At a time when government is shrinking, the new office overseeing New York’s public authorities is looking to expand. The Authorities Budget Office, created under reform legislation last year, wants to add four new staff members in the near term as the agency writes regulations over the next six to eight months.

“It’s going to take some bit of time to initiate all the responsibilities we have under the new act,” said acting director David Kidera. “We’d like to go faster but given it’s only been six months and we only have six people, I think we’re doing remarkably well.”

The Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009 created the new ABO, which is part of the Department of State and oversees most public authorities in the state. The original ABO, created in 2006, had a more modest oversight role, collecting financial information from public authorities.

Critics of public authorities have often refered to them as a “shadow government” and called for a beefed-up office to increase transparency. The new office has subpoena power, collects financial information from authorities, and considers potential consolidations or eliminations of authorities.

The ABO covers 472 active authorities, including 47 state authorities, 114 industrial development agencies, 123 other local authorities and 188 local development corporations. There are also about 190 local public housing authorities and three bi-state or international authorities that are not subject to the office’s jurisdiction.

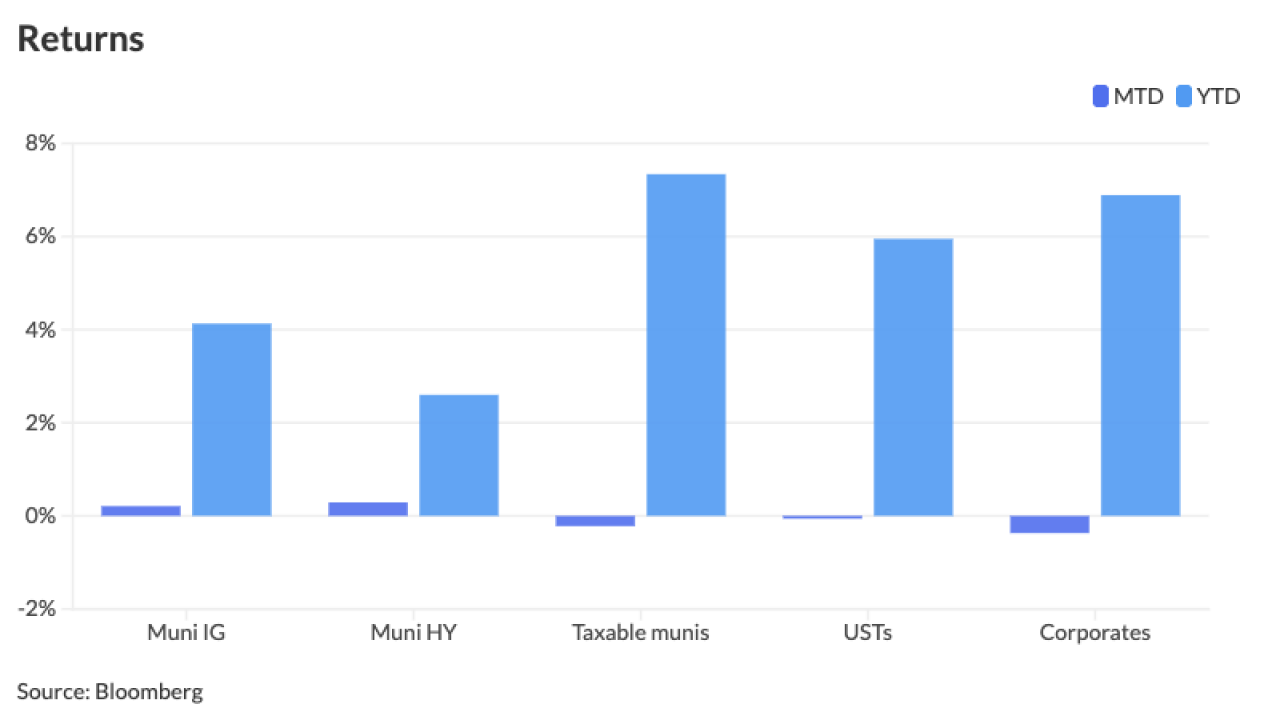

As of 2009, outstanding public authority issued debt in New York totaled $126.91 billion, according to an ABO report. That included $46.88 billion of state-backed debt, $50.14 billion of authority obligated debt, and $29.89 billion of conduit debt.

Though Kidera was director of the previous oversight agency — the similarly named Authority Budget Office that was created in 2006 under a previous reform effort — he has had to create the new office from scratch. The ABO is nearing the end of a bureaucratic process to establish its organizational structure and create permanent positions.

At a time when the state has a hiring freeze due to the weak economy, the ABO has had to get waivers to hire people. Kidera said the office plans to hire one or two attorneys and probably two policy analysts to supplement its current compliance team over the next four to six weeks. Four new hires would bring the staff, including Kidera, up to 11, which is what its $1.8 million budget covers.

Earlier this month, a task force headed by Ira Millstein, a senior partner at Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP, said the ABO needed a staff of 30 in order to carry out its duties.

The task force supported the agency’s internal analysis that said it needed 24 to 40 people and a $4 million budget, according to Kidera.

He said the office’s organizational structure will likely evolve into three divisions. One would be a small legal team.

Another would carry out compliance and enforcement actions, including audits and looking at complaints or concerns raised by the Legislature or whistleblowers. A third would deal with analysis and policy issues such as debt practices and consolidation or elimination of existing authorities.

Under the new law, which took effect on March 1, ABO board members now have an explicit fiduciary duty to the authorities on which they serve rather than to the official who appointed them.

Board members have to sign a statement that says they understand their duty. The ABO provides the form board members must sign.

“They all want to tweak it a little bit,” Kidera said. “We did not allow that.”

Authorities don’t need to return the forms but Kidera said they have had an excellent response.

If the ABO determines that a board member has violated his or her fiduciary duty, the office has no power to fine them or remove them. The first step would be to contact the board member directly to let them know there is a compliance issue.

“Through the regulatory process, we will more clearly define what is means to be censured, how we would go about censuring, what a board would have to do to warrant censure,” Kidera said. “So that will all be spelled out through regulations.”

The ABO would need to take care in how it handles such actions, but it is “a serious stick that we hope would enforce compliance,” he said.

“All we really can do is sort of admonish them publicly,” Kidera said. “These are private individuals who have businesses and careers and all the rest, so I think any formal reprimand or admonishment that we would make could have an effect on these individuals in their private lives.”

If the ABO felt there was a serious violation of fiduciary duties, it would go to the official who appointed the board member and ask that they be removed.

The office has already done this. The state inspector general released a report this year critical of the New York State Theatre Institute in Troy, which was created by the Legislature.

The ABO consulted with the inspector general’s office, reviewed documentation from the institute, and recommended that Gov. David Paterson remove the entire board because it “demonstrated a persistent pattern of neglect in the performance of its duties and fiduciary obligations.” The governor agreed with the recommendations and began the process to do that.

State authorities are required under the act to submit mission statements to the ABO. All but two have complied: The Erie County Medical Center and the Jobs Development Authority. The JDA, which operates in conjunction with the Empire State Development Corp., is in the process of complying, Kidera said. Some hospitals have “a hard time defining themselves as an authority,” he said.

Assemblyman Richard Brodsky, D-Westchester, who chairs the Committee on Corporations, Authorities, and Commissions and was the main push behind the reform act, said the law is “off to a good start.”

“It’s major, major reform and it’s going to take some time to break in,” he said. “The transparency pieces are working quite well [but] I don’t think the Authorities Budget Office has quite figured out how to enforce violations.”

One area that the reform did little to address was the role of authorities as vehicles for issuing state-backed debt.

Charles Brecher, director of research at the Citizens Budget Commission, a fiscal watchdog organization, said the law requires better reporting on authority debt but does not limit it.

“What’s needed is a revision to the constitutional debt limit and nobody wants to take that on,” he said. “The notion that we ought to close this back-door mechanism to put some limit on it is a concern of people who would like to reform the state’s fiscal practices.”

Brecher said that despite statutory debt limits, the Legislature just raises that ceiling when it wants to.