The $900 million in reserves that help support Chicago's bond ratings are on the radar of city council members as the city stares down a huge budget gap.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot has left all “options on the table” to deal with the $1.2 billion hole in the city's 2021 budget.

She has signaled that layoffs and higher property tax at the back of the list of options to be used to balance the budget she will unveil next month.

Lightfoot’s chief financial officer, Jennie Huang Bennett, also left one-time practices like scoop-and-toss refinancing on the table, although she said the city was not considering asset leases and has put the use of reserves at the bottom of the list of potential options.

“What purpose do reserves serve if we don't utilize them in times when you have a problem?” Alderman Jason Ervin asked Bennett Friday during the second of a pair of online Finance Committee hearings held to look at the city's revenue options.

Council members want to avoid painful service cuts or tax hikes to close the gap.

Ervin equated the situation to a tenant facing eviction who can’t access their own money in bank accounts. “Why wouldn’t we try to use those reserves to try to smooth things out?” he said.

Ervin proposed a short-term borrowing from the reserves with a dedicated repayment plan in lieu of austere cuts or potential tax hikes which are a “hard sale….when you are sitting on a billion dollars.”

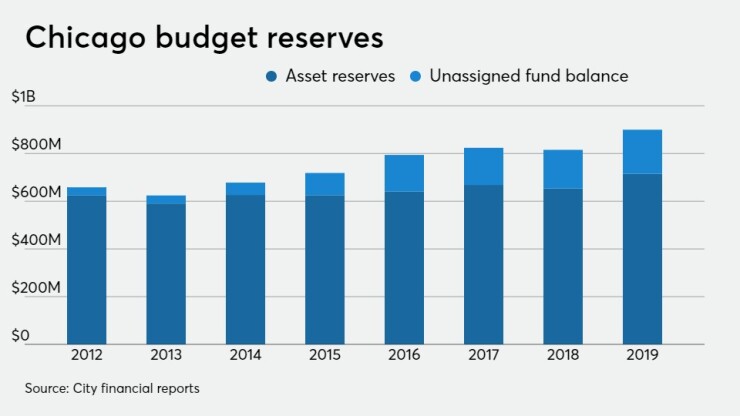

The city holds about $715 million in a long-term asset reserve account and $189 million from the unassigned 2019 fund balance.

Bennett cautioned that the city has already incorporated a recovery into longer term revenue projections, which leave it hard-pressed to find revenue to repay the reserves. The city would need such a repayment plan to avoid rating downgrades, she said.

“The reason why the rating agencies, I think, have given us some forbearance at this point on our credit is because we have those reserves to cover us,” Bennett said.

The city’s GO bonds are rated BBB-minus by Fitch Ratings, A by Kroll Bond Rating Agency, junk-level Ba1 by Moody’s Investors Service, and BBB-plus by Standard & Poor's Global Ratings. S&P assigns a negative outlook; the others assign a stable outlook.

If the reserves are drawn on now, the city would have little buffer to cope with the challenges posed by a potentially delayed economic recovery. “It may be raining now but it could also be pouring,” Bennett said.

The city set up its first formal reserve with a portion of the $1.83 billion of proceeds from its 2005 99-year lease of the Chicago Skyway toll bridge. It bolstered the reserves with $400 million from its $1.15 billion concession in 2009 of the parking meter system.

Former Mayor Richard Daley drained most of the parking meter reserves to avoid cuts or tax hikes in his last few budgets during the Great Recession. Daley did not seek re-election in 2011. Daley’s successor Rahm Emanuel reserved the trend and began making small deposits of roughly $5 million to $15 million annually back into reserves or a liquidity fund.

The city’s fund balance also has grown in recent years from a low of $33 million in 2012 to $184.6 million in 2019.

Bennett also attempted to tamp down enthusiasm among aldermen for too heavy of a reliance on deficit borrowing or the use of pension obligation borrowing for budget relief. Bennett has said the

The city must tread cautiously, limiting one-time measures to the one-time wounds experienced due to revenue losses from the pandemic.

The pandemic’s revenue hit is behind the $800 million gap for 2020. It’s being closed with $100 million in interest savings from the city’s January refinancing, $100 million from an upcoming refunding for upfront savings, $350 million in CARES Act funds that can offset costs, other spending efficiencies, and a hiring slowdown. Bennett said during the hearing there’s also an ability to include a portion in additional borrowing under consideration.

“It’s about a broader finance plan and how it is we tell the story about one-time use versus structural use and what our plan for structural balance is in the out years,” Bennett said.

The $1.2 billion 2021 gap is due to the one-time $873 million toll of the pandemic on revenues while $421 million is due to rising structural costs for debt, pensions, personnel, and other expenses. The city is operating this year on a $4.4 billion general fund.

Alderman Leslie Hairston wants Bennett to consider some form of grant anticipation note between $100 million and $500 million based on future revenues.

Bennett has not put a dollar amount on what’s under consideration and said recently the city could use the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility or might go forward to borrow in the market.

When you are borrowing against a future revenue stream you will need to come up an alternative way to cover future costs that were to be covered by those redirected funds, Carol Portman, president of the Illinois Taxpayers Federation, warned aldermen.

“It's the scoop-and-toss, kick-the-can down the road kind of thing” that may be appropriate to consider due to the pandemic but has pitfalls, Portman said. “There are no good answers here. There's no magic silver bullet."

Aldermen quizzed Ralph Matire, executive director for the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, on pension borrowing. The group has laid out some options for “restructuring” the pension debt including one he said would trim $4 billion off the city’s costs and improve funding ratios more quickly through a series of borrowings.

“I just want to caution it's not a budget gap closing tool unless you can demonstrate that you are generating real savings in the long term for the city of Chicago,” Bennett said. "A POB in and of itself doesn't generate budgetary relief...if you are generating significant amounts of budgetary relief then you are in essence layering in scoop and toss into a POB.”

When the city has discussed POBs in the past with rating agencies “it's not been a good outcome and I warn those who think that somehow it's a silver bullet” that the city would face other ramifications.

Bennett also warned that with city taxable rates around 6% and the assumed investment returns at between 6.75% and 7.25% there’s little room for arbitrage benefits.

The city can’t cut benefits due to state constitutional protections for pensioners. It could take other actions, like the state has done, in offering a pension buyout but the potential impact is limited. The state is also considering funneling asset sales to its pension system.

The city’s pension contribution rises to $1.81 billion in 2021 from $1.68 billion and is carrying

About 16% or $690 million of Chicago's corporate fund comes from sales tax but the city’s rate when combined with the state’s share and Cook County is one of the highest in the country. Income taxes from the state’s local government distributive fund account for 6% or $270 million and personal property lease taxes account for 8% or $350 million. Property taxes totaling $1.5 billion repay debt and pensions.

Lightfoot will propose raising the personal property cloud lease tax to 9% from 7.2% to bring it in line with other lease-related taxes.

Bennett highlighted that, while Emanuel phased in a $550 million property tax levy increase, tax rates have been offset by new property that has been added to rolls. Some aldermen said Bennett’s comments suggest a hike is in the works, but she said that decision has not been made.

Fiscal and policy experts testifying during the hearing called for the state to expand the sales tax to cover services which could generate hundreds of millions more for the city annually.

The city is exploring requesting payments-in-lieu-of taxes from large not-for-profits that don’t pay property taxes.

PFM Group’s Randy Bauer, a director in the management and budget consulting arm, cautioned that such PILOT payments are not required. "You are not going to collect exactly what you are asking,” Bauer said citing Boston’s experience.

The city also will continue lobbying for a restoration of the full 10% allocation of state income taxes. The state had cut the LGDF level down to between 6% and 7%.