BRADENTON, Fla. — As Jefferson County, Ala., slogs through the nation’s largest municipal bankruptcy, at least 10 bills that provide various forms of fiscal relief for the county are being advertised in advance of this year’s regular legislative session, which begins Feb. 7.

Most of those bills have been proposed by Jefferson County, which faces a general fund deficit of as much as $40 million this year due to the loss of an occupational tax that was struck down by Alabama courts.

At the same time, county officials are making plans to cancel several economic development contracts, and to lay off hundreds of workers in addition to the more than 500 employees who were laid off last year because the occupational tax revenue was lost.

Many of the county’s bills — which have yet to find sponsors — propose various taxes and fees on items such as vehicle tags, the storage of personal property, and an unspecified amount of occupational tax, with proceeds going to the county’s general fund for use as the County Commission sees fit.

One bill would provide replacement revenue for the general fund from an unspecified amount of sales and privilege taxes and, in certain cases, to provide “for payment of principal and interest coming due on the general obligation indebtedness of the county.”

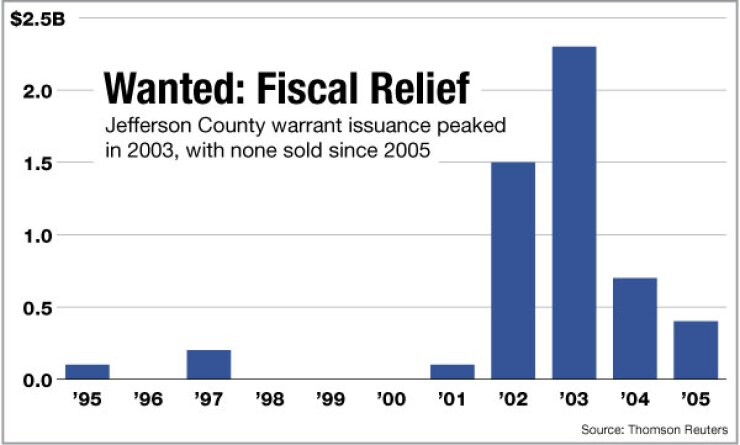

Jefferson County, the home of Birmingham, filed for bankruptcy on Nov. 9 after failing to reach a restructuring agreement on $3.14 billion of sewer warrants, which are in default.

Most of the sewer debt is in variable- and auction-rate mode.

In addition, the county’s debt includes $814.7 million of school warrants secured by a one-cent sales tax, $200.52 million of GO warrants, and $82.5 million of limited-obligation lease warrants.

The county has defaulted on $105 million of the GO warrants, which are in variable-rate mode with accelerated payments.

Before filing for Chapter 9, state lawmakers representing Jefferson County refused to provide fiscal relief through replacement revenue for the occupational tax that was struck down.

In Alabama, counties do not have home rule and rely on the Legislature for authorization to raise revenues, including all kinds of taxes.

State courts ruled that the occupational tax authorized by the Legislature was implemented improperly.

Some local legislators refused to grant fiscal relief as the county negotiated with creditors holding the sewer warrants because settlement talks included an increase in sewer rates to support restructuring the debt, while other lawmakers refused to authorize new revenues unless Jefferson County filed for bankruptcy, according to testimony in December bankruptcy hearings.

“I think bankruptcy is the wrong decision for the county,” said Sen. Slade Blackwell, a Republican who represents a portion of Jefferson County.

Blackwell said the county could withdraw its Chapter 9 petition, but at this point the bankruptcy judge has several rulings pending that will determine the next course in the case, including a determination about whether the county is eligible to file for bankruptcy.

“Some unintended consequences will fall out of this,” he predicted. “We’re already seeing that in some [economic development] contracts that the county is canceling. If you look at the big picture, I think it will also hurt economic development and future growth in the county and in [Birmingham].”

“One of the things I hate is that some of those who will be hurt most will be small businesses that work with the county and the city,” Blackwell said. “They don’t have anything to do with the sewers.”

Blackwell said that some lawmakers did object to the county’s restructuring negotiations with creditors because the resolution would require raising sewer rates, but that if the bankruptcy case goes forward, a plan of reorganization still could include an increase in rates.

“We don’t know what it will look like,” he added, referring to what the final reorganization plan will require.

Blackwell said he has not yet proposed any bills for Jefferson County for the upcoming session, but he would support a solution to the sewer debt problem and the general fund shortage.

“I would like a solution that helps over the long term,” he said. “The big problem is that everybody doesn’t understand there’s still a $40 million hole in the general fund that you have to plug.”

Regardless of the bankruptcy case, Jefferson County will need a new source of income to support the general fund, or commissioners will be required to reduce services, Blackwell said.

Meanwhile, several major decisions are pending before federal bankruptcy Judge Thomas Bennett.

The automatic stay that comes with a bankruptcy filing remains in place through Friday.

The stay freezes lawsuits and actions by creditors, or anyone acting on the county’s behalf.

At issue with regard to the stay is whether the state court-appointed receiver who currently is in charge of the county’s sewer system, John Young, remains in place to operate the system and pay its bills, including debt service.

A state judge appointed Young receiver in September 2010 at the request of the trustee, Bank of New York Mellon, after the county defaulted on the sewer debt.

Attorneys for Jefferson County said in court documents that the bankruptcy filing, and automatic stay, requires Young to return the sewer system and its revenues back to the county’s control.

Young has asked Bennett for permission to remain in charge of the sewer system and its finances while the bankruptcy case proceeds.

Though Bennett has not made a final determination about the receiver’s authority, he has ruled that he will not consider arguments based on the Rooker-Feldman Doctrine and the Johnson Act.

Rooker-Feldman prevents a federal court from undoing the judgments of a state court, while Johnson prevents a federal court from issuing a ruling that affects rates charged by a state-chartered utility.

Young has indicated in court documents that he may appeal Bennett’s ruling on Rooker-Feldman and Johnson.

Another major decision pending before the court concerns the county’s eligibility to file for Chapter 9, a decision that some experts say has the potential to delay Jefferson County’s case for as long as six months.

Last month, Bennett heard arguments that the county may not be qualified under Alabama law, which requires local governments to have bonds or refunding bonds outstanding to be eligible to adjust debts using Chapter 9 bankruptcy.

In Alabama, bonds require approval from voters in a referendum, but not warrants. The county only has outstanding warrants.

Bennett ordered participants in the case to file additional briefs by Dec. 28 with suggested wording that he may, or may not, submit to the state Supreme Court to determine if Alabama law authorizes warrants as a form of debt that qualifies for bankruptcy.

Jefferson County has filed with the court 155 pages listing more than 1,000 creditors and $4.61 billion that they are owed.

The county has also filed a notice saying that it “disclaims and disputes any recourse liability” to all limited obligation, non-recourse claims, which includes the outstanding sewer and school warrants.