Converting eligible state assets into a trust and using state lottery proceeds could benefit Connecticut’s public pension system, a state panel has recommended.

The 13-member Connecticut Pension Sustainability Commission, whose work since October 2017 included six months of hearings, issued its

“Connecticut continues to face the consequences of decades of failure by prior administrations to adequately and responsibly fund the state’s pension obligations,” said the report.

Project managers, actuaries, academics and other experts from across the country provided verbal and written testimony.

The legacy obligation trust concept involves a government unit making an in-kind contribution of real assets — such as land, buildings, infrastructure or enterprises — to a professionally and independently managed trust.

While the LOT would be the first in the U.S., precedent exists for the use of in-kind contributions to satisfy legacy obligations such as bond debt.

Examples include the Detroit bankruptcy settlement, the state-owned Queensland Motorways in Australia, the New Jersey lottery and Connecticut capital Hartford’s transfer of the title to the city's Batterson Park to the local pension fund.

"The big conclusion is that the trust vehicle concept can work. It can be used as a viable vehicle for unlocking equity value,” said committee member

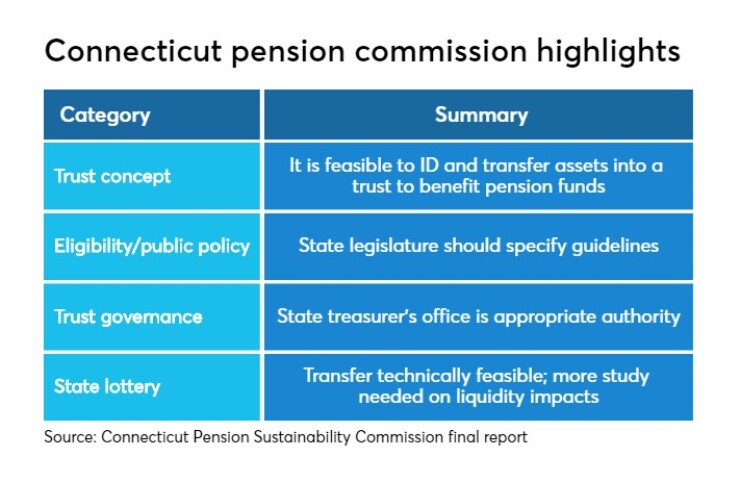

The commission recommended the legislature issue policy guidelines in advance. The state treasurer’s office, the report said, is appropriately suited to coordinate the effort.

"While we were able to identify assets held by the state, we couldn’t conclude on which assets to recommend as it might conflict with public policy,” Imber said. “We need more guidance from the legislature as every asset has a constituency or stakeholder."

The report also suggested continuing the commission to avoid having another state entity duplicate its work. State Rep. Jonathan Steinberg, D-Westport, chaired the panel.

Connecticut’s fiscal picture provides a backdrop.

While the state, a frequent municipal issuer, received across-the-board rating downgrades in 2017, it received two upward outlook revisions of late.

Kroll Bond Rating Agency last week revised its outlook on Connecticut general obligation bonds to stable from negative while affirming its AA-minus rating. S&P Global Ratings in March bumped its outlook to positive from stable on its A rating. These mark the first two upward rating agency swings for Connecticut GOs in 18 years.

"The financial sector is paying attention to the positive changes happening in Connecticut," said state Treasurer Shawn Wooden, who ran point on a restructuring of the teacher pension plan, which the legislature approved this year.

Moody’s Investors Service rates Connecticut GOs A1, while Fitch Ratings rates them A-plus. Outlooks from Moody's and Fitch are stable.

The state plans a $244 million refunding for July 25.

“Spending growth is driven by rising costs for pension and retiree health expenses, as well as Medicaid, crowding out other more discretionary state spending,” Moody’s said last week. “Pension contributions remain a very significant and growing part of the state's budget.”

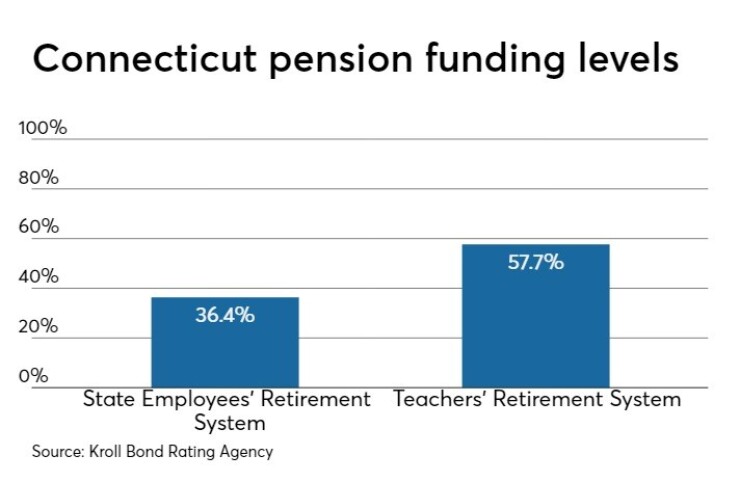

Connecticut administers two major pension plans, the State Employees’ Retirement System and the State Teachers’ Retirement System. It also administers the much-smaller Judicial Retirement System. The state’s funding levels for SERS, according to a Kroll report released Thursday, is 36.4% and 57.7% for TRS.

Pew Charitable Trusts considers an 80% level acceptable.

The state has contributed to these funds at the full actuarially determined employer contribution in recent years, “but funding progress has lagged as realized investment returns have not reached actuarial assumptions,” Kroll said.

Pension overhaul is but one item on a crowded plate for Connecticut lawmakers. Other challenges include

The legacy obligation trust alone is no silver bullet, according to Imber.

“It can move the needle if sufficient assets are contributed but maximizing value must be in the context of pension and budgetary reform, he said. “In other words, run a smooth budget process, eliminate structural deficits, eliminate gimmick ‘one-shots’ to balance budgets, and minimize borrowing.”

Connecticut’s proposal needs an accounting perspective, said

“As an example it is talked about ‘making an inventory’ when it should be talking about making a proper market valuation,” Detter said, citing research by Ian Ball, a public finance professor at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Commercial assets owned by the public sector urgently need professional management, Detter added. “There can be no professional management without such a vehicle — and the best place to start is most likely at the local level.”

The concept is open to public-private partnerships, according to Detter.

“Properly designed and implemented they can benefit both the public and the private partners,” he said. “Too often they have been no more than vehicles to avoid public sector budgetary and balance-sheet constraint, in the process transferring most of the gains to the private partners.”

While using Connecticut Lottery proceeds to benefit the pension funds or the wholesale transfer of the lottery is “technically feasible,” the commission urged further study on how either action would affect the pension funds’ liquidity.

Some committee presentations focused on New Jersey’s experience. That state’s

New Jersey’s transfer, though, took that revenue stream away from a general fund budget, where it had backstopped education and senior-citizen oriented programs. Bond rating agencies generally regarded the move as credit neutral or slightly credit positive.

“I would not be surprised if the [Connecticut] legislature signed onto the lottery,” said Alan Schankel, a managing director at Janney Capital Markets in Philadelphia. “I’m not sure that they’d be supportive of putting real estate in there.”

Schankel is skeptical about the LOT concept.

“It might help the funding on the surface, but it wouldn’t add to the cash flow and at the end of the day, that’s what you need,” he said.

Employers and employees alike should share investment losses, said James Spiotto, a managing director at Chapman Strategic Advisors LLC in Chicago. Unaffordable pension benefits, he said, partially stem from the additional payments needed to compensate for investment losses or failure to achieve investment goals.

Spiotto cited loss-risk sharing approaches on invested funds and rates of return in the state of Wisconsin — whose employment pension plan is virtually 100% funded — the New Brunswick Public Service Pension Plan in Canada and some European plans.

Balanced budgets that fully fund essential services, necessary infrastructure improvements and economic stimulus are also necessary, Spiotto said.

“Economic development accompanied by increased revenue is the high tide that raises all boats.”