WASHINGTON — The Great Recession significantly widened states’ pension and retiree health care funding shortfalls, the Pew Center on the States concluded

Overall, the gap between the promises states made for employees’ retirement benefits and the money they set aside to pay for them grew to at least $1.26 trillion in fiscal 2009, a 26% gain in one year, according to the report.

“As we pointed out last year, the states dug themselves into a big hole before the Great Recession ever hit,” Susan Urahn, the center’s managing director, told reporters during a telephone briefing. The recession worsened the situation by sparking severe budget shortfalls and dramatic declines in investment returns for states, many of which reduced or stopped making payments to their benefit plans, she said.

Pension plans accounted for more than half of the overall gap, as states put away only $2.28 trillion to cover $2.94 trillion in long-term liabilities, leaving a difference of about $660 billion, the report found. Retiree health care and other benefits represented the remaining $604 billion, with state assets of only $31 billion falling far below the $635 billion of liabilities.

The growing pension funding gaps are manageable if states are disciplined about making annual contributions to their plans and if they structure their pension benefit plans to ensure they will be able to manage the long-term liabilities, Urahn said.

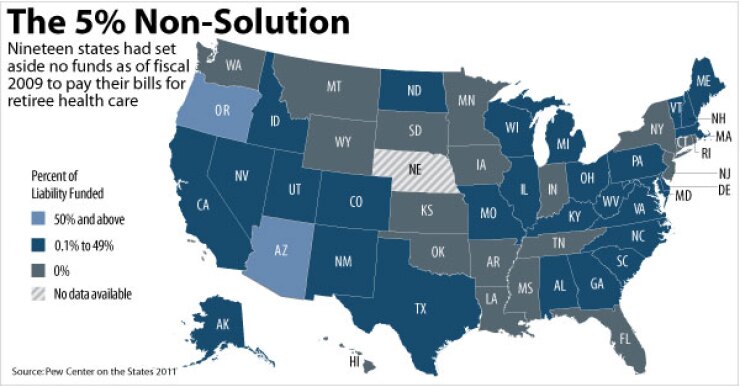

However, retiree health care and other benefit programs have “the potential to be problematic over the next decade,” particularly in states with no assets to cover these costs that are faced with soaring health care costs and the impending retirement of baby boomers, she said. “In those cases, [states] may well want to think about putting money aside and dealing with it much more like pensions, but it will depend on the state.”

At least 19 states have nothing saved and use annual revenues to pay for retiree health care costs on a pay-as-you-go basis, Urahn said.

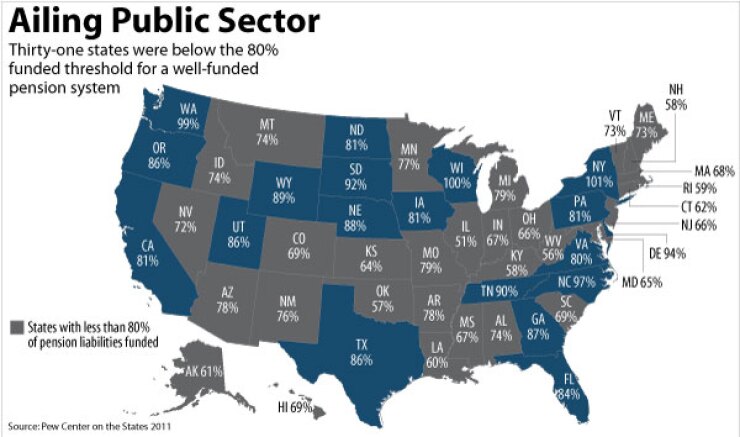

State pension systems, overall, were funded at slightly less than 78% — a decline of six percentage points from the 2008 level of 84%, the report found. New York had the highest funding level at 101% followed by Wisconsin at 100%, while Illinois, at 51%, and West Virginia, at 56%, were at the back of the pack.

Most experts contend states’ pension funding levels should be at least 80%. The Pew Center found 31 one states were below this level at the end of fiscal 2009, compared to a year earlier when only 22 states were below 80%.

New York and New Jersey illustrate the importance of states making annual contributions to their pension systems, Urahn said. Both states had fully funded pension plans in 2002. New York continued to pay its annual bill in full. But New Jersey officials failed to make more than 60% of their annual contributions so that the state’s unfunded liability grew by $46 billion. Today, New York’s pension liability is almost $147 billion, compared to New Jersey’s, which is almost $135 billion. But New York’s required annual contribution is $1.6 billion less than New Jersey’s, she said.

New York and Arizona, both under severe fiscal stress, are mandated by state law to make full annual pension contributions, but most other states have no such requirement, Urahn said.

The report takes no position on the discount rate a state should use to determine its unfunded pension liabilities and annual contributions. Most states assume 8% average rates of return on their investments. The Pew study shows the median investment return was 9.3% for the past three decades, from 1984 to 2009, and was 8.1% for the past two decades, from 1990 to 2009. However, from 2000 to 2009, when there were two recessions, the median rate of return was only 3.9%. Some federal lawmakers argue that states should use a riskless rate based on a 30-year Treasury, which was 4.38% as of mid-March, or a corporate bond rate, which was 5.22% as of mid-March. The Treasury rate would cause states’ pension liabilities to grow balloon to $4.6 trillion, of which $2.4 trillion would be unfunded, the report said.

Urahn said five states have lowered their assumed rates on investment returns over the past year: Alaska, from 8.25% to 8.0%; Illinois, from 8.5% to 7.75%; New York, from 8.0% to 7.5%; Pennsylvania, from 8.5% to 8.0%; and Rhode Island, from 8.25% to 7.5%. But the lower rate caused Rhode Island’s unfunded liabilities to rise by almost $1.5 billion or 27% and its annual contribution level to nearly double. “Clearly this is not a simple of a change in accounting method,” she said.

Other states are changing benefits to lower their future liabilities and make them affordable, steps easier to take in the health care area where long-term benefits are less defined and not set in stone. While states can easily set new benefits for new employees, changing the benefits of existing ones and retirees risks litigation.