Arizona is earmarking $1 billion over three years to protect and expand its precious supply of water as persistent drought conditions shrink the output of the Colorado River, decreasing allocations for it and other parched states.

The money was included in a fiscal 2023 budget passed by the legislature, which also approved a bill that empowers a state agency to issue bonds for water supply development projects, including the importation of water.

“We are now in the second decade of the worst drought in recorded history, which, coupled with dramatic population growth in our state, makes the situation extremely serious,” Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke told a state House committee last week.

Arizona is one of seven states that depend on the Colorado River to provide water for 40 million people. That water supply is drying up and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

The ongoing drought led the bureau to declare its first-ever Colorado River

Water allotments to Arizona and Nevada were reduced, with the Central Arizona Project, which delivers Colorado River water to Maricopa, Pinal, and Pima counties — where more than 80% of the state’s population resides — seeing its normal supply cut by about 30%.

Buschatzke said he expects a tier 2 shortage to be declared later this summer for 2023, which will further reduce Arizona’s supply, making passage of the bill imperative.

“There are no other options,” he said.

The legislation, which passed with bipartisan votes in the House and Senate on Friday, makes Arizona’s Water Infrastructure Finance Authority — currently part of the Arizona Finance Authority — a standalone agency.

It would allow WIFA to sell long-term water augmentation bonds, enter into public-private partnerships for water-related facilities, and oversee water-related revolving fund programs. WIFA could also pursue bringing desalinated water to Arizona from Mexico, a plan Gov. Doug Ducey outlined in his January

In S&P Global Ratings’ ESG credit indicator report card, released in March, risks due to drought contributed to moderately negative environmental indicators assigned to Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah.

“This could necessitate long-term resource planning and require states to undertake more substantial capital investments that could affect its debt and liability profile to mitigate the effects of drought and other related natural resource pressures,” the rating agency said.

Utah’s score, which was largely based on long-term water supply challenges, drew

Ironically, Gov. Spencer Cox at the same time

And state lawmakers in the 2022 session

While Arizona looks for water from other sources, bond-financed projects elsewhere in the Southwest are targeting Colorado River water despite its shrinking volume.

“There is a scarcity challenge here and most of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked and there's a lot of ambiguity in terms of water rights and the allocation between the upper Colorado River states and the lower states,” said Chloe Weil, a S&P analyst.

The

Zach Renstrom, general manager of the Washington County Water Conservancy District, said drought, climate change, and rapid growth are spurring the project, which is projected to cost $1.3 billion to $2.2 billion.

“One thing the drought has really taught us is the importance of good water infrastructure and having more tools to utilize during a drought scenario to ensure people have safe drinking water,” he said. Utah’s 23% allocation of the upper river basin’s water shares will not be exceeded by the pipeline and “robust negotiations” are happening with the six other Colorado River states that had raised concerns about the pipeline, according to Renstrom.

“We’re not trying to steal anybody’s water,” he said.

But Oaks, the Utah state treasurer, said it is "highly unlikely” the project will move forward, citing the drought’s impact on water supplies, needed environmental approvals, and potential lawsuits from downstream states. If the project does proceed, it would likely be funded through a combination of state general obligation bonds, revenue bonds, and federal sources, with state lawmakers ultimately deciding how bonding would be used, Oaks added.

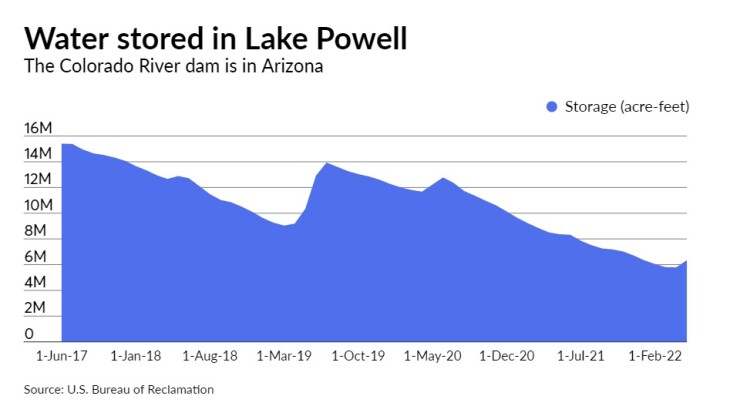

The optics of running a new pipeline to drain water from a Lake Powell reservoir that is

The financial risks of the pipeline are “quite high,” according to Zachary Frankel, executive director of the nonprofit Utah Rivers Council, noting the county would have to impose big water rate and property tax increases to pay back the state for the project, which would benefit a population with already high per capita water use.

In October, Fitch Ratings said the ultimate cost of the project, its final funding plan, and impact to the purchaser credit quality will be drivers of the district’s AA-plus rating for the near to intermediate term.

Triple-A-rated Denver Water is expanding the Gross Reservoir by raising the dam height by 131 feet to increase water capacity by 77,000 acre-feet. Construction began in April with completion expected in 2027. The reservoir, located in Boulder County, stores headwaters of the Colorado River that are sent through the Moffat Tunnel across the Continental Divide toward Denver.

The project, estimated to cost $464 million, is part of an approximately $1.5 billion, five-year capital plan that also includes the replacement of lead service lines and construction of a treatment plant. Denver Water sold its biggest water revenue bond issue last year, when interest rates were favorable, raising $350 million in a deal that attracted the lowest interest rates in the history of its bond program, according to Todd Hartman, a spokesman for the agency.

He added Denver Water will be issuing additional bonds in the coming months, although the approximate size and timing of the deal were not yet available.

Moody’s Investors Service said in a December report the utility anticipates financing 62% of the capital plan with bonds, with an estimated $550 million remaining to be issued.