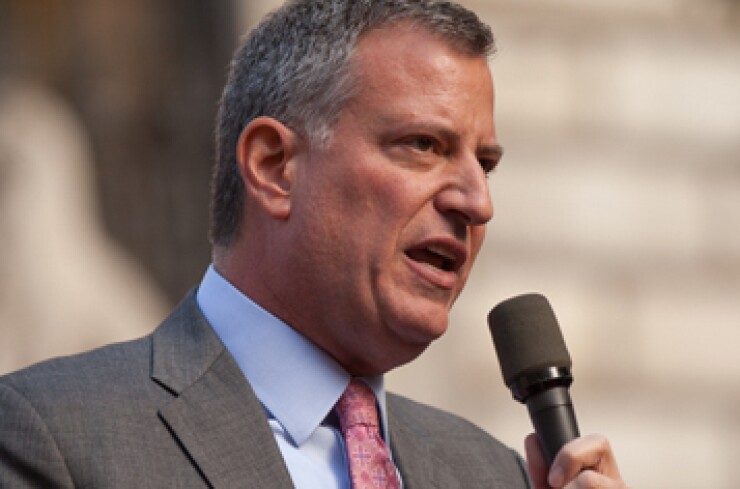

About a month into his first term, New York City investors some of them skeptical will get an initial glimpse of new Mayor Bill de Blasio’s approach to city finances.

De Blasio, who will succeed Michael Bloomberg on Jan. 1, must present his first budget to the City Council in late January or early February. Barring a stunning 11th-hour agreement between Bloomberg and the unions, settling expired contracts of roughly 300,000 municipal workers the contracts will be on the new administration’s front burner.

De Blasio, a Democrat who defeated Republican Joseph Lhota in a landslide on Nov. 5, campaigned on a left-leaning social agenda. Among other positions, de Blasio said he favors taxing wealthy individuals more to pay for pre-kindergarten and after-school programs.

“His first big test will be what to do with the expired contracts,” said Nicole Gelinas, a senior fellow at the free-market oriented think tank Manhattan Institute. “People have listened carefully and he hasn’t promised anything. He has essentially said to the unions that we’ll pay whatever we can afford.’ That means whatever you want it to mean.”

Unions backed de Blasio only after their first choice, former city comptroller Bill Thompson, plummeted in the polls right before the Democratic primary.

All city employee union contracts have expired.

Unions want retroactive pay, but de Blasio will inherit a deficit of as much as $2 billion in the coming fiscal year. And although estimates vary, 1% retroactive pay increases for 300,000 municipal workers could add $1 billion or $2 billion to a budget gap already at $2 billion.

The variables don’t end there. Pension and health-care costs are skyrocketing. With New York City fully covering the cost for nine of every 10 employees, health-care costs have doubled to $5.3 billion over 10 years.

“The scariest thing for the immediate moment is the expired contracts. Long-term, the scariest is health care,” Gelinas added.

Bond investors like New York City. Demand is high and interest rates remain low. But older analysts and investors worry that younger voters and bankers lack reference to the city’s infamous financial crisis of the 1970s or even the high-crime days of the early 1990s.

De Blasio’s critics also fear that his opposition to police stop-and-frisk policies could trigger a spike in crime rates and a resultant domino effect on other city dynamics, including investor confidence.

Other variables range from federal funding to Hurricane Sandy recovery to even the risk of further terrorism.

“The city must remain vigilant against growing budget gaps, the continuing cost impact of Sandy recovery and potential risks from the dysfunction in Washington as exemplified by the recent shutdown,” outgoing city comptroller John Liu said in his comprehensive annual financial report, issued three weeks ago.

But while investors don’t like uncertainty, analyst Richard Larkin doesn’t worry.

“The real professionals who follow this are not losing sleep because New York elected a fairly liberal mayor,” said Larkin, a senior vice president and director of credit analysis at HJ Sims & Co. “The city’s not going socialist.”

Larkin said many controls that began during the city’s stark financial crisis of the mid-1970s are still in place. “People are used to the mechanisms,” he said. “That’s not going to change under de Blasio.”

John Hallacy, managing director for public finance at Assured Guaranty Municipal Corp., said the city is in solid shape.

“We have the highest bond ratings we’ve ever had, at least since I’ve been working in 35-plus years, and there’s been a fair amount of stability and yes, there are many budget challenges, but the outyear gaps and such have been managed and the budgets [modified] quarter to quarter,” said Hallacy, speaking at the Nov. 6 Bloomberg state and municipal finance conference in New York.

“They’ve come up with the cuts they need to come up with. Overall the management of the process has been very good, and just speaking narrowly from an Assured perspective, we have billions of [dollars of] exposure to the city, so certainly we would like to them maintain the ratings.”

Howard Cure, speaking at the same conference, said New York City has amassed some goodwill over the past few decades. “You think about what New York has gone through — terrorist attacks; financial meltdowns, which would have a disproportionate impact on the city, hurricanes coming through; yet it’s still done very well,” said Cure, the director of municipal research at Evercore Wealth Management LLC.

Moody’s Investors Service rates the city’s GO bonds Aa2, while Fitch Ratings and Standard & Poor’s rate them AA. GO debt, however is only part of the story.

According to Liu’s report, GO debt rose to $41.6 billion in 2013 from $31.4 billion in 2004, up 32%, while Transitional Finance Authority debt more than doubled in that time, to $29.2 billion from $13.4 billion. The state legislature created the TFA in 1997 to enable the city to circumvent GO debt limits.

“Basically they have a fair amount of flexibility. You have to break it down to the different names, GO vs. TFA,” said Hallacy. “The city’s come to rely on TFA quite a bit more in the last several years. But that hasn’t been a problem because there’s a lot of growth in investment going right now on in the city. We see the office market coming back in a big way and the vacancy rates going down, and that ultimately translates to billable assessed value growth.”

Rachel Barkley, an analyst with Morningstar Inc., points out that debt levels will remain elevated, given projected capital needs and related debt financing. “The financial condition for the city remains strained despite its stringent financial management practices,” she said. “Strong institutionalized management systems and economic underpinnings should ensure the stability of dent service payments despite the likely continuation of fiscal pressure because of narrow operating margins.”

Barkley suggests that improved educational standards could pay financial dividends elsewhere within city operations. She cites the City University of New York system, which spends an estimated $38 million per year on remedial programs for students who come out of city schools unable to read at grade level.

“That’s money that obviously could be spent elsewhere within CUNY or even on overall city needs,” said Barkley.

Manhattan Institute’s Gelinas worries that variable debt amounts to 15% of the city’s debt load, leaving the city vulnerable to interest-rate hikes. “Interest rates won’t remain low,” she said.

But Gelinas doesn’t envision New York becoming another Detroit, at least for the short term. “It could be but not for a very long time,” she said. “That’s a 10-year to 20-year question.”