California Gov. Gavin Newsom's effort to distance himself from his predecessor's priorities sowed confusion about the fate of the state's bond-funded high-speed passenger train project.

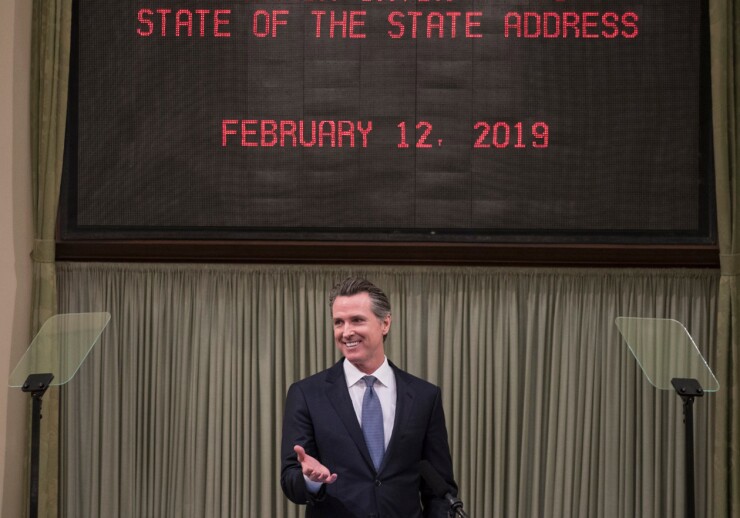

In his first State of the State speech Tuesday, Newsom took aim at high-speed rail and water tunnel projects championed by former Gov. Jerry Brown.

He created confusion about high-speed rail when he said he wanted to prioritize construction on the already underway Bakersfield to Merced segment in the state's Central Valley.

The initial impression was that Newsom planned to scrap the San Francisco and Los Angeles ends of the project to leave the shortened Bakersfield-Merced line.

"The current project, as planned, would cost too much and respectfully take too long,” Newsom said in his speech. “There's been too little oversight and not enough transparency."

Newsom later walked things back a bit, saying he is not scrapping the project, which was launched when voters in 2008 approved a $9.9 billion general obligation bond measure. Newsom said he wants to “get real” about the project, which appears to mean slow-walking the preparations for the San Francisco and Los Angeles ends without formally canceling them.

Estimates have ballooned to $77 billion for the project, now expected to be completed in 2033, several years behind the original projections. Project estimates of $45 million in 2010 included a second phase to Sacramento that is not included in the new, higher tally.

U.S. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, a Bakersfield Republican,

President Trump, already a foil for California's Democratic governor,

That's one reason the full project isn't formally canceled.

“Abandoning high-speed rail entirely means we will have wasted billions of dollars with nothing but broken promises and lawsuits to show for it,” Newsom said. “And by the way, I am not interested in sending $3.5 billion in federal funding that was allocated to this project back to President Donald Trump.”

Under terms of the stimulus grant, If the state doesn’t finish the Central Valley segment by 2022, it forfeits the federal money.

Newsom’s chief of staff Ann O’ Leary

The state

The state has issued $3.3 billion in total to meet the cash flow needs of the project as well as state and local connectivity projects, for which $950 million was designated in the bond measure, said H.D. Palmer, a spokesman for the state Department of Finance.

That leaves $6.6 billion in remaining bond authority. Of the $3.3 billion issued, there is still $2.6 billion outstanding, as $700 million has been paid off, Palmer said.

“The balance of the unissued bonds will still be sold to finish up the Central Valley segment as well as for the bookend projects that were already appropriated,” Palmer said.

Newsom clarified in his own tweets that he had called for setting a priority on getting high-speed rail operating in the only region in which the state has commenced construction, the Central Valley, while affirming a commitment to carry on the environmental work statewide to complete regional projects in the Bay Area and Los Angeles and to pursue additional federal and private funding for future expansion.

Proposition 1A called for the first phase of a statewide system to connect San Francisco and Los Angeles with 220 mph electric trains. A second phase was to extend the routes to Sacramento and San Diego.

“Right now, there simply isn’t a path to get from Sacramento to San Diego,” Newsom said in his speech, “let alone from San Francisco to L.A. I wish there were.”

The authority has secured $12.7 billion in funding and secured and identified up to $15.6 billion in possible future funds for a total of $28 billion, according to

Howle’s audit concluded that the rail authority’s flawed decision making regarding the start of high-speed rail system construction in the Central Valley and its ongoing poor contract management for a wide range of high-value contracts have contributed to billions of dollars in cost overruns. Her audit was requested by the Legislature.

“We are going to hold contractors and consultants accountable to explain how taxpayer dollars are spent — including change orders, cost overruns, even travel expenses,” Newsom said. “It is going online for everyone to see."

Newsom also announced the appointment of Lenny Mendonca, his economic development director, as the new chairman for the rail authority’s board. He replaces Dan Richard, who was appointed by Brown in 2011. Richard submitted his resignation Monday.

If Newsom does shrink the route to only serve the Central Valley, he would most likely would have to return to voters to amend the $9.9 billion bond authorization, said Rudy Salo, a partner at Nixon Peabody.

Salo said he doesn’t think the bonds already issued would be invalid.

The state appropriated $1.1 billion in 2012 to fund “bookend” projects at both ends of the eventual blended system that would provide immediate utility while benefiting the high speed rail system once it was built and attached, Palmer said.

In the north, $600 million will be used for the $1.8 billion electrification of the Caltrain commuter train system on the Peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose. The HSR system will be electric powered and will eventually operate on Caltrain’s existing track. Caltrain’s bookend project will provide much of the electrification infrastructure that the HSR system would need. In the short run, Caltrain will use the electrification to run cleaner, faster, more frequent service.

In the south, the $500 million will be used to fund a subset of a larger set of projects that would be needed for high speed rail to operate.

So far, the state has committed to funding $77 million of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Rosecrans-Marquardt grade separation project for a level crossing that already sees more than 100 freight and passenger trains daily. The rail authority is still working with LA Metro on how best to use the remaining $423 million, Palmer said.

Newsom's water proposal was unambiguous. He withdrew support for Brown's California WaterFix as currently configured, saying he doesn’t support twin water tunnels through the San Joaquin-Sacramento Delta, but said the state can build “on the important work already done” by constructing a single tunnel.

“The status quo is not an option,” Newsom said. “We need to protect our water supply from earthquakes and rising sea levels, preserve delta fisheries, and meet the needs of cities and farms.”

The tunnels would move fresh water around the delta; the goal is to prevent salt water from entering the state system that moves water from the rainier northern regions to agricultural and urban users in the south.

The plan has been debated for decades. It's most recent iteration was reduced to a single tunnel proposal after agricultural districts refused to contribute to the $16.7 billion plan. But the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California reinvigorated the twin-tunnel concept last spring when it offered to pay for the bulk of the project.

“While a single tunnel project will not resolve all pumping problems in the Delta and is less flexible for dealing with climate change impacts, it is imperative that we move forward rapidly on a conveyance project,” said Jeffrey Kightlinger, MWD’s general manager. “Having no Delta fix imperils all of California. We intend to work constructively with the Newsom administration on developing a refined California WaterFix project that addresses the needs of cities, farms and the environment.”