What do you get when you mix a protracted recession with a series of overly optimistic projections and a credit guarantee from a borderline insolvent bond insurer?

Answer: the Las Vegas Monorail.

The ambitious monorail project is in default on its debt and is likely to remain in default, according to the project’s trustee, Wells Fargo Corporate Trust Services. The math is not complicated: the system generates far less money than it owes on its debt.

In headier times, Sin City figured it was time to build a rail system ferrying riders in an air-conditioned monorail through the desert heat to the hotels, casinos, and convention center along the Las Vegas Strip.

The Nevada Department of Business and Industry had a plan.

The DBI in 2000 sold nearly $650 million in bonds in a deal underwritten by Salomon Smith Barney and Banc of America Securities.

The department lent the proceeds to the newly created entity called the Las Vegas Monorail Co. The company used the money to build a nearly four-mile monorail stretching from the MGM Grand to the Sahara Hotel & Casino.

The monorail was to charge passengers a fare, and the fares plus some advertising revenue would be used to repay the loan.

The bonds were broken into three pieces — a senior piece, a second-tier portion, and a subordinate portion.

The senior tier was insured by Ambac Assurance Corp.

The 30-year piece of the senior deal in 2000 priced at a yield of about 6% — at the time just 50 basis points above the triple-A Municipal Market Data scale.

The bonds were secured only by the revenue created from the monorail, so key to the creditworthiness of the debt was how many people would ride and how much they would pay.

The DBI hired a consultant, URS Greiner, to estimate how many people would ride the system and consequently how much revenue the system would generate to repay lenders.

URS Greiner employed a regional transportation model called the Modified RTC Model, which forecast ridership based on such factors as hotel stays, socioeconomics, and traffic congestion.

According to the bonds’ 2000 offering statement, the consulting firm concluded roughly 19.5 million people would ride the system in its opening year in 2004, and then ridership would grow about 1.7% a year for the next five years.

That meant that by 2009, the system would be shuttling 21.2 million people a year.

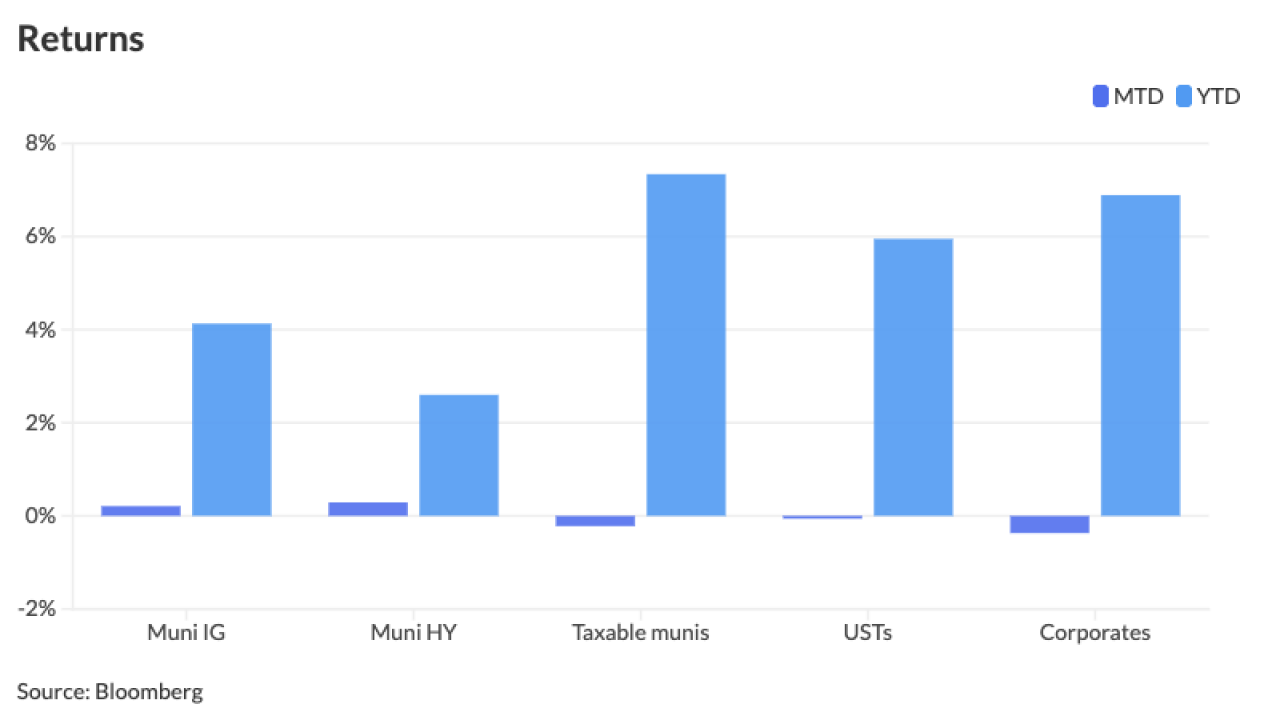

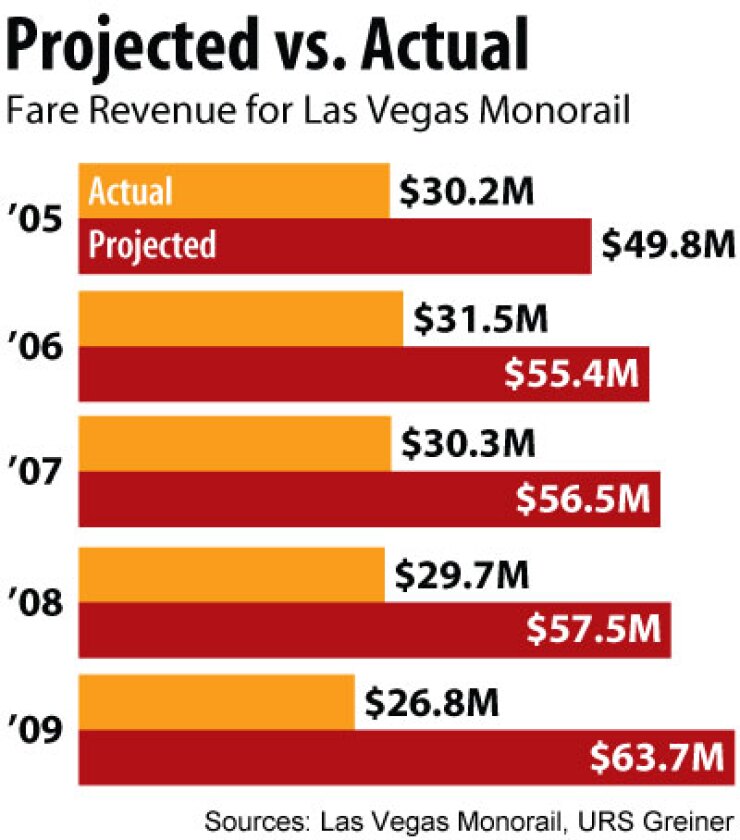

Based on that forecast, and an assumed fare of less than $3, URS Greiner projected fare revenue of $48.8 million in the system’s first year. By 2009, the system would generate $63.7 million in annual fare revenue, URS Greiner concluded.

The forecasts were way off.

In its 2010 budget, the monorail anticipates 6.2 million people will ride the system this year. Ten years ago, URS Greiner’s projection for 2010 ridership was 21.6 million.

The Las Vegas Monorail estimates it generated $26.8 million in fare revenue last year — shy of the forecast by almost $37 million. And that is even with the monorail charging $2 more per ride than initial projections anticipated it would charge at this time.

Considering the loan was to be repaid with revenue left over after paying operating expenses, this discrepancy has inflicted predictable damage on the bonds.

In 2009, the monorail estimates it generated $27.6 million in total revenue, which includes advertising sales and revenue from some other minor sources. It incurred $22.6 million in operating expenses.

That leaves net revenue — the sole source of repayment — of $5 million. The system’s cost to repay debt in 2009: $34.4 million. The company expects $4.8 million in net revenue next year. It faces $37.4 million in interest and principal due on bonds.

In a report over the summer, Fitch Ratings attributed the insufficient ridership to an “extremely constrained” economy, along with passengers’ resistance to fare hikes and the system’s failure to establish marketing partnerships with casinos.

The company has failed to replenish its fund dedicated to repaying debt every month since January 2008, Wells Fargo said.

On Jan. 1, $16.8 million in principal and interest owed to the top-tier bondholders came due. With no cash available to make the payment, the trustee obtained the money from Ambac.

Owners of the uninsured second-tier and subordinate portions are not being repaid. About $5.5 million in principal and interest on those bonds came due Jan. 1.

Bondholders should not expect the money, Wells Fargo said. They should not expect it on the next coupon and maturity date in July, either. The $3.7 million in interest the monorail failed to honor in July last year remains unpaid.

Fitch does not expect the monorail to generate enough revenue to repay bondholders beyond this year.

Bondholders in the top tier are yet to miss out on a payment because of the insurance proceeds from Ambac. The bond market, though, does not seem to attribute much value to a defaulted bond covered by an insurance policy from an insurer with a dubious future at ratings of Caa2 and CC from Moody’s Investors Service and Standard & Poor’s, respectively.

Late last month, one of the top-tier bonds maturing in 2032 traded at a price of 22 cents on the dollar.

Already missing payments, the uninsured bonds in the second tier are trading at even lower prices. One of the second-tier bonds maturing in 2028 traded in mid-December at a price of just 10 cents on the dollar.