Moody’s Investors Service calls it “the great credit shift.” RBC Capital Markets calls it the new paradigm. Meredith Whitney calls it … well, let’s move on. The point is: the municipal bond market has transformed dramatically the last few years, opening doors for some and shutting doors for others.

Markit, a financial data provider best known for its valuation services in the credit default swap market, sees an open door as it launches a muni pricing service it says will be more timely, efficient and dynamic than the current competition.

Muni traders currently rely on the pricing services of Standard & Poor’s Securities Evaluation (often referred to as J.J. Kenny, its original branding), Interactive Data, and Bloomberg Asset Valuation, or BVAL. These services offer market makers the ability to discover and verify prices, plus manage risk.

Markit says its pricing technology on munis differs from these competitors because of technology it calls “parsing” — a rapid way to gather, organize and disseminate pricing data drawn from more than two million muni quotes per day.

It gathers data by looking at quotes contained in dealer-to-client messages and “axe runs” — dispatches sent through email or instant message services — that indicate what prices traders are willing to buy and sell at.

Markit sifts through the pricing information sent to money managers by market makers. It aggregates and makes them anonymous then dices them up into searchable bits before sending them off to other participants.

Through the service, the trader continues to receive proprietary emails from the banks it transacts with, but in a more organized way.

Markit made its name in 2003 when it launched a neutral service to provide similar information in the fast-growing but opaque credit-default swap market.

By collecting data from market makers, cleaning and aggregating it, and then sending it back to users, CDS traders could gain access to a market-wide perspective on particular credits, rather than the view of a single market maker. (The firm launched MCDX — now the benchmark index for muni CDS — in May 2008).

Along with its competitors, Markit also receives transaction data from the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board and new-issue pricing from its online EMMA system. The information is fed into a calibration engine which enables daily updates of nearly 3,000 prices.

The service went live with select participants in June and is available for others as of this week. At launch, it covers 900,000 individual muni securities, identified by CUSIP numbers. So far it includes investment-grade bonds including fixed- and floating-rate products backed by a general obligation pledge or one of 62 revenue types.

S&P’s muni pricing service covers around 1.4 million CUSIPs. Interactive Data evaluates more than 1.3 million. BVAL, the most recent entrant, covers more than 1.1 million, including 228,000 unrated munis and 39,000 in the high-yield space, according to a presentation 12 months ago.

Markit is still calibrating high-yield munis and putting together a model for nonrated bonds. The goal is to be fully immersed in the muni cipal market by the end of 2012.

The parsing methodology for munis is directed by Robert Vogel, who joined Markit in January 2008 to build its corporate-bond evaluated pricing service.

Before Markit, he spent six years as product manager of market data at Tradeweb; he also built an e-platform at BrokerTec, ran an in-house pricing system at Bloomberg, and was once a credit analyst at Fitch Ratings.

Vogel said the general methodology in the muni market has been to group bonds into generalized buckets and move prices in the entire bucket based on a few trades.

It worked great, until it didn’t.

With the downfall of the bond insurers in 2008, the muni market underwent a permanent shift as investors realized they could no longer ignore underlying credit fundamentals. Soft metrics like political will and hard metrics like debt-service coverage ratios or unfunded pension liabilities have become more important than they had been before.

This caused a dislocation between issuer ratings and credit spreads that Markit believes is significant and lasting, thus presenting opportunity.

“People started to look at the political environments of each state and the ability to deal, legislatively, with what are going to be enormously difficult financial situations,” Vogel said.

He describes the earlier period as a time when the market was on autopilot, whereas today’s muni market is “extremely name-specific, almost free-form.” One consequence is that long trading relationships between states with similar ratings, or between specific revenue types and GOs, have been divorced.

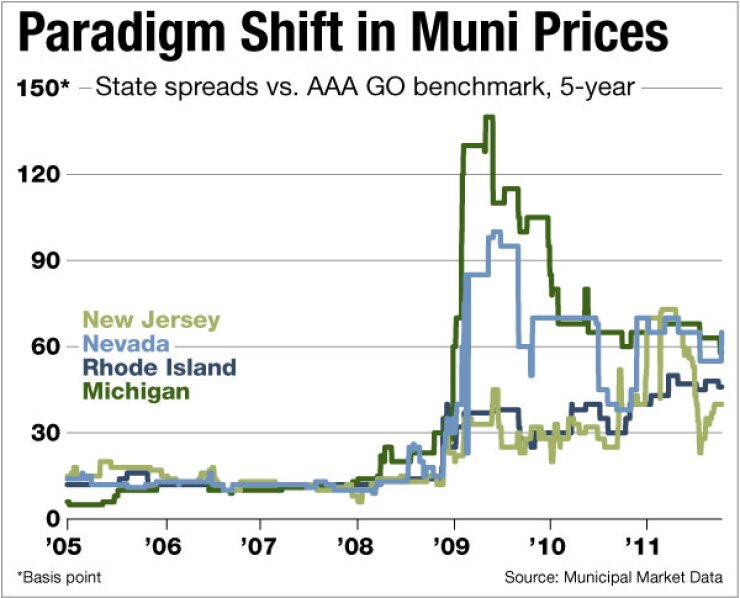

Municipal Market Data helps show the shift. In the years leading up to the credit crisis, names like Michigan, Nevada, Rhode Island and New Jersey traded in near-tandem. Since late 2007, each has courted its own path based on specific credit issues. Spreads between 10-year Illinois and California bonds are illustrative. In the three years leading up to the credit crisis, the spread between these two GOs fluctuated a mere 19 basis points, but since mid-2007 the spread has oscillated 214 basis points.

California spreads over MMD’s triple-A curve have averaged 103 basis points this year, while Illinois spreads have averaged 176 basis points. Both are multiples of anything seen before the credit crisis, and Illinois’ spreads are much wider even though it boasts a higher rating — Standard & Poor’s rates California A-minus and Illinois A-plus.

To Vogel, such dislocations indicate that investors are looking behind the ratings and basing their decisions on a range of metrics. In Moody’s words, a market that was “predominately driven by benchmark interest rates” is now governed by “underlying credit fundamentals.”

Markit senses opportunity because it sees the muni market going through the repricing dynamic experienced by the corporate market a decade ago, when bonds that once traded in a clearly defined box slipped into unchartered territory.

“All of a sudden that box exploded,” Vogel said. “All the fungibility in the corporate market went away, completely, unless you stayed within a name, within an asset class, within a seniority. It wasn’t apples to apples; it was granny-smiths to granny-smiths. From a risk perspective, it got that specific.”

The new market paradigm can be seen in the pricing of munis evidenced by transactions, but it’s less evident in the pricing models themselves, he said.

Markit’s competitors might disagree. Frank Ciccotto, senior vice president of securities pricing at S&P Securities Evaluations, said pricing services have undergone a major shift in recent years. The financial crisis made clients more insistent not only on accurate and consistent pricing, but on transparency, and servicers have responded.

“For most clients, the need to really understand how a price was arrived at wasn’t all that important,” Ciccotto said of the years before 2008. “Or if it was important, it wasn’t as critical as it is today.”

S&P Securities Evaluations is “very well-positioned to meet that growing demand,” Ciccotto said. He said S&P has spent the last year helping mutual funds and other clients to improve their ability to audit investments and “get under the covers” with vendors.

Still, Markit thinks there is room to bring a corporate credit mentality to munis and price specific bonds off specific events. Ideally, it would price bonds at something approaching “one issuer at a time.”

Vogel uses a lens analogy to explain how his staff will zoom in on a few quotes or trades on a local bond, and then zoom out to see how far they have to go to calibrate the model and capture all the price movements.

“Our methodology enables us to literally start at a single piece of evidence and then determine how far out we have to go to make a move,” Vogel said. “I don’t want somebody on my evaluation staff saying, 'I need to tighten the entire Georgia curve by 10 basis points’ — the market doesn’t work like that. Or, if it were to happen, he’ll have to prove it to me: that all GOs and all revenue bonds, at all rating levels and use of proceeds, are moving by 10 basis points.”

Markit has also developed a scale to measure liquidity — the ability to get in and out of a position at a reasonable transaction cost.

The scale tracks how often a bond is quoted or traded, what the bid-ask spreads are, and so on, and then quantifies the data onto a scale from 1 to 5. The lower the score, the more liquid the bond is.

The score is aimed at helping market participants manage risks and defend their valuations with quantifiable metrics.

Determining the liquidity of a bond can be particularly onerous: the 1.5 million of muni CUSIPs outstanding dwarf the 90,000 in the corporate market, and a huge portion of munis don’t trade daily.

BVAL recently developed a score to help clients assess the underlying data available to the valuation process. A BVAL score is an index number based on market data inputs including spreads, duration, and convexity, aimed at producing defensible valuations.

A New York-based muni trader who hasn’t used Markit’s service said a new competitor would be welcomed insofar as price discovery is often more art than science.

“It’s an art form to evaluate a bond based off other market data when you don’t have an arms-length transaction to base it on,” the trader said. “If Markit could bring more science than art, that could certainly be helpful.”