Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

CHICAGO — The Chicago police pension fund has joined the city firefighters’ fund in seeking to divert state grants to make up for pension payment shortfalls.

The tax levy and collection issue is playing out in the courts. The city argues it doesn’t owe the funds because tax collections fell short.

Chicago joined the short list of municipalities facing the diversion of state-related funds to make up for contribution shortfalls in September, when the Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago firefighters fund

The comptroller began withholding state grants and after a 60-day protest period ended, the comptroller’s office concluded the fund appeared to have a valid claim of $1.78 million and $1.56 million for contributions in 2016 and 2017 and the cash was released to the fund, according to comptroller spokesman Abdon Pallasch.

The Policemen's Annuity and Benefit Fund of Chicago followed late last year,

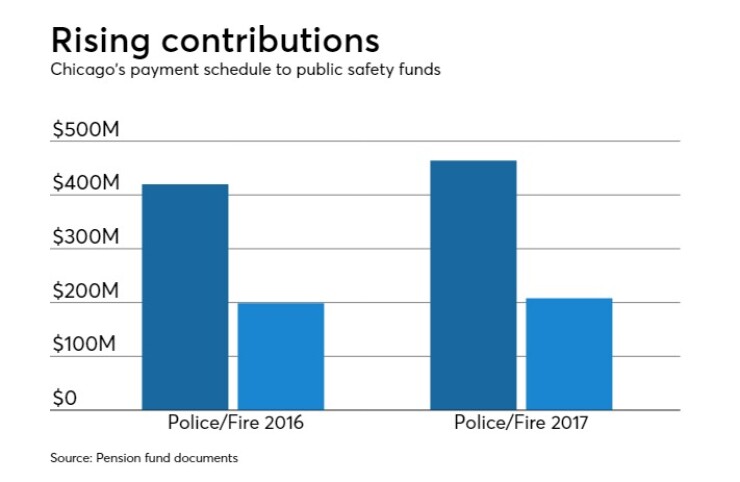

The public safety funds' claims came after the city adopted substantial funding boosts that include significant

The police claim filed with the comptroller notes that it has asked the city to make up the shortfall in the set contribution amount set in statute but that the city believes the difference is “reflective of a loss in collections between the city's tax levies and the actual collections from those levies, and that it is the fund who must absorb said loss in collections.”

“The city continues to maintain and defend its position that it made all statutorily required contributions,” city Law Department spokesman Bill McCaffrey. “If the city prevails in court, it will seek to recoup the state grants diverted to the fund.”

INTERCEPT

The city's contributions to its public safety funds are based on its own set of pension statutes under state legislation that established a set amount that ramps up between 2016 and 2020 to an actuarially required contribution level in 2021.

Previously the contributions were based on a multiplier of employee contributions, a formula that fell far short of an ARC, leading to swelling unfunded liabilities.

Public safety funds and the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, which covers suburban and downstate general employees, fall under a separate set of rules that already requires actuarially based contributions.

The comptroller began enforcing an intercept mechanism of “state funds” such as sales taxes to cover a shortfall in actuarially based payments for the pension systems outside Chicago early last year. Chicago’s pension legislation allows only for the diversion of “state grants.”

Funds from Harvey, North Chicago, and Chicago have triggered intercepts for their public safety funds and a handful of others for IMRF shortages, Pallasch said.

Some researchers and municipal participants feared a flood of requests would follow possibly straining local government budgets as hundreds of public safety funds have reported payment shortfalls. The intercept also has sparked worries that bondholders’ legal claims will fall behind pensioners as distressed governments try to preserve funding for critical services.

LAWSUITS

The city’s police and fire pension overhaul legislation also allows the funds to go to court to “bring a mandamus action in the Circuit Court of Cook County to compel the city to make the required payment, irrespective of other remedies that may be available to the fund,” the state law says.

Last fall, the firefighters fund filed a lawsuit against the city in the Cook County Circuit Court asking the court to declare that the city must make the full payment amount set in statute. A brief status hearing was held last week. Judge Sophia Hall is presiding over the case.

The lawsuit argues that “the plain language” of the city’s pension legislation requires the city “to contribute to the fund an amount equal to $199 million in fiscal year 2016 and an amount equal to $208 million in fiscal year 2017” with the shortfall reflected in the claims filed with the comptroller.

The city has since filed a counterclaim and is seeking to recoup the grants withheld for the firefighters and it is asking the court to find that it has met its obligation that requires it to only levy the amount needed to raise an amount equal to the set contribution, not to actually pay that amount.

“Historically, the city has never added a loss in collection factor to its property tax levy for the fund, and any loss in collection has at all times been absorbed by the fund. There has been no practice of having the city make up for the loss in collection through a supplemental payment to the fund,” the city argues.

The city further contends there was no “intent on the part of the General Assembly to change the settled practice by which the loss in collection is absorbed by the fund and offset by the additional collections that are routinely received after the close of each year.”

City officials had hoped the police fund would hold off on filing its claim with the comptroller until the firefighters' lawsuit was resolved, providing legal direction on the tax collection dispute.

The court’s decision stands to impact future city contribution levels going forward, although it’s unclear what impact it could have on other municipalities, especially those like Harvey where actual property tax collections are weak.

“Should the recapture provisions of the pension code be invoked as a result of the city’s failure to contribute all or a portion of its required contribution, a reduction in state grant money may have a significant adverse impact on the city’s finances,” Chicago wrote in its 2018 annual financial analysis.

The city’s net pension liability stands at $28 billion with the system collectively funded at a 26.5% ratio. The legislative overhaul pushed through by the city is designed to put the funds on a path to a 90% goal by 2055 for public safety and 2058 for muni and laborers.

The spike in contributions at the end of the ramps for all four funds — 2021 for public safety and 2023 for municipal and laborers — will result in a $1 billion increase by 2023 in the roughly $1 billion now paid toward pensions.

How to cover the ARC costs when they hit is the subject of heated debate and a driving factor behind the city’s exploration of a $10 billion pension bond issue. Mayor Rahm Emanuel is not seeking a third term in the February election.