As cities with legacy transit systems cope with aging infrastructure, overcrowding and capital budget strain, ferry advocates suggest taking to the water as a low-cost alternative.

How to budget, plan and integrate with economic development goals remains a work in progress.

“In the long-term, they have a great deal of staying power,” said John Reilly, a senior partner at law firm Squire Patton Boggs. “In the short term, you have the challenge of working within the restraints of a city budget or a transit budget.”

In July, New York’s new citywide ferry service reached 1 million customers one month ahead of projections, amid growing pains that reflect its surprising popularity. They included long waits, anger from excluded neighborhoods, shutdowns during presidential visits and United Nations sessions, and subcontractor financial problems.

“Aside from a lot of the noise -- some serious, some not -- the big story was how high the ridership was. It shows pent-up demand for more transit,” said Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. “People are willing to stay off the subways if they live along a waterfront and they work within a reasonable distance.”

In Boston -- where unlike in New York, the transit system operates the ferries – advocates see ferries as an opportunity for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority to expand without huge upfront costs.

“There are issues of cost and operating efficiency,” said Pioneer Institute research and policy associate Matthew Blackbourn, who co-authored a

By several measures, according to Pioneer, the ferry is one of the most cost-effective modes at the MBTA, which the past two years has operated under a state-run fiscal

The most recent data available – the 2015 National Transit Database -- showed the fare recovery ratio for ferry service at 68% is the highest of any MBTA service mode. The T ferry likewise has the highest fare revenue per passenger mile and unlinked trip, and has the best on-time performance of any of the authority’s transit options.

“This was really an eye-opener for us,” said Sullivan, the think tank’s research director and former Massachusetts inspector general.

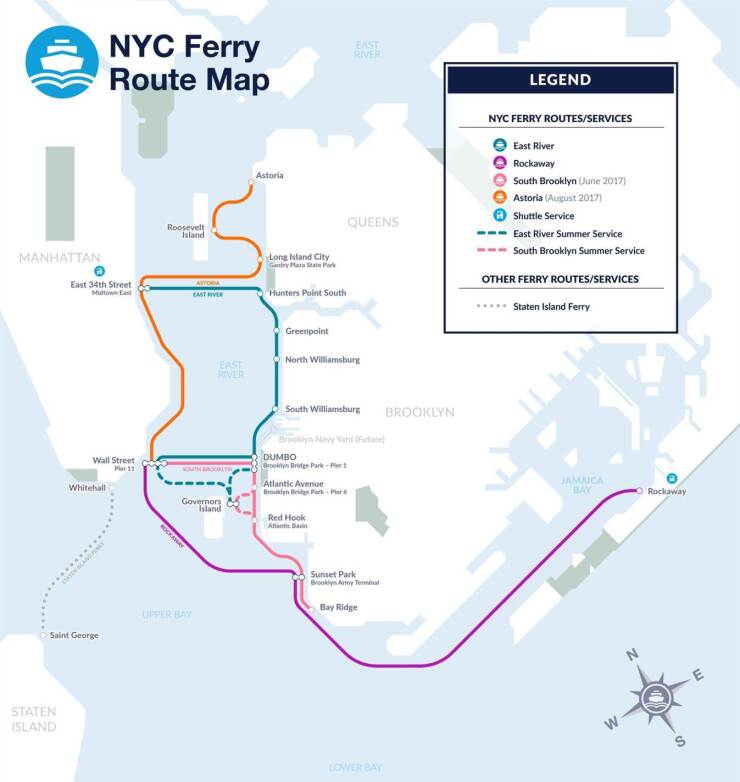

In New York, NYC Ferry launched on May 1. The first two routes were the new Rockaway line, with three stops from the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens to Pier 11/Wall Street in Manhattan and the East River line, with six stops from East 34th Street in Manhattan to Pier 11, with stops in Queens and Brooklyn along the way.

The fare is $2.75 per ride, matching a ride on an MTA subway or bus. The city is providing $30 million in operating support per year, which city officials expect to result in a per-trip subsidy of $6.60.

According to Seth Myers, the executive vice president of the New York City Economic Development Commission, the EDC has allocated $59 million in capital costs for ferry infrastructure including 10 new barges and gangways; $96 million to purchase and upgrade boats; and $41 million to build out its home port at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“The expansion of ferry service would fill a critical need for redundancy in the transportation network, have a positive impact on real estate values and would overall generate wider economic benefits for New York City,” Myers told members of the City Council’s joint committees of transportation, economic development and waterfronts.

The rollout has come with challenges.

Some riders, he said, complained of up to two-hour delays and being turned away completely from riding the ferry due to high demand. United Nations sessions and visits by President Trump have also forced security-related shutdowns.

Subcontractor problems have emerged. Kamcor Inc., which boat operator Hornblower hired to provide welders and other workers to build the ferries, says it has yet to receive full payment for its work on the project. Horizon Shipbuilding, which produced 10 of the ferries at its yard in Alabama, is facing bankruptcy.

Pushback has also come from council members whose districts felt slighted. The city left Staten Island, home to the iconic and free-to-ride Staten Island Ferry but otherwise regarded as a transportation desert, out of the latest expansion.

“A five-borough ferry service that doesn't include five boroughs is sort of an enigma to me,” said Debi Rose, who represents Staten Island and chairs the council’s waterfront committee.

Angry Bronx council member James Vacca asked Myers what metrics EDC used and why such areas in his borough as Throgs Neck and City Island were bypassed.

“I'd be happy to dig ...” said Myers.

“No, no, no,” Vacca interrupted. “You should know now.”

Pioneer – a frequent critic of the MBTA – said its study put aside longstanding political questions about the future of the T and its new governance structure. The commonwealth appointed a fiscal oversight board after a record 110 inches of snow struck Greater Boston in 2015, paralyzed parts of the system and prompted calls for operational overhaul.

“The MBTA has some very big capital challenges,” said Sullivan, citing the authority’s $10 billion state-of-good-repair backlog. “On top of the very heavy debt, when the T looks for ways to address the traffic problem, it’s limited in its capital resources.”

While ferries do not involve rail and tunnel construction, other costs are unique to boat service, according to Squire Patton Boggs’ Reilly.

“You still need safe passengers and specialized labor with navigational skills, and when you have two more rivers and two states, you have jurisdictional matters, and local and regulatory issues,” he said.

Disparate transit agencies – and their political agendas – have long posed operational problems in New York. Gov. Andrew Cuomo is pushing the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s subways, buses, bridges and tunnels plus two commuter rail lines, to streamline procurement and other practices.

The MTA last week approved a $573 million contract to replace the MetroCard fare payment system with a new “tap” card system. How that could integrate with any ferry service is still an open question.

"That would be nice to fix so it could be integrated with the rest of the transit system,” said Gelinas. “It’s challenging enough without using all these payment systems … MetroNorth, Long Island Rail Road, PATH and the ferries ... we would like to have just one card that works with all these things.

“There are ways to pass the money back and forth.”

Reilly sees ferry service as an effective magnet to draw young professionals to New York.

“There is a great cultural aspect. It’s a step toward improving the quality of life for New Yorkers,” he said. “I think that New York has a pretty good story to tell. I’ve got to think that graduates of Stanford, University of Chicago or hundreds of other great schools would welcome robust ferry service. They would not have to live in Manhattan; they could commute from one of the [outer] boroughs.”

While ferry studies have been largely commuter-centric, recreational use is also part of the mix.

“People who use ferries also use them for pleasure,” said Gelinas. “They're easy to discount, but we don't have a lot of opportunities for recreation. Remember, Robert Moses built the [New York] parkways for recreation, for people to get to the countryside.”