Illinois entered the new fiscal year with a budget in place, its unpaid bill backlog holding steady, and narrowing spreads in the secondary bond market.

Many potential pitfalls lay ahead as the state banks on help from the federal government and its voters to weather the COVID-19 pandemic’s fiscal wounds.

Revenues plummeted for the recently concluded fiscal 2020 after the economic shutdown ordered to slow the spread of COVID-19, but the numbers landed in line with revised estimates offered in the spring. The budget also fully funds statutory pension contributions.

Illinois entered fiscal 2021 July 1 in “brittle” condition, said Richard Ciccarone, president of Merritt Research Services.

The $42.9 billion budget is precariously cash-balanced, dependent on borrowing up to $5 billion through the Federal Reserve’s short-term Municipal Liquidity Facility borrowing program if new federal relief isn’t forthcoming and assuming voter approval in November to move to a graduated income tax structure from the current flat one to raise another $1.2 billion. If the graduated tax referendum fails, the budget relies on additional borrowing.

“If ever there was a time for the market to give Illinois some slack it’s now because we are in a national state of emergency," Ciccarone said. "This is a war against a pandemic but the budget is conditionally balanced” and can stay balanced if the referendum and federal aid come to fruition, “but there’s not a lot of room for things to go south.”

The timing of any borrowing plans remains in limbo.

“The MLF will only be tapped if needed. The FY21 budget authorizes it but doesn't require it. The state — all the states — are urging Congress to approve a federal aid package…to address revenue shortfalls created due to COVID-19,” said Carol Knowles, budget spokeswoman for Gov. J. B. Pritzker's administration.

The Fed's MLF program — established to help stabilize the municipal market — offers rates between 3.86% and 3.81% for eligible governments rated at the lowest investment grade level like Illinois. The debt can go out for up to three years. Illinois became the first to use the program last month with a $1.2 billion note issue to make up for delayed income tax revenue.

If aid doesn’t arrive soon, the state’s plan is to borrow but it’s also banking on eventually repaying it with federal aid down the line.

If Congress fails to provide state and local government funding in the near term and if voters do not approve additional revenue in November the governor will work with a special Legislative Budget Oversight Commission and lawmakers “to identify solutions for addressing any financial gaps,” the administration said.

After

Other states, like Illinois, are relying on some form of borrowing to weather the COVID-19 revenue losses but Illinois did not cut spending and it has no reserves. All but Illinois and three other states have cut some spending, Municipal Market Analytics said citing

Federal Aid

Pritzker is among local and state government sounding alarms in a push for new federal relief package to make up for lost tax revenues after the March CARES Act limited state and local government relief to coronavirus costs. Illinois cut its tax estimates for fiscal 2020 by about $2 billion and another $4 billion for fiscal 2021.

“Without that funding, imagine how difficult it will be to re-open schools and provide the resources we need for schools not to mention our public health infrastructure which is funded by state government,” Pritzker said during testimony last week before the U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security.

Pritzker supports the House Democrats’ HEROES Act to provide $1 trillion in aid to local and state governments. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has rejected the package that passed the House but said he expects additional relief will pass later this month but there’s been no commitment on the amount of local and state funds. A bipartisan proposal would direct $500 billion to local, county and state governments.

The fiscal uncertainty and risk of relying on federal aid is underscored in a mid-year state sector review S&P Global Ratings published Monday with the headline “States Will Continue To Be Tested In Unprecedented Ways.” S&P is maintaining a negative view of the sector for the second half.

“Additional federal aid is possible and would support credit stability, but the timing is uncertain and any lost-revenue replacement component will likely not cover all projected gaps,” S&P said.

Referendum

The fiscal year began as lobbying efforts over the progressive tax referendum heated up.

The constitutional amendment allowing a progressive income tax structure is the cornerstone of Pritzker's efforts to stabilize state finances by raising more than $3 billion in new annual revenue.

The wealthy governor contributed $51.5 million to the Vote Yes for Fairness Committee that is spearheading the effort, according to a July state election board filing. The committee is led by a former top Pritzker campaign aide. Pritzker previously directed $5 million to the group.

Business and farm groups earlier this month launched the Vote No on the Progressive Tax Coalition to fight the tax change.

“We stand united against the ballot question of doing away with the flat and fair income tax Illinois currently has and replace it with a punitive graduated tax that is going to punish all businesses and our family farmers,” said Illinois Chamber of Commerce president Todd Maisch.

At least 60% of voters casting a decision on the ballot question or a majority of voters casting a ballot are needed for the measure to prevail.

Spreads

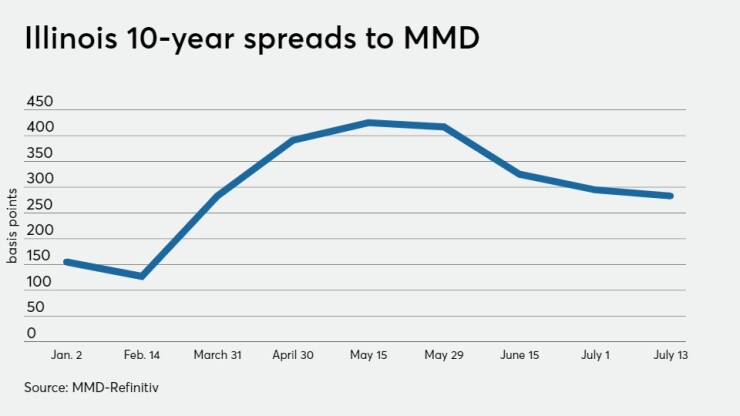

State spread penalties remain punishing but have eased in recent weeks after hitting peak levels stung by the market turmoil that hit troubled credits the hardest.

The state’s one-year was set Monday at a 253 basis point spread to the Municipal Market Data’s AAA benchmark, the 10-year was at a 283 spread and the state’s longest 25 year bond at a 269 bp spread.

On May 1, spreads were at 276/391/394 on the 1/10/25 bonds. On May 15 the spreads were at 400/425/425 and on May 29 the spreads were at 400/417/417.

On Jan. 2, Illinois spreads were 80/155/155 bp and showed some improvement as the year progressed landing at 80/127/132 on Feb. 14. After the pandemic shook the market the state’s March 31 spreads had widened to 175/283/286 and by April 30 were at 276/391/394.

Ciccarone said the spreads reflect a near-term horizon view. The state is being helped by its sovereign abilities to raise revenues and cut spending even though its credit quality is weakest among states.

“Investors are looking at the question of ‘will I get repaid’” at the same time they see the state offering an attractive yield, Ciccarone said. “There is some comfort in that it is a state general obligation.”

The unpaid state’s

It has ranged from $6 billion to $7 billion over the last two years having benefited from an infusion of $6 billion in borrowing in late 2017 and then steady tax revenue growth.

Federal funds to cover pandemic costs and $1.2 billion of short term borrowing through the MLF helped bring the backlog down. The borrowing also leveraged additional Medicaid dollars. The state closed on the deal June 5 at a rate of 3.82% for the one-year notes. The state received $2.5 billion on April 21 and $1.1 billion on April 27 from the CARES Act.

Comptroller Susana Mendoza sees trouble ahead.

“I took office in December of 2016 in the middle of what was then the worst fiscal crisis this state had ever seen — more than 2 years without a budget. This could turn out to be even worse than that,” Mendoza said, noting that debt service and pension contributions are a top priority.

Base fiscal 2020 general fund revenues fell $1.135 billion from the previous year after the COVID-19 shutdown hurt tax revenues and the state pushed off the income tax filing deadline to July 15, according to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability’s recently published

The state’s “Big Three” revenue sources felt the brunt of COVID-19, COGFA wrote. Personal income taxes fell $765 million, corporate income taxes dropped $308 million, and sales taxes declined $154 million net from last year’s levels.

The commission and Illinois Department of Revenue revised revenue estimates in the spring downward by $2.2 billion. The final numbers tracked closely with the commission and the Pritzker administration’s revised estimate.

Overall, the June revenue figure actually rose by $208 million but that was “mostly due to higher federal sources that reflected reimbursable spending made possible by nearly $1.2 billion of short-term borrowing proceeds,” said COGFA revenue manager Jim Muschinske.