From weather instruments to GPS satellites to the latest polling, technology helps us make decisions based upon what we expect; from what to wear to how long it'll take to arrive at our destination, to who would win if an election were held tomorrow. Closer to home in finance, the analysis of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) involves prepayment assumptions that are used to evaluate both expected principal and interest and ultimately the expected yield of the security. Then why in municipal finance do we consistently focus not on the expected case, but rather the worst case?

The "Worst-case" for Munis

Despite the fact that the vast majority of callable bonds, now often issued with high premium coupons, are refunded long before maturity and even the first call date, fundamental metrics like True Interest Cost (TIC), debt service, and refunding savings are calculated assuming no refunding of the issue ever occurs. This is a worst-case that ignores the significant value of the optional redemption feature that the issuer purchases when bonds are first sold. Chalk it up to appropriate muni conservatism? Perhaps. But when issuers are trying to make informed economic decisions that depends upon good estimates of expected cost of capital — awarding a winner in a competitive sale, fixed versus variable financing, or whether to perform a refunding with callable bonds — aren't issuers making decisions based upon simply incomplete, and dare I say, perfectly inaccurate analysis? To-maturity debt service calculations are admittedly precise, they just happen to be precisely wrong; like the Hubble telescope prior to the fix.

Muni Optional Redemptions — Exotic Options Indeed

The far more likely reason is that realistically modeling muni call features is hard. Most issuers start by looking at refundings on a matched-maturity basis, replacing the existing bond with one of identical maturity. If it's an advance refunding, the issuer also cares about the yield to the call date. This yield is not from the issuer's yield curve; it's the yield for the reinvestment of refunding proceeds, usually SLGS or UST, a related but entirely separate and taxable market! It is this basis, tax-exempt to UST, which is both difficult but also essential to understand and model for advance refundable bonds.

In a way this is even more complicated for the investor. For a pre-refunded bond the investor now holds a security that still has the tax characteristics of the original bond, but is riskless given the escrow backing. And for the investor's valuation, the remaining cash flows should be discounted along the pre-refunded muni curve — yet another yield curve to model. As an aside issuers analyzing the new, though I think destined to be standard, enhanced optional redemption feature also must understand the AAA/pre-re muni curve as it is what drives the economics for that flavor of refunding.

To any trained financial engineer, these types of embedded bond options, whose payoff depends not only on different yield curves shapes but also entirely different markets, would fall squarely in the bucket of exotic options. Compounding this complexity is the inability to short muni bonds; a reality that precludes the muni market from satisfying no-arbitrage conditions.

A Better Solution

Some have advocated on these pages the use of standard bond option pricing models to analyze the muni optional redemption feature. Financial theory and implementation problems aside, option pricing models simply do not work for issuers because they provide no clear way to derive expected bond principal and interest payments, which are the fundamental calculations an issuer really needs to understand. And further, option pricing models are predicated on a refunding decision that is, to put it gently, very different than any refunding criteria actually used in the municipal market (hold value vs exercise value).

Fortunately, recent research has shown ways to create real-world models of multiple, related fixed income markets simultaneously. These models provide the ability to forecast both refunding likelihood and expected savings using the issuer's published or internal refunding guidelines, essentially replicating all the nuance of real refunding decisions. My company licenses calculators that performs these computations both in refunding-adjusted bond structuring software for issuers but also in relative value analytics for investors.

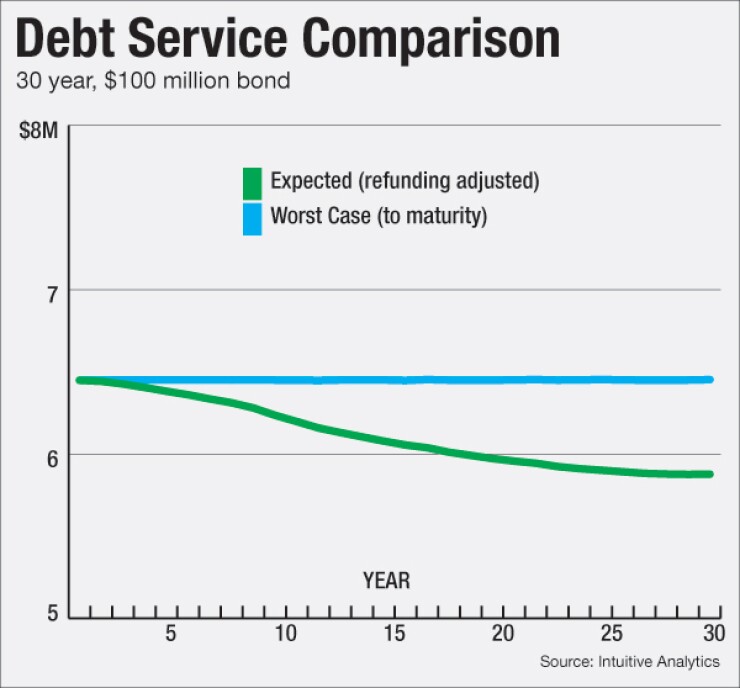

As an example, in the debt-service comparison chart we show worst case (to-maturity) and expected debt service amounts for a new $100mm bond issue amortized over 30 years. Average annual debt service ignoring the call feature is approximately $6.45mm. However, given a real-world issuer refunding policy of 5% PV savings, we see that expected average annual debt service is significantly lower at $6.11mm. In terms of overall issue yield, the worst case (also known as TIC) is 4.316%. However the refunding adjusted (or expected) issue yield is fully 36 basis points lower at 3.961%.

Are those 36 basis points meaningful? Ask an advisor working on a competitive bid where one dealer bids 4 coupons and another 5s. The 5s may well look more expensive on a TIC basis as this reflects no refunding. But look at this on an expected basis, adjusted for refunding activity, and the 5s may be better for the issuer.

That's How We've Always Done It

Worst case, to-maturity debt service calculations that ignore the issuer's optional redemption feature lead to flatly wrong calculations for critical items like expected capital cost, refunding savings, and simple, basic principal and interest payments. Perhaps more so in our modern age, the six most dangerous words in the business lexicon may be "That's how we've always done it." MSRB's new Rule G-42 requires a duty of care stating that a municipal advisor must undertake to reasonably "determine that it is not basing any recommendation on materially inaccurate or incomplete information." Basing any client recommendation on calculations like TIC that ignore the impact of potential future refinancings seems to be doing just that. New regulations coupled with new technology will impact us all. Even in what many consider the sleepy realm of public finance, the times they are a-changin'.

Peter Orr, CFA, is founder and president of Intuitive Analytics.