CHICAGO – The political bickering that's driven the almost seven-month-old budget impasse in Illinois spilled into the public pension arena Thursday, leaving the state no closer to easing a fiscal burden that's saddled it with the lowest bond ratings of any state.

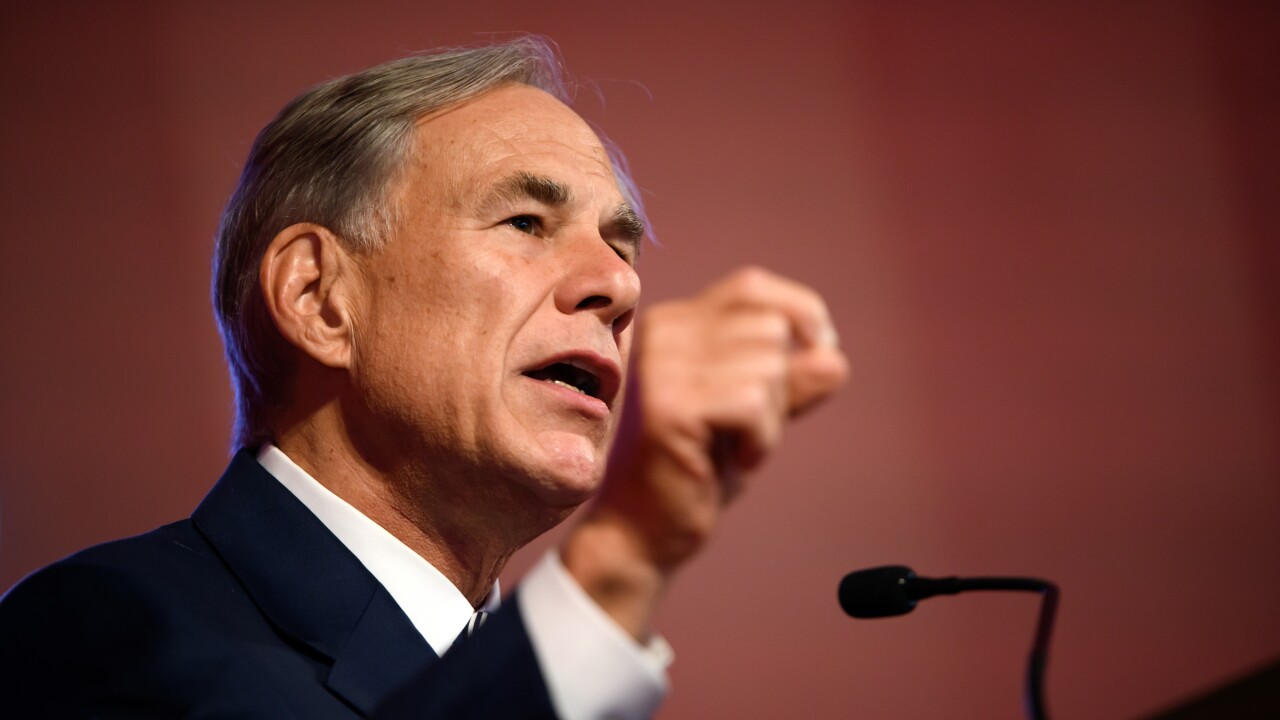

Gov. Bruce Rauner and his fellow Republican legislative minority leaders put their support behind a Senate Democratic pension reform plan that supporters believe won't run afoul of the state's stringent benefit protections.

Their support, however, was based on some revisions that the Democrats quickly rejected.

At a news conference with the House and Senate minority leaders, Rauner called the bill "a step in the right direction" and that he believes "with the wording picked properly, will be constitutional."

Rauner suggested that the plan's lead author, Democratic Senate President John Cullerton, was agreeable to changes.

But Cullerton quickly threw cold water on the Rauner endorsement.

"The plan he outlined at his news conference isn't what we talked about. It's not my plan," Cullerton said. "We apparently still have a fundamental disagreement over the role of collective bargaining in this process, in the sense that I think collective bargaining should continue to exist and the governor does not.

"This is not my plan, not the plan we discussed this morning, and it does not have my support," he added.

Rauner, who took office early last year, said he had resisted the plan previously because he did not believe it achieved sufficient savings, but said he had shifted his position "in the spirit of cooperation."

Rauner and the GOP leaders said the plan would trim about $1 billion off the state's pension contributions which are set to rise by $290 million in fiscal 2017 to $7.8 billion.

The plan would impact four of the state system's five pension funds, leaving the judges' fund out of it because the courts have been called upon to decide the legality of reforms.

The state Senate in 2013 passed Cullerton's original plan but it was rejected in the House and lawmakers eventually enacted House Speaker Michael Madigan's more expansive package that promised greater savings of about $140 billion in the coming decades, compared to Cullerton's $45 billion to $50 billion.

The Madigan plan cut benefits and raised employee contributions, but it was tossed aside in an Illinois Supreme Court ruling.

Cullerton had warning that his legal advisors believed the Madigan proposal would run afoul of the pension clause in the state constitution, and the state's high court justices agreed.

The court voided the reform package last May finding the benefit cuts violated the constitution's clause that gives contractual rights to membership in the funds and protects pension benefits form impairment or diminishment.

Supporters believe the legality of Cullerton's plan lies in contract law provisions that allow for "consideration" of changes to contract terms with employees if a cut is offset with a benefit.

Under Cullerton's original plan, employees would be asked to accept certain a cost of living cut in exchange for preserving their retiree healthcare subsidies. Employees could preserve both if they agreed to contribute more.

A wrench was later thrown in the healthcare choice by the high court's ruling in another case that applied the pension clause to retiree healthcare subsidies.

Cullerton revised his plan with a new choice proposed.

Current public employees would have the choice of keeping their current COLAs but future pay increases would not be counted toward retirement benefit calculations, or they could take a reduced COLA and continue to have pay raises counted.

Supporters of the Cullerton option believe it can hold up due to a footnote reference in the Illinois Supreme Court's May opinion that suggested the court might consider a plan that was negotiated with unions and offered some form of "consideration" for any changes.

Where Rauner and Cullerton now appear to be butting heads is on Rauner's insistence that the salary increase decision be removed from collective bargaining.

"In order for President Cullerton's bill to be constitutional, salary increases have to be taken out of collective bargaining," Rauner said.

Cullerton disagreed and Madigan accused Rauner of trying to divide Democrats.

"Despite the governor's desire to drive a wedge between Democrats in the House and Senate, neither President Cullerton nor I will agree to make changes proposed by the governor," Madigan said.

During the news conference, Rauner attacked Madigan saying he had "stonewalled and delayed" action on reforms.

Rauner later elaborated in a statement that followed the Democratic attack.

"Central to the Cullerton model is that future salary increases are part of the employee election, and that to ensure the proposal passes Constitutional muster current law must be changed to make the employee's election permanent. On that core principal, the governor's legal team and the President's legal team have agreed," a statement read. " If he no longer supports it, we urge him to immediately introduce new pension reform legislation that he thinks will be approved by the Supreme Court, and the governor will be open to considering it."

The GOP governor gives his second State of the State address next week amid a looming $5 billion deficit as the budget impasses continues.

Democrats want a tax hike to help close the gap and Rauner won't support one without Democratic support for his governance and policy proposals that include curbs on union powers over local government issues.

The state's unfunded pension tab continues to weigh on the state's balance sheet and credit profile although it's taken a backseat to the budget battle.

Illinois is the lowest rated state.

Fitch Ratings and Moody's Investors Service both place Illinois GOs at the BBB-plus level while Standard & Poor's assigns its A-minus rating.

Illinois' unfunded pension obligations worsened slightly in the last fiscal year while the funded ratio showed some modest improvement, according to data compiled and analyzed by the Civic Federation of Chicago.

The unfunded obligations grew to $112.9 billion for a funded ratio of 40.9% in fiscal 2015 from $111.2 billion and funded ratio of 39.3% a year earlier. The increase is more modest than the $11 billion added to the unfunded tab from fiscal 2013 to 2014.

The proposed fiscal 2017 contribution levels are up from previous projections due to weaker than expected investment returns and revised assumptions related to mortality rates and salary increases at several of the funds, the federation said.

"The state's funding plan and subsequently enacted changes defer a large portion of the required state contributions to later years and have been insufficient to prevent growth in the unfunded liability," the federation wrote.

The current funding plan took effect in 1996.