Municipal closed-end funds are fiddling while everyone else burns.

A year-long rally in closed-end funds has been halted in most asset classes by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe and a general distaste for risk that has engulfed most financial markets since early May.

A First Trust Advisors index tracking returns on closed-end funds is down 6.2% since the end of April. Trailing 30-day volatility in the index has almost quadrupled in that time, according to data from Bloomberg LP.

Not so for municipal CEFs. The First Trust index following closed-end funds that invest in state and local government debt is up slightly since the end of April. The sector has delivered total returns of 7.1% this year, after returning 43% last year.

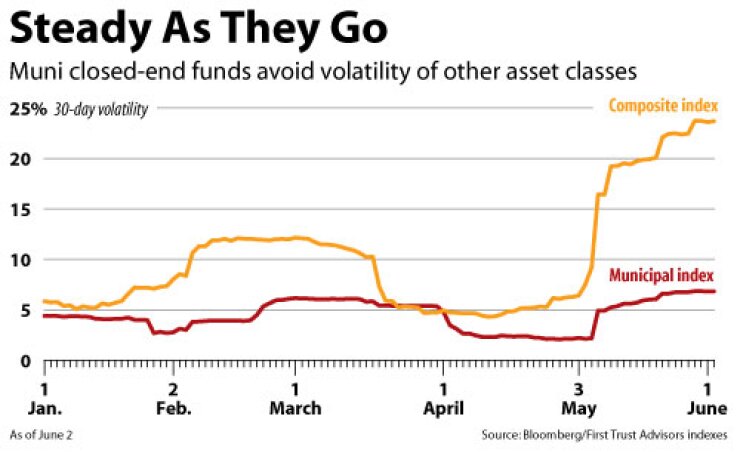

The index has also remained remarkably stable even as volatility in nearly every other market has spiked.

The tax-exempt closed-end fund index’s 30-day volatility — or standard deviation in changes in the index over the past month — is just 6.8%, according to Bloomberg, compared with 23.7% for the composite closed-end fund index. The municipal index was exhibiting higher volatility than the composite index as recently as March.

“European tensions caused the market to experience several rounds of extreme volatility over the past month,” Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors wrote in its monthly report. “Municipal funds ended the period largely unscathed.”

CEFs raise money by selling shares in themselves to the public, then investing that money in an asset, such as bonds.

According to the Investment Company Institute, closed-end funds had $78.56 billion invested in municipals at the end of April.

What primarily distinguishes CEFs from mutual funds or exchange-traded funds is an ability to employ leverage.

Many closed-end funds supplement the cash raised from selling shares by borrowing money and using it to buy more bonds.

Because the yield on the bonds would normally outpace the interest paid on the borrowed money, closed-end funds earn a “spread” that provides additional dividend income to shareholders.

The Nuveen Insured Municipal Opportunity Fund, for example, is the second-biggest component of the First Trust municipal CEF index.

The fund has $1.39 billion in net assets, which are supplemented by $664.8 million in borrowed money.

The fund’s $2.06 billion in total holdings — which include bonds from issuers like the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and the Los Angeles Unified School District — carry an average coupon of 4.84%. The fund’s preferred shares, which provide the leverage, cost the fund only 0.45% in interest.

The additional bonds purchased with the borrowed money therefore juice returns by an amount equal to the yield on the bonds over and above the cost of leverage.

The fund yields 6.12% based on the latest dividend, which Nuveen raised last month.

Stifel Nicolaus analyst Alex Reiss has for months warned investors that municipal closed-end funds do not behave like bond portfolios — they behave like stocks. They trade on exchanges like stocks, they have perpetual maturities like stocks. And when volatility strikes, they tend to sell off like stocks.

Indeed, municipal CEFs have not always been so impervious to volatility.

During the financial crisis in 2008, when the Chicago Board Options Exchange gauge of volatility known as the VIX skyrocketed, muni closed-end funds were demolished. In October and November 2008, the VIX swelled from around 40 to more than 80 in six weeks. During that time, municipal closed-end funds fell 11.6%.

Then when the VIX receded, muni CEFs proceeded on a monster rally.

With volatility reintroduced to the market in the past month, however, municipal closed-end funds have barely shrugged. If anything, they have benefited.

“The whole municipal market seems to be attracting sort of a flight to quality,” said Maury Fertig, chief investment officer at Relative Value Partners.

Fertig attributed the successful resistance against the market’s volatility to investor perceptions that there are tax increases looming, as well as a yield curve that continues to be very favorable for muni closed-end funds.

Because closed-end funds borrow short-term money and invest it in long-term assets, funds benefit most when bond yields are much higher than short-term rates.

The short-term rates that determine what closed-end funds pay for their leverage remain abnormally low. A recent uptick in the three-month London Interbank Offered Rate, to 0.55% from less than 0.3% at the end of March, hardly puts a dent in the nice spread funds are earning from their leverage, Fertig said.

The yield on a 10-year triple-A municipal, according to the Municipal Market Advisors scale, is currently 258 basis points higher than three-month Libor.

While this is a few dozen basis points narrower than the spread over the past year or so, it is still higher than it was virtually every day for the previous five years.

Libor would have to go up several hundred basis points for closed-end funds to lose that advantage over other income products, Fertig said.

Still, with the rest of the CEF universe having sold off and municipals holding firm, Fertig sees the sector as potentially vulnerable.

His firm has about 4% of its assets invested in mun closed-end funds right now — which he says is the lowest proportion ever.

“You really are banking on just the yields continuing to go down and getting some appreciation,” Fertig said. “It’s more of a yield play at this point, and not a deep value play.”

Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors also sees few municipal CEFs worth buying.

Instead, the firm is buying some of the preferred shares funds have sold to serve as their leverage.