Undaunted by municipal broadband failures elsewhere in the nation, Colorado cities are aggressively pursuing fiber-optic bond projects in the face of corporate competition.

Foremost among the success stories is the northern Colorado city of Longmont, whose NextLight fiber optic network was rated by PC Magazine

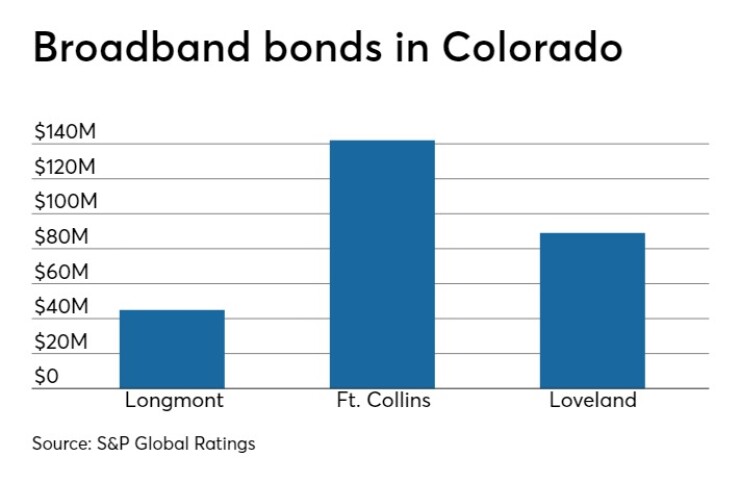

Four years after issuing $45.3 million of bonds to finance the network, Longmont, population about 90,000, expects to pay off the debt by 2029, if not sooner. NextLight serves 18,300 internet customers in a city of 34,538 households.

“Original projections indicated a maximum market penetration rate of 36% by 2018. As of May 15, 2017, however, the system has achieved a 51% take-rate,” S&P Global Ratings analyst Doug Snider wrote two years ago about the combined utility, rated “A” with a stable outlook. “This unexpected growth has contributed to Longmont Power and Communication's higher-than-anticipated revenues as well as a need to expand the utility's fiber-optic infrastructure.”

Almost a year ago, nearby Fort Collins, Colorado's fourth-most-populous city with more than 156,000 residents, issued $130 million of revenue bonds for the city utility’s Connexion broadband network that is expected to sign up its first customers this year. The serial bonds reaching final maturity in 2042 received ratings of AA-minus from S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings.

The bonds, and their ratings, are supported by the city's established monopoly public electric utility. Fitch, in its rating analysis, cited strong public and political support for the project, evidenced by voter approval of two ballot measures.

S&P cited the performance of the electric utility as supporting the AA-minus rating, while noting that the broadband initiative creates some unknowns.

"While we view management as a capable steward of the electric utility, it has little experience in running a broadband system," its analysts wrote. "Fort Collins and its advisors have done significant due diligence in researching and planning the broadband project, but the utility has yet to staff key operational and oversight functions, so this remains a credit risk."

The city, which received internet service almost entirely from Comcast and CenturyLink, is aiming for a residential price of $70 per month for 1GB per second speed, with offers of phone, video and internet.

Now Loveland, between Fort Collins and Longmont, is joining the parade with an $89 million bond sale planned for later this month. The bonds could allow the city-owned Loveland Power and Water Utility to offer broadband service as early as next year.

Alan Krcmarik, acting finance director for the city of 76,000, said the success of Longmont’s network was a key factor in proceeding.

“We understand that this is a huge project,” Krcmarik told The Bond Buyer. “The council and city staff have exercised due diligence and caution. Based on Longmont’s success, we believe the Loveland market will likely respond in a similar way.”

Officials in Loveland, who consulted with Chattanooga, Tennessee, before launching their fiber system, said the Tennessee city's venture is considered very successful. With 100,000 phone, internet and video customers, Chattanooga signed up three times more customers in 18 months than originally anticipated; in a Jan. 29 report, S&P viewed Chattanooga’s debt-free fiber-optic system as a positive credit factor in the public EPB utility’s “AA” rating and stable outlook.

Krcmarik said the bonds will price through a syndicate led by JPMorgan, with executive directors Antti Suhonen and Pedro Ramos as lead bankers. Hilltop Securities director James Manire is municipal advisor. The Loveland deal will include $60.9 million in 30-year tax-exempt bonds and another taxable series of $28.79 million.

S&P rated the bonds A-plus with a stable outlook. The rating is largely supported by the established water and power utility.

“A number of uncertainties exist, including construction of the system itself, take rates, and competitive responses by commercial entities that offer internet, phone, and video services,” S&P wrote. “In comparison with the general stability of public power electric utilities, the operating environment for telecommunications services is much more dynamic.”

Like the neighboring municipal broadband networks, Loveland’s will face competition from Comcast and CenturyLink when it begins offering service next year.

“Given the take rate of 42% for residential customers and 27% for businesses, the broadband enterprise is projected to have positive net operating income in year five and net cash exceeding liabilities in year 21,” S&P said. “However, the competitive decisions of Loveland Water & Power, Comcast, CenturyLink, and possibly other companies offering substitutes will shape the marketplace.”

Longmont, Fort Collins, Loveland and nearby Estes Park, another city moving into broadband, share ownership of the Platte River Power Authority, which already has a fiber optic loop in the region. Longmont tried to partner with a private-sector internet service provider in the 1990s, but the effort fell through in 2000.

More than 100 municipalities have opted out of a 2005 Colorado law that forbids local governments from controlling broadband services unless their voters approve. While some of those cities have since developed their own broadband utilities, others are leaving their options open.

In 2011, voters backed Longmont’s proposed exemption from Colorado Senate Bill 152, though Comcast and other corporate providers spent $419,000 to defeat it.

Twenty states had outright bans or legal barriers to municipal broadband as of 2018,

“In spite of these corporate efforts, 108 communities throughout the USA currently offer citywide access to publicly-owned fiber Internet, and 24 states feature at least one citywide FTTH [fiber to the home] municipal broadband networks,” the site says. “Those numbers have only grown in the wake of the FCC’s removal of Net Neutrality.”

Opponents of municipal broadband point to failed efforts like those in Burlington, Vermont and Memphis, Tennessee, as cautionary tales.

“More than 450 communities are estimated to have some form of taxpayer-funded, government-owned internet service, including more than 80 cities with large-scale public fiber-to-the-home broadband networks,” the Taxpayers Protection Alliance says in a 2016

In 2004, Provo, Utah, issued $39 million of bonds for its iProvo broadband network that by 2011 required a $5.35 surcharge on electric bills to make bond payments. Two years later, the city sold the $39 million network to Google for $1. Google agreed to provide free 5 megabyte per second internet to residents for seven years, along with free internet services to public institutions and schools. Ratepayers were left with $3.2 million in bond payments for 20 years.

Supporters of municipal broadband note that iProvo was handicapped by state legislation backed by private cable and fiber networks that required municipal broadband to offer wholesale service rather than retail. The network was also developing as the nation was headed into recession.

Another Utah municipal broadband network, the Utah Telecommunications Open Infrastructure Agency, known as Utopia, has been cited by critics as a boondoggle, but the network, founded in 2008, earned sufficient revenue in 2018 to cover bond payments and a 2% dividend to member communities.

Eight of the member communities in Utopia in 2011 created the Utopia Infrastructure Agency to accelerate network expansion. UIA provides a way to finance payments using bonds backed by subscribers and issued by the participating cities. In 2018 Woodland Hills, Utah, joined the 16 cities that have added Utopia fiber built since the original 11 member cities formed the agency in 2004.

“The existing private provider’s services weren’t cutting it,” said Utopia executive director Roger Timmerman. “This shows that the Utopia Fiber system is working and we anticipate more cities partnering with us in the near future.”

The original Utopia “pledging” cities issued $185 million for construction costs using sales tax pledges as collateral. After its formation, UIA issued an additional $77 million of bonds.

Last month, S&P conferred its A-minus long-term rating to $2.73 million series 2019 UIA bonds for Utopia’s Morgan City project. Morgan City has also pledged an annual maximum of $90,360 each from both sales tax revenues and electric fees in the event of a shortfall of UIA revenues.

“The stable outlook reflects our expectation that the utility will make the necessary rate adjustments to pass through increasing power costs and debt service in an amount that will produce commensurate with the rating,” analyst Doug Snider said.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit that supports local initiatives in areas like energy, communications, banking and retail as an alternative to national corporations, says cities need to act proactively to obtain municipal broadband is available to residents and businesses,

“In the case of muni systems, which are not-for-profit enterprises, one measure of ‘success’ is defined as the level of their ‘take rate,’ that is, the percentage of potential subscribers who are offered the service that actually do subscribe,” the Fiber-to-the-Home Council North America wrote

“Nationwide, the take rates for retail municipal systems after one to four years of operation averages 54%. This is much higher than larger incumbent service provider take rates, and is also well above the typical FTTH business plan usually requiring a 30-40% take rate to break even with payback periods,” the report said.

“I think that there are far more success stories than failures, but you wouldn’t know that from reading a lot of press accounts,” Loveland spokesman Tom Hacker said of the municipal broadband sector. “We looked at notorious failures and spectacular success and everything in between. It took a lot of work to put together a plan that would be politically palatable and financially successful.”