of recovery is often dictated by a municipal issuer's credit pre-storm,” said BAML Merrill. “The focus here, at least in the short-term, is on liquidity and reserve levels.”

Post-disaster scenarios involve “cooperative federalism,” said BAML Merrill. “Even in the most extreme scenarios, the credit impact on both state and local governments from natural disasters is largely muted by reimbursement of repair and rebuilding costs from the federal government, mostly through FEMA and [Housing and Urban Development].”

Private insurance also offsets disaster impact.

Underscoring the rating agency buildout in climate surveillance is the purchase two months ago by Moody’s Investors Service of a majority stake in

These include heat stress, water stress, extreme precipitation, hurricanes and typhoons and sea level rise.

According to Rubin, states and municipalities need to budget soundly before disasters strike.

“You can call them liquidity, you can call them rainy-day funds, you can call them whatever you want, but you should be bonding for that, and part of your normal bond process should have funding available to be able to do that,” he said.

For example, said Rubin, a $250 million bond to build a bridge could be $300 million instead, baking in $50 million for resiliency and “making sure that if something should happen to that bridge, you will have the money available to be able to do it.”

New York City is hosting

Separately, London-based Climate Bonds Initiative on Tuesday released the Climate Resilience Principles, a guidance for governments, investors and banks to determine when projects and assets are compatible with a climate resilient economy. Climate Bonds Initiative, World Resources Institute and Climate Resource Consulting developed the principles in conjunction with more than 30 specialists who are resilience authorities, drawn from academia, not-for-profit, public and private sectors of climate science.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, separate from the $20 billion protection plan, announced in March a $10 billion Lower Manhattan

“The security of Lower Manhattan should be a national priority," he said at the time.

Flooding from Hurricane Sandy devastated Lower Manhattan in particular when it struck in 2012, killing at least 43 New Yorkers.

A

The study, published in the journal GeoHealth, said Americans endured more than $10 billion in health costs from 10 climate-sensitive events in 2012. That toll may have risen in recent years with the increasing impacts from climate change.

Hurricane Sandy in New York and New Jersey led to 273 premature deaths there, according to the study, and in other states, 6,602 hospital admissions and $3.1 billion in total health costs.

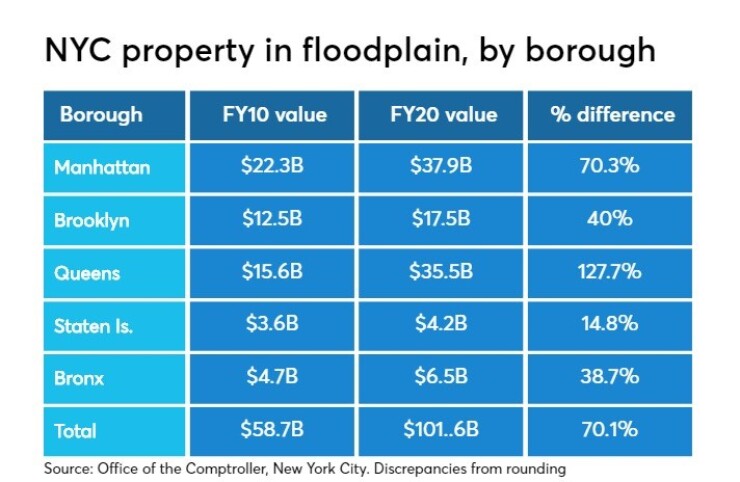

Outer-borough growth in New York has prompted calls for similar resilience citywide. Council members

They filed amid dire warnings from the New York City Panel on Climate Change, which said coastal parts of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx are most at risk of flooding. An estimated 500,000 New Yorkers live near shoreline and sea levels are on pace to climb one foot by 2050.

“Sandy marched onto our shores more than six years ago, caused more than $19 billion in damages, and yet we are ill equipped for when the next storm rolls around,” said Constantinides, who on Tuesday announced his candidacy for Queens borough president.

According to a

The state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s subway and bus system, two commuter rail lines and several intraborough bridges and tunnels, has included measures to enhance environmental sustainability and resiliency in its proposed $51.1 billion capital program, on which its board will vote within days.

The MTA has sold catastrophe bonds in 2013 and 2017 for $200 million and $125 million, respectively.

Meanwhile, the office of the MTA’s new inspector general,

“It’s a very important issue,” she said at a recent meeting of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA. “We need to keep the drains clean because water is dangerous. It’s bad for equipment, it can spark fires and lead to delays and even worse.”

A report by Pokorny’s predecessor in 2006 that said clogged drains led to station flooding have largely fallen on deaf ears, according to Pokorny.

“Keeping drains cleaned is absolutely vital,” she said.