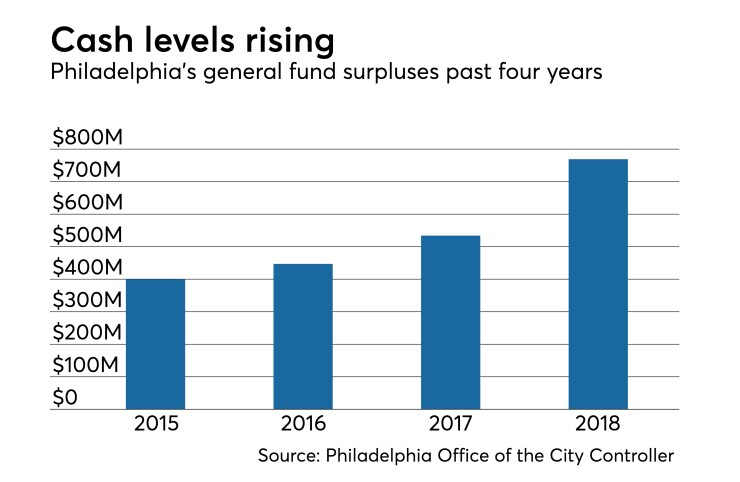

PHILADELPHIA — Philadelphia’s fiscal watchdog says it's time to prepare for the next economic downturn, now that the city's general fund surplus has returned to near pre-recession levels.

Philadelphia City Controller

“We had many years of economic growth and recovery and I think that lends itself to say we should probably put a little bit aside,” Rhynhart said during a chat with Bond Buyer Contributing Editor John Hallacy. “If a Recession hits in a few years, which at some point it will, whether its 2020 or 2021 or whenever it is, it would be much better to be in a position that you had a rainy day fund.”

Philadelphia, which established a rainy day fund policy in 2011, hasn't enacted one in the past few budget cycles because of projections that fund balances would be too small. The city established a fund balance target goal of 6% to 8% of general fund expenditures during its most recent five-year strategic plan with the goal of making deposits into the rainy day fund.

Philadelphia’s final unaudited 2018 fiscal year fund balance ended up at $368 million, which was roughly $140 million higher than what was projected in the city’s five-year budget plan, according to a financial statement released Friday by the administration of Mayor Jim Kenney.

Mike Dunn, a spokesman for the mayor, said the surplus of about 8% of revenues met the city’s fiscal target, though it is below the more than $750 million needed under Government Finance Officers Association recommendations, which say fund balances should equal about two months of general fund revenues.

“While the increased fund balance is a positive development, it also needs to be seen in the context of the City’s larger fiscal position,” said Dunn. “We have also already created reserves in the Five Year Plan for some potential future costs, such as labor contracts and federal funding cuts.”

Dunn said Mayor Kenney plans to discuss with the city council the possibility of creating a rainy day fund as part of the budget process for the 2020 fiscal year. Dunn said the mayor’s administration is examining its options on the City Charter's restriction against mid-term contributions into a rainy day fund.

“A low fund balance is just one of the challenges that rating agencies highlight in discussing the city’s ratings,” said Dunn. “The Administration plans to invest a portion of the additional fund balance in ways that will help the city’s fiscal health.”

Philadelphia has faced budgetary challenges in recent years due largely to a pension system that has $4.4 billion in liabilities and is only 45% funded. Rhynhart said reducing the pension fund’s assumed rate of return to 7.6% from above 9% has helped. She stressed, though, that each 10 basis points drop in the assumed rate of return equates to about a $12 million increase to the city’s general fund payment to the pension plan.

She said ideally the assumed rate of return would be 5%, but that bringing it that low would increase the city’s general fund pension payment between $200 million and $250 million.

“It’s a big challenge and there is no other way to say it other than the city of Philadelphia needs to continue to lower the assumed rate of return and continue to work to try and get changes from the unions and to focus on investment strategies,” said Rhynhart. “It’s a major financial issue, but there is no easy solution unfortunately.”

S&P Global Ratings

Dunn said the Kenney administration plans to tackle the pension challenge by making an additional contribution to the fund that is $22 million more than estimated in the approved five-year plan and $62 million higher than what was included in the 2018 budget. He said the city is also proposing using $30 million into pay-as-you-go capital projects, which may free up flexibility in the 2020 budget because of less need for borrowing.