Massachusetts transportation officials have spent nearly six years trying to thread a needle and now time is running short.

“The time has come to make a decision, not study alternatives in perpetuity,” state transportation Commissioner Stephanie Pollack said of the Allston Multimodal Project at the June 22 joint meeting of the Department of Transportation and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s Fiscal Management and Control Board.

The project would fix a worn-down swerving viaduct on the Massachusetts Turnpike — Interstate 90 — in Boston's Allston neighborhood.

The headlined and most vexing component is force-fitting a hodgepodge of highway, rail and bicycle and walking paths into a thin stretch of land called the “throat,” which covers only 204 feet between the Boston University property line and the Charles River.

That stretch also includes the at-grade Soldiers Field Road, a parkway along the Boston side of the Charles River. While BU and its namesake bridge abut the area in question, Harvard University lines the Cambridge side across the river.

It stands to be Greater Boston’s biggest megaproject since the controversial Big Dig and its cost is still unknown, although state officials late in 2018 pegged it at $1.1 billion.

The project could start in 2022.

At the throat, the project would need to accommodate five key pieces of transportation infrastructure: I-90, with four travel lanes in each direction; Soldiers Field Road, with two travel lanes each way; the two-track MBTA Worcester Main Line commuter rail; the 82-year-old steel-plate girder Grand Junction Railroad Bridge, which runs under the Boston University Bridge and connects across the river to Cambridge; and the Paul Dudley White bicycle and pedestrian path, modified to separate the two.

"There are only so many ways to rearrange those five," Pollack said.

It is one of the few places in the world where a boat can sail under a train running under a car driven under an airplane.

“The throat is not the project,” Pollack said. “The throat is one piece of a very important and complicated multimodal project, even though we seem to spend much of our time talking about the throat.”

According to Pollack, the project would set out to straighten I-90 west of the throat and open up development land; replace the decaying viaduct; meet MBTA layover and operational needs at its nearby Beacon Park Yards; construct a multimodal MBTA commuter rail West Station to serve the Framingham-Worcester corridor; ease traffic and safety concerns; and improve pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure.

Harvard, which owns about 90 nearby acres on the Boston side, covets the land, with West Station's potential to generate transit-oriented development options. Likewise, pedestrian, bicycle and even rail on the Grand Junction Bridge across the river appeal to Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While MassDOT controls that bridge, MIT owns rights-of-way to a portion of that corridor that runs through its campus in Cambridge.

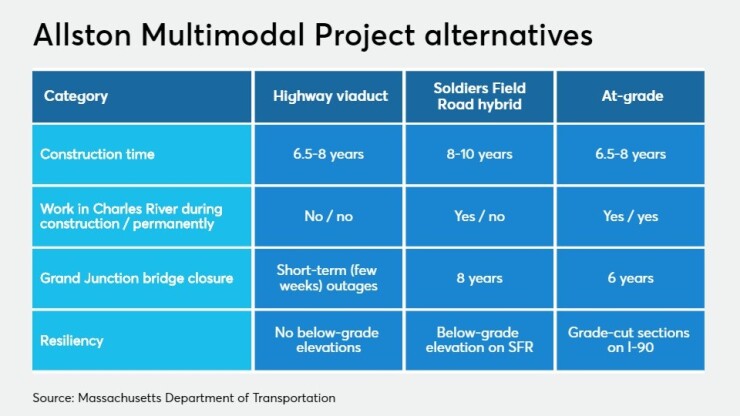

Pollack on June 22 proposed three

Without a preferred option, the commonwealth could simply rebuild the viaduct.

Business and community groups, according to Pollack, want quicker completion, less commuter rail disruption and no infrastructure construction, temporary or permanent, over the river.

“My [six] agencies would consider intrusion into the river excessive, especially if there are alternatives without any intrusion,” state Energy and Environmental Affairs Secretary Kathleen Theoharides wrote the MassDOT board.

Another report is due this month with the board to consider a preferred alternative in the fall, in time for the agency’s pending five-year capital program. Transportation officials have been meeting regularly with a task force.

“The fall is critical, not just because there have been six years and three attempts to reach a preferred alternative.” Pollack said.

While cost estimates were absent from the June 22 meeting, the effect of COVID-19 could weigh in the final decision. The pandemic has hurt state and local capital planning, according to municipal analyst Joseph Krist.

“There is a clear budgetary impact,” Krist said.

The Massachusetts Port Authority reduced its five-year, $3 billion capital plan, notably a Terminal E expansion at Boston’s Logan International Airport, by roughly one-third amid a worldwide slowdown in air travel. Logan passenger counts are 90% below year-ago levels.

Krist also cited declines in other Massport operated facilities. Two of Worcester Regional Airport’s three airlines ended service in June, while shipping volume has dropped at the Conley freight terminal in South Boston, New England's only full-service container terminal.

The memory of cost overruns to the Big Dig — formally the Central Artery-Tunnel Project — still hover in the Bay State, despite its improvements to the area’s transportation infrastructure. The final tab for that project soared to $24.3 billion from the original $2.6 billion estimate.

Mary Connaughton and James Stergios of Boston-based think tank Pioneer Institute urged the MassDOT board to revise its scoping report to minimize disruption for Metro-West commuters. Construction could require single-track Worcester commuter rail.

“Disruption is far too weak a word,” director of government transparency Connaughton and executive director Stergios said in a

They also urged MassDOT to fix Turnpike structures over state Route 128, about 10 miles west, before the start of the Allston project to avoid concurrent projects that compound traffic woes. “Those bridges are about eight years older than the BU viaduct, are also structurally deficient and in dire need of repair,” they said.

To build nothing and simply repair the viaduct is a non-starter for MassDOT board member and former Braintree member Joseph Sullivan.

“This is a forever decision, and I hope that we will be bold in that decision-making come the fall because it would be transformative,” Sullivan said. “It would in many ways create not only economic opportunities along that corridor, but also just a new vision.

“We need more time to make sure we have the underpinnings financially I order to carry out that ultimate preference."

“This whole project began because there is a serious maintenance problem,” Taylor said. “There is a safety problem that must be solved. The viaduct, it was carefully explained to me 10 years ago, needed attention. It needs more attention now.”