More than two-thirds of states overestimated their revenue projections in fiscal 2009, forcing lawmakers to reopen budgets for additional rounds of spending cuts, according to a report released Tuesday.

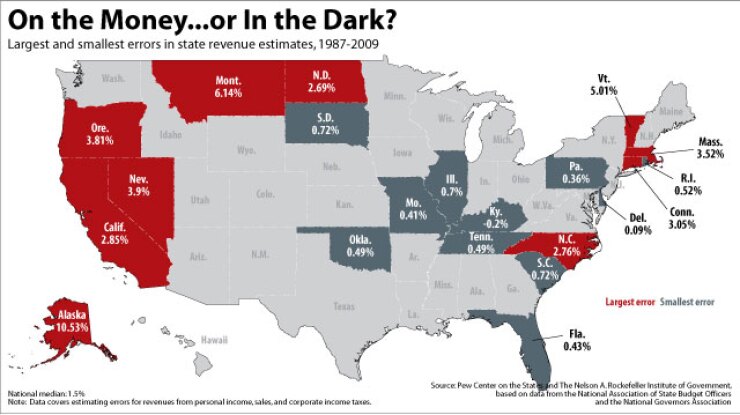

Driven mostly by increasing volatility in state revenue systems, the trend could get worse as states rely more on income taxes for revenue, the Pew Center on the States and the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government concluded in a report, “States’ Revenue Estimating: Cracks in the Crystal Ball.”

States’ overestimated revenues by a combined $49 billion in fiscal 2009, the two groups found. Revenue estimates in Arizona, New Hampshire, Oregon and North Carolina were off by more than 25% for the year.

Budget officials’ revenue forecasts are rarely spot-on, especially during recessions. While private sector economists have it tough enough forecasting the unemployment rate or the stock market, the state revenue estimates need to link economic forces with what the state will actually collect for the year.

But the pattern of overestimating revenues is getting worse, according to the report.

During the early 1990s recession, about 25% of states forecast revenues proved to be too high. By the recession early last decade, that number jumped to 45% — and in fiscal 2009, during the worst of the Great Recession, 70% of all forecasts overestimated revenues by 5% or more.

States are increasingly off the mark because personal income taxes have become a larger segment of tax collections, the report found. Income taxes rely on capital gains taxes, usually profits on equity and housing market sales.

When the meltdown hit, throttling both equity and housing markets, “things went horribly awry” for total state revenue estimates, said Donald Boyd, a senior fellow at the Rockefeller Institute and a co-author of the report.

Getting a revenue estimate as accurate as possible is “a crucial part of the decision-making process” for states because most are required to have balanced budgets, he noted.

In New York, the official revenue estimate for fiscal 2011 was revised lower five times. Its budget gap started at $4.6 billion in July 2009 before almost doubling to $9 billion by March 2010, the report said.

State revenue forecasts could get more accurate in fiscal 2012 as the economy recovers.

“I don’t see missed revenue estimates, particularly on the optimistic side, as a major concern in [fiscal] 2012 and 2013,” said Harley Duncan, managing director at KPMG LLP’s state and local tax practice. “That doesn’t mean revenue growth is going to be robust.”

Credit rating agencies give a wide latitude for revenue estimates, according to Robin Prunty, managing director at Standard & Poor’s.

“State revenues are much more volatile than what you see on the local government side and much more recession sensitive,” she said. Ultimately, a state’s credit rating depends on how it’s able to manage a revenue shortfall.

States expect fiscal 2012 to be the most difficult budget year of the economic downturn. Federal stimulus funds that propped up budgets in fiscal 2010 and 2011 will disappear while revenues recover slowly. Thirty-one states are projecting lower revenues in fiscal 2012 than those collected in fiscal 2008, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Policies.

Fiscal 2012 “will be the most difficult budget for the states,” Prunty said. As states enter the fourth year of the economic downturn, the spending cut choices “just get much more difficult,” she said.