Property tax assessments across Texas soared as the coronavirus clipped the state economy in 2020, raising political pressure on state and local leaders seeking to maintain tax caps prescribed by the Texas Legislature.

Lawmakers who passed property tax reform legislation in 2019 will reconvene in January amid a pandemic that has disrupted state and local finances. The Texas Legislature meets only in odd-numbered years.

With no state income tax, state government relies heavily on sales tax while local governments depend primarily on property taxes. Some cities, counties and districts add their own sales tax with voter approval.

“Sales tax revenues have declined as a result of the COVID-related economic slowdown,” the Texas Municipal League told its members this month, referring to Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar’s October sales tax report. “Even when Texans are back to work, many city budgets will be upside down, with a greater demand for programs and services than money to pay for them.”

Senate Bill 2, known as the Texas Property Tax Reform and Transparency Act, was signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott on June 12, 2019, creating a new formula for setting property tax rates in a time of rapidly rising values.

The law bars local governments from raising property tax revenues for operations more than 3.5% above the previous year without an election. Previously, the rate could not exceed 8% without triggering a petition for a rollback election. Under the new law, no petition is required. The law does not affect property taxes for debt service.

“There’s been a steep learning curve for city officials on S.B. 2, but cities have risen to the occasion, especially considering the added significance of property taxes during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Texas Municipal League director of legislative services Monty Wynn wrote to legislative leaders on Nov. 13.

A survey of TML members showed that more than half the cities surveyed adopted a tax rate that was less than or equal to the city’s “no-new-revenue rate,” meaning a rate that would keep total revenues the same as in 2019.

Another 40% adopted a rate that was higher than the no-new-revenue rate, but less than or equal to the 3.5% cap.

Less than 5% of the cities surveyed adopted a rate higher than the 3.5% voter-approval rate, but less than the equivalent of an 8% voter approval rate.

“The survey data shows that the vast majority of Texas cities, 92%, did not adopt a tax rate higher than the 3.5% voter-approval tax rate,” Wynn wrote. “In fact, a majority of cities did not increase their rates beyond the no-new-revenue tax rate, meaning that those cities generally did not bring in any additional property tax revenue in 2020 as compared to 2019 for the same properties taxed in both years.”

Property valuations were sent out to homeowners and businesses across Texas before the pandemic hit in March, and many property owners projected their assessments.

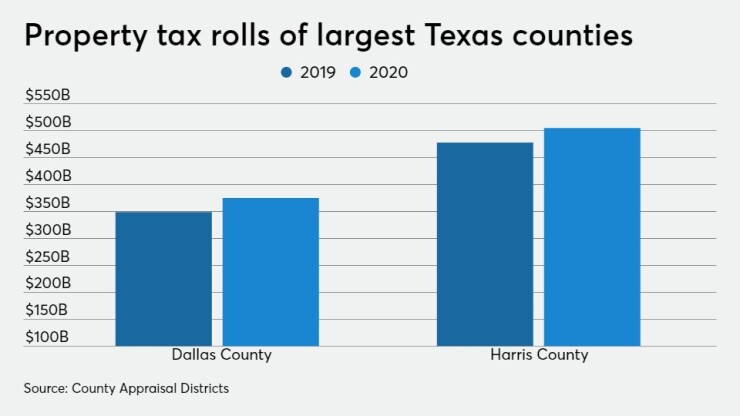

Estimated property values in Dallas County were up 7.5% after protests of assessments. Preliminary property valuation countywide this year is $375 billion, compared with the 2019 certified tax roll of $348.9 billion, according to the Dallas Central Appraisal District. The 7.5% increase amounts to $26.3 million.

The Texas Association of Appraisal Districts asked Abbott in March to request taxpayer relief in the form of rolling values over from the previous year or resetting tax calendar deadlines.

But the request was denied.

The Texas Constitution requires appraisal districts to assess property according to market value. When all properties are appraised and most protests are resolved, the appraisal district certifies the total taxable property value in a given year.

This year, Harris County, the state’s largest, saw a 5.7% increase in value. Single-family homes made up 41% of the county’s tax base, apartments were about 11%, and commercial properties other than apartments made up approximately 26%. The total taxable value of residential properties increased 3% compared with 2019; the taxable value of apartments increased 21% and commercial properties increased 9%.

“The tax rate is actually discretionary, but the appraisal is not,” Jennifer Rabb, director of the McNair Center for Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth at Rice University, told the Texas Senate Committee on Property Tax in February.

The Travis Central Appraisal District announced it would not appraise residential properties this year after the Austin Board of Realtors sent the district a cease-and-desist order in May prohibiting use of its market data in the process.

Without access to this market data, TCAD Chief Appraiser Marya Crigler said her staff is unable to accurately assess residential property values and so the district would use last year’s values again this year.

Nicole Conley, Austin Independent School District chief of business and operations said the school district would need to assess the impact of the decision.

“We greatly understand the need for property tax relief,” Conley said in a prepared statement. “Though we understand why the Austin Board of Realtors has taken such measures, we also realize this could reduce revenue growth for local school districts. It could also potentially shift more funding burden to the state, and create more instability in public education funding.”

Nearly three times more property owners in Travis County have protested their appraisal values than last year, according to the Tarrant County Appraisal District. More than 85% of the protests came from homeowners, with the rest from commercial properties.

Commercial properties have been hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, but most owners and investors will have to wait until 2021 to protest their property appraisals.

Texas economist Ray Perryman, founder of the Perryman Group in Waco, said his November forecast “indicates significant declines in economic activity through 2020, despite a notable comeback from the dark days of spring, but a return to growth next year.”

Perryman’s data indicates that prior peak job levels will likely reoccur in early 2022.

“Texas is projected to retrench a little more than the nation this year, but recover a little faster next year, due in part to the fact that the state's largest export sector (oil and gas) has been hit particularly hard,” he said.

“For Texas' largest metropolitan areas, the decline in employment on a year-over-year basis for 2020 is projected to range from 3.34% in the Dallas-Plano-Irving area to 4.23% in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land area. Recovery in 2021 is expected to be strongest in the Austin-Round Rock-Georgetown, Dallas-Plano-Irving, and San Antonio-New Braunfels areas.”