Mayor Bill de Blasio’s proposed record-high $95.8 billion, 10-year capital strategy has prompted calls from some elected officials and budget watchdogs for the city to execute its capital projects more efficiently.

Urging the city to get more bang out of its capital dollars, they have chided officials for what they say is poor coordination among agencies, misalignment of planned commitments, scant accountability in project delivery, ineffective budgeting and clunky, outdated procurement procedures.

“The results? Outrageous cost overruns and absurdly long delays,” City Council member Brad Lander from Brooklyn said during a May 25 budget committee meeting at City Hall.

“I’ve been saying this through previous administrations. It’s not the fault of the de Blasio administration.”

Lander and several other council members, including finance committee chairwoman Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, have proposed city legislation to overhaul the system.

Their “issue brief” -- based on an analysis of the

“On average, they are $30 million over budget and 700 days late,” said Lander.

According to Lander, limiting the dashboard to budgets above $25 million omits most of the projects under way in neighborhoods. Delays and cost spikes to many smaller undertakings add up, he said. “Bringing all projects together in one system will help policymakers better understand common challenges and best practices," he said.

Their recommendations include expanding the dashboard beyond the $25 million threshold; establishing a capital projects management task force; overhauling the project evaluation process; expanding the scope of the city’s asset information management system and expanding the Department of Parks and Recreation’s web-based capital projects tracker.

Critics say that capital projects often feature absurdly front-ended timelines with unwieldy design elements, and off-mark assumptions about low commitments in the later years of the plan.

The Center for an Urban Future's

Co-authoring the report were Jonathan Bowles and Eli Dvorkin, the center’s executive director and managing editor, respectively; and Maria Doulis, a vice president and director of city studies for the watchdog Citizens Budget Commission.

Routine maintenance projects take years to finish, the report said.

“As one example of how seemingly simple projects can get bogged down in different stages of the process, a group of fire-safety projects at the New York Public Library took only three months to build and install but spent 1,499 days in the planning and approval phases before construction could even begin.”

The city's size and complexity make managing capital projects more difficult, said Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management.

“If you look at the infrastructure needs of the city, generally, there are so many multiple agencies for the city to deal with. That makes it complicated to work through a capital program.

“The city has been so successful economically that the infrastructure can’t hold a large number of people. It’s a dense city and you have to build around many existing operations.”

De Blasio’s budget director, Dean Fuleihan, said the capital strategy “keeps infrastructure in a state of good repair, promotes health and safety, and expands access to education and opportunity.”

He told council members: “You’ve articulated some very thoughtful concerns. Do we need to be making improvements? Yes.”

The Citizens Budget Commission also cited the need for improvement.

“Realistic timing refers not only to the early years of the capital plan, but also to the latter years of the capital strategy, which appear underfunded,” CBC said in a

“Funding trails off or is zeroed out for important infrastructure types.”

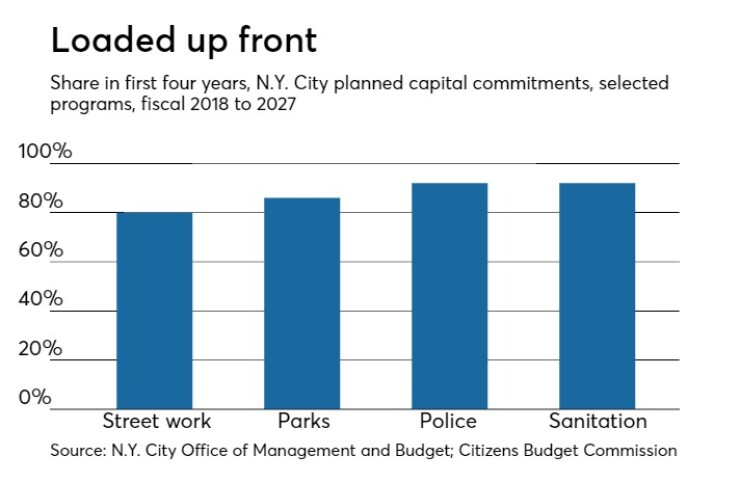

For example, said CBC, the share of planned 10-year capital spending in the first four years of the plan is 80% for street reconstruction; 86% for parks, playground and recreational facilities; 92% for police facilities; and 92% for sanitation garages and facilities.

“Furthermore, the capital planning process should include a better assessment of capital needs — including the resources needed to bring city infrastructure to a state of good repair — and metrics to assess performance,” CBC added.

CBS also said the asset information management system, which reports on the condition of city assets and needed investment to attain a state of good repair, is too superficial, and that the capital plan overall “lacks programmatic indicators” to measure progress.

“When you look at the big items in the city’s capital program, you have education, water and sewer, transportation and housing,” said Evercore's Cure.

“Housing has gotten more attention, but compounding it is that it’s dependent on federal money and I’m not sure you can count on that. There’s been a squeeze in funding but there are prospects for even more cuts.”

One option, according to Cure, is for the city to privatize some of its rental units to the private sector through a Department of Housing and Urban Development program, but it raises the question of whether the city would cede control.

The inability to execute design-build project delivery is also tying the city’s hands.

De Blasio, Fuleihan and city transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg all say the city can save millions and have pushed state lawmakers in Albany for enabling legislation.

Yet design-build only exists for selected state projects such as the Tappan Zee and Goethals bridges and friction between de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo doesn’t help the situation.

“I’m not sure if the state wants to give it up. Then you have the relationship between the governor and the mayor,” said Cure.

Other variables include climate change priorities following Hurricane Sandy. That includes the decision by the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority to close the Canarsie tunnel, which carries the L subway line between Manhattan and Brooklyn, to repair damage from Sandy.

The move will create a large ripple effect on other transportation modes, including those city-run.

Capital spending is much more in focus now, said Cure.

“It’s getting more attention. Finally we’re having a national debate about infrastructure. It was discussed throughout the presidential campaigns.”