The New Jersey state government's growing fiscal problems may hit the state's localities, public school districts, public universities, and nonprofit hospitals.

The ratings agencies' downgrades of New Jersey to A-plus and A1 this spring have already had a concrete impact on several cities.

Moody's Investors Service dropped the state-enhanced rating of 15 large cities and towns in mid-May to A2, one notch below New Jersey's rating. Among the dropped cities were New Jersey's most populous, Newark, and its third and seventh most populous,, Paterson, and Trenton. Ten of the 15 cities have lower underlying ratings than the New Jersey-enhanced ratings, including these three, so may have to pay higher interest rates when they sell bonds.

State legislators and representatives of Gov. Chris Christie are trying to formulate a fiscal 2015 budget, which must be adopted by July 1. In recent days some Democrats, who control the legislature, have suggested increasing income and corporate taxes. The Republican governor has promised to unveil a state pension plan with lower benefits and thus lower costs.

David Rousseau, who was state treasurer under Christie's Democratic predecessor, Jon Corzine, and now budget and tax analyst for the group New Jersey Policy Perspective, said that the budget outcome will largely hinge on how lawsuits against Christie seeking to overturn his cutbacks to pension funding turn out. Several public worker unions have filed suit against the governor. The suits aim to prevent the planned cutbacks in both this and next fiscal years.

It is not clear whether the court will issue a decision in the suit by June 30, Rousseau said. If there is a ruling against the governor, the judge may not require the state to come up with the additional $884 million it had promised to contribute to the pensions in the final days of the fiscal year. Whatever way the judge rules, the losing side will likely appeal, he said.

There is also an outstanding lawsuit stemming from the 2011 agreement on the pensions reached by the governor and lawmakers. The suit challenges the agreement's suspension of cost of living increases.

If Christie wins these cases, the localities should be able to avoid substantial cuts, Rousseau said. They are unlikely to get increases in the next few years, however.

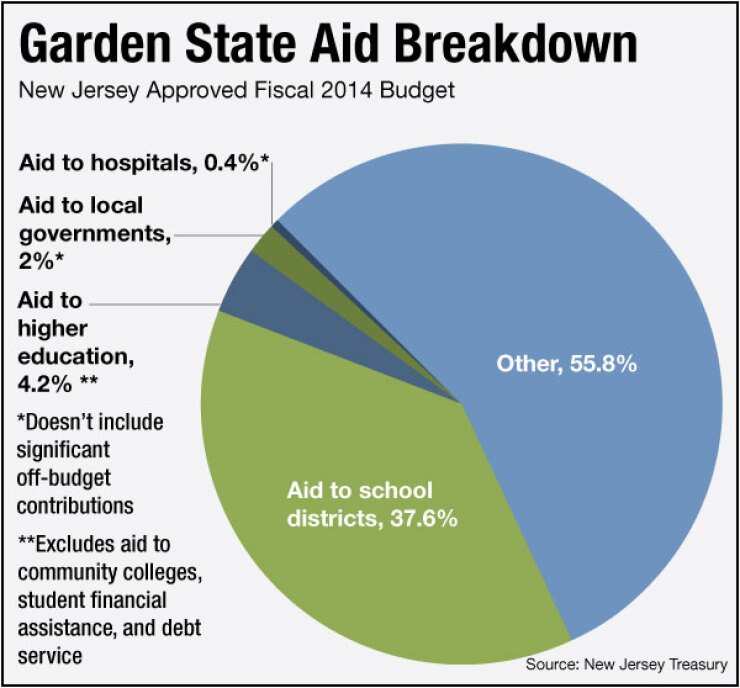

State aid to localities was projected to be 2% of the state's adopted $33 billion fiscal 2014 budget, said New Jersey Treasury director of communications Joseph Perone.

New Jersey State League of Municipalities executive director Bill Dressel said that the localities were probably safe in the short term. The state government certified municipal funding programs in April. It is unlikely that the state would now backtrack on these commitments for fiscal 2015, he said.

However, if the state does not fund its pension obligations in the current fiscal year, they will become even more pressing next fiscal year and this may lead the state to reduce local funding, Dressel said.

In mid-May Janney Capital Markets municipal credit analyst Tom Kozlik said that in seeking a balanced budget, New Jersey state government would cut state aid to the localities.

Moody's dropped Atlantic City, N.J. to Baa2 in November 2013. To deal with its financial issues, the city is seeking state aid. "The state's fiscal situation has certainly not helped Atlantic City," said city director of revenue and finance Michael Stinson. "I would hope investors would look at Atlantic City on its own and not be influenced by issues on the state level."

Even without any cutbacks, the state's localities are already struggling financially, Dressel said. They can rely solely on property taxes and not income or sales taxes. Real estate values have plummeted in the state. The state continues to have among the highest foreclosure rates in the nation, he said.

Up until 1999 municipalities levied an energy tax on electrical utilities that had infrastructure within their borders. In 1999 the state took over the tax, promising to distribute the revenues to the localities. Over the years New Jersey has diverted some of this revenue for its own purposes, Dressel said.

Since 2011 the localities have been barred from increasing spending by more than 2% a year without voter approval. Meanwhile, the localities' healthcare, pension, and insurance costs have been going up faster than 2% annually, Dressel said.

School districts have even more at stake in the state budget. The districts were allotted 37.6% of the budget in the current fiscal year, Perone said. Christie's decision to not provide the promised pension funding would reduce this percentage slightly, if implemented.

The ratings agency downgrades have already affected public school districts issuing bonds. Standard & Poor's dropped its rating of the New Jersey Support of Public School Program to A-plus when it dropped the state's general obligation ration to the same level, affecting 92 school districts. When it put the state on credit watch in early June for a further downgrade it put the enhancement program's rating on watch also, affecting eight participating boards of education.

Manhattan Institute senior fellow Steve Malanga said he thought the state would probably cut aid to the school districts as part of its efforts to restore budget balance.

The state cannot touch school funding for what is known as the Abbott districts, Rousseau said. The New Jersey Supreme Court has mandated the state provide a certain amount of funding for these districts, which serve high proportions of students from poor families. The Abbott district funding is a large proportion of the funding that the state gives to the school districts, he said.

"Given that Christie and the legislature have underfunded the School Funding Reform Act by over $5 billion since Christie took office, it's quite impossible to imagine how they could take even more money from our public schools," said the New Jersey Education Association's director of communications, Steve Wollmer.

S&P believes there is a possibility that the state may be forced to provide more school aid. "The state has indicated that the methodology used to determine school aid funding levels in fiscal 2014 and 2015 is different from the statutory funding formula, which we believe could become a source of pressure if funding is found to be insufficient," said S&P credit analyst John Sugden.

New Jersey's fiscal problems may ultimately affect the state's public higher education institutions.

The state was planning to use 4.2% of its expenditures this year for its higher education, excluding spending for community colleges, student financial assistance and debt service, Perone said. The actual percent will probably be somewhat lower because of it is planning to not make full pension payments for the schools' employees.

Normally, the state pays the pension and health benefits for these schools' employees, as well as gives direct aid to the schools, Rousseau said.

"The level of state appropriation is always of importance and we hope the governor and legislature will continue to show the support for higher education that they have demonstrated in the last few years," said E.J. Miranda, spokesman for Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

After downgrading New Jersey to A1, Moody's revised the outlook of New Jersey City University's A2 rating to negative from stable. The outlook change was due to "the university's high reliance on the state for operating support in the face of a challenging state funding environment with relatively weaker credit fundamentals to mitigate these risks," Moody's said. "The university's commitment to affordability to serve a price sensitive student body combined with narrower operating cash flow and liquidity than peers constrains NJCU's financial flexibility."

NJCU assistant vice president Ellen Wayman-Gordan said less than 30% of its budget came from the state. The university has a total of $131 million in bond debt outstanding.

Another class of municipal bond issuers that New Jersey's fiscal problems may affect is the state's nonprofit hospitals.

State financial support to the hospitals amounts to 2.9% of the budget if one includes federal funds (though these are not normally included in the budget), Perone said.

New Jersey Hospital Association senior vice president Sean Hopkins said that Christie had prioritized funding the state's hospitals as a governor. Hopkins was hopeful that the fiscal 2015 budget would continue to maintain stable levels of funding for the hospitals.

The state's hospitals are struggling, Hopkins said. The 72 acute care hospitals have an average operating margin of about 3%, less than half the national average margin. In recent years there has been an increasing portion of patients not paying their bills, said NJHA vice president Kerry McKean Kelly.

Moody's health care analyst Sarah Vennekotter said the state's charity care subsidies to the hospitals were in place through June 2015. It is possible the state could make cuts to the program afterwards. However, since the state has expanded Medicaid recently, cuts to the charity care program could be offset by having more poor patients having this insurance.