Despite regulations requiring rating agencies to adopt procedures to weigh default risk in a way that is consistent across all types of obligations, numbers show that there remains a wide disparity between the rates of default for same-rated municipal and corporate bonds.

In 2018, B-rated municipal bonds had a zero default rate, while same-rated corporate bonds had a default rate of 0.55, according to S&P Global data.

Post Dodd-Frank

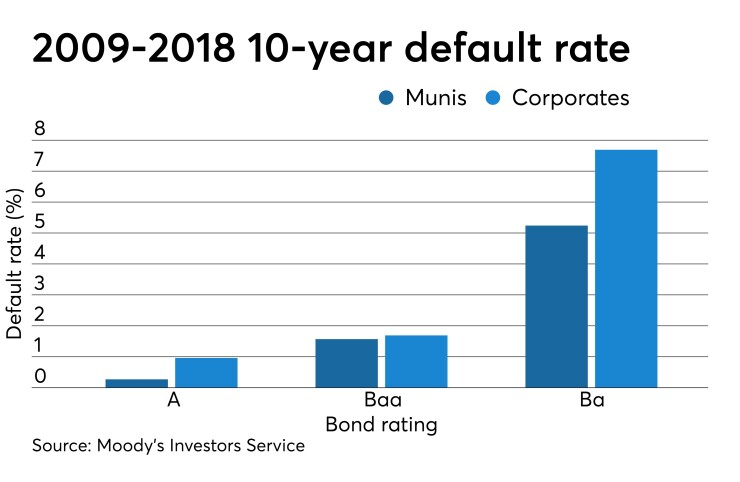

From 2009 to 2018, the 10-year default rate for double-A-rated corporate bonds was 0.63% while same-rated municipal bonds had a 10-year default rate of 0.04%, according to Moody’s Investor Service.

That means double-A rated corporate bonds were almost 15 times more likely to default than same-rated municipal bonds.

Some in the muni market are concerned about the disparity.

“It doesn’t look like there is parity, they may have done some work on making adjustments, but it still appears that there is more wood to chop,” said Ben Watkins, director of the Florida Division of Bond Finance.

Watkins said he was surprised by the Moody’s data showing municipal and corporate default rates.

“I’m surprised by the magnitude of the difference, but then again, on the other hand, my world is the muni world so it doesn’t surprise me that we’re underappreciated,” Watkins said. “Underappreciated in the sense that I just think fundamentally municipals are over the long term are a much safer investment than their corporate counterparts with a similar rating.”

Corporations tend to be more vulnerable to changes, such as in leadership, than governments are, Watkins added and said there was not a justification for there to be a difference in default rates.

According to Fitch Ratings numbers from Jan. 1, 2019, to June 30, 2019, triple-B corporate bonds’ default rate was 0.16, while same-rated municipal bonds had a zero percent rate of default.

This year, from Jan. 1, 2019, to June 30, investment-grade municipal bonds had a zero percent rate of default. In the same time frame, investment-grade corporate bonds had a 0.09% default rate, according to Fitch.

In a Fitch report, from 1999 to 2018, 10-year investment-grade municipal bonds on average defaulted at 0.14%. From 1990 to 2018, the 10-year default rate for investment grade global corporate finance bonds was 1.85%, almost 13 times more than their muni counterparts.

Fitch pointed out that investment grade stats are not an apples-to-apples comparison between munis and corporates because there are more very highly-rated munis on the market than there are corporates.

“Public finance ratings in the United States consist of a large number of AAA/AA ratings, whereas there are no corporates rated triple-A, and very few credits rated double-A,” Fitch wrote in a statement. “Accordingly, the investment-grade default rate for the different classes will be different. Fitch complies with all laws and regulations applicable to credit rating agencies.”

There are signs, though, that the agencies have narrowed the gap in recent years.

The 10 year default rate for investment-grade corporate bonds was almost 90 times more than the same rated investment-grade municipal bonds from 1970 to 2000, compared to six times between 2009 to 2018, according to Moody's.

Defaults can happen idiosyncratically, Moody’s analysts said. Moody’s is always adjusting their methodologies and emphasized that they do not tailor their actions to a predetermined outcome. The Moody’s analysts believe their recent ratings are accurate given the difference between corporations and municipalities.

There have been more muni defaults in the last 10 years, Moody's said. In many cases, municipalities will keep paying their bond debts right up until bankruptcy, said Alfred Medioli, Moody’s senior vice president and senior credit officer.

“Only when they really run out of money, unable to keep the street lights on or keep the policemen paid, do they actually say we’re going to now default,” Medioli said. “Unlike corporate, when it completely goes out of business.”

Over any given time period, default rates between corporate and municipal bonds may not match, Moody’s analysts said. They added that munis can ride out recessions with greater ease than some companies.

“The credit challenges are different between the sector and that there are forward looking risks for any given corporate credit are going to be very different compared to munis, “ said David Strungis, Moody’s analyst. “Munis for a variety of reasons have more flexibility to address those.”

“S&P Global Ratings is committed to achieving comparability of ratings across asset classes and geographies,” S&P said in a statement. “To accomplish this, we've calibrated all of our ratings to a common set of stress scenarios and definitions.”

That has resulted in stronger ratings for munis, and muni upgrades have outpaced downgrades for most of the past several years.

“The important thing to keep in mind as far as default statistics is that they’re inherently backward looking,” said Eden Perry, S&P managing director and head of U.S. Public Finance. “So we have seen a steady migration up the rating scale, even through the Great Recession.”

Perry also noted that in public finance, default statistics are not going to capture near misses, and said legislative moves could help municipalities not go into default.

Before the Great Depression, Moody’s was the only credit rating agency that assigned ratings. In 1929, 55% of all municipals rated by Moody’s were triple-A. During the depression, over 4,000 municipal bonds defaulted. By 1939, only 1% of bonds were triple-A rated.

After the recession in the late 2000s, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act which included a provision to require nationally recognized statistical rating organizations that the SEC oversees to consistently apply the same symbols to rate municipal and other types of debt.

Out of that came

Rating agencies also have to maintain policies and procedures designed to assess the probability that an issuer will default. In 2010, Moody’s moved to

When Congress enacted the provision, they noticed a mismatch by rating category between municipal and corporates’ default rates, a municipal lobbyist said.

Back then, rating agencies said since municipal credits were better than corporate credits, that if they used the same scale as they do for corporates, all municipalities would get a big upgrade, the lobbyist said. The market would then be crowded in the double and triple-A markets, making it hard for investors to distinguish between the ratings.

“Their explanation at the time was, we need a different rating scale for municipals so that you can see the distinctions in credit more clearly,” the lobbyist said.

Marc Joffe, Reason Foundation senior policy analyst, said he doesn’t take issue with rating agencies looking at different factors in asset classes, but takes issue with how they determine double or triple-A ratings.

“They should be calibrating that so that the default rates are consistent across asset classes and ratings,” Joffe said. “It doesn’t seem to me that they’ve done an effective job of that at all.”

Some believe that rating agencies have improved consistency within municipal credits.

Following the Dodd-Frank Act, Watkins says that among municipal securities, rating agencies have made progress and that ratings are consistent.

Rating agencies have been more transparent about their methodologies, Watkins said now they can see “behind the curtain” to understand how and why municipal credits are changed.

“There’s much more thoughtful uniformity in the way they’re treating similar municipal credits,” Watkins said. “I think there’s been a tremendous improvement in that area, but the recalibration issue, they obviously missed the mark on that.”

Jonas Biery, business services manager for the city of Portland, Oregon, Bureau of Environmental Services, also noticed that rating agencies were more transparent post Dodd-Frank. He has noticed more robust conversations and overall more upgrades for general municipal bonds over the last couple of years.

Biery noted that the discrepancy between default rates for same rated corporate and municipal bonds has gone on for a long time.

“It’s never made a lot of sense to me if you look at just that data point given the extremely low rate of muni defaults,” Biery said. “There are certainly some high profile ones that have been in the news. But those are not indicative of the sector overall.”

The shift throughout the years in default rates suggests some intentional movement to better align corporate and muni ratings, Biery said.

“If default risk is the sole thing a rating measures, then the data would suggest there is still work to do,” Biery said. “I’m of the mind that credit ratings measure a more nuanced reality, in which case some differential in corporate/muni ratings would make sense.”

Credit rating agencies have not been following the law, a securities lawyer said.

“They did do some migrations and the disparity is probably less than it was pre-Dodd-Frank, but to say that they are treating municipals fairly now, they still have not achieved that,” the lawyer said.

The lawyer pointed to

An appropriation pledge is a contractual pledge to annually appropriate the needed funds, though it is not a legal guarantee to make the payment if pledged revenues fall short.

Moody’s downgraded the county to junk status after county commissioners indicated they wouldn’t honor their pledge to repay lease appropriation bonds. The bonds were used in 2007 to build a parking garage, which was supposed to be paid back through a dedicated 1% sales tax. Some believed it was wrong to penalize the county's GO rating, though many analysts agreed it made sense to do so.

“That (downgrade) is a very clear violation of this provision of the Dodd-Frank Act because they downgraded credits where the municipality doesn’t even have the ability to refuse and pay the same way they do on an appropriation credit,” the securities lawyer said.

Moody’s declined to comment on the lawyer’s accusation.

Though rating agencies might be doing a better job than they have in the past, there is still a significant disparity between corporates and municipalities, the lawyer said.

“If you have that kind of obvious statistical imbalance, why is the SEC not bringing a case in this area?” they said.

The SEC's Division of Enforcement hasn't ignored rating agencies entirely.

The SEC brought

Moody’s agreed to pay $16.25 million in penalties, while neither admitting nor denying those charges.