When the Federal Reserve began expanding its balance sheet with quantitative easing, it was seen as an emergency measure. Yet a decade later, the Fed is again in jeopardy of hitting zero lower bound and its balance sheet remains large.

Berenberg Capital Markets Chief Economist for the U.S. Americas and Asia Mickey Levy worries “the Fed has boxed itself in by trying to do much and now has an unhealthy relationship with the markets, where the markets expect the Fed to do too much." Speaking at the Shadow Open Market Committee meeting held Friday, Levy said, the Fed “needs to step away from its clear easing tint.”

In fact, one question at Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference after the emergency cut dealt with raising rates if the effects of COVID-19 on the economy did not match expectations, and the chair said the panel “won’t hesitate” if it’s appropriate. Levy said he is concerned “when the virus fears pass, the Fed will not take away the cuts.”

The Fed has expanded the role of monetary policy and its toolkit since the financial crisis.

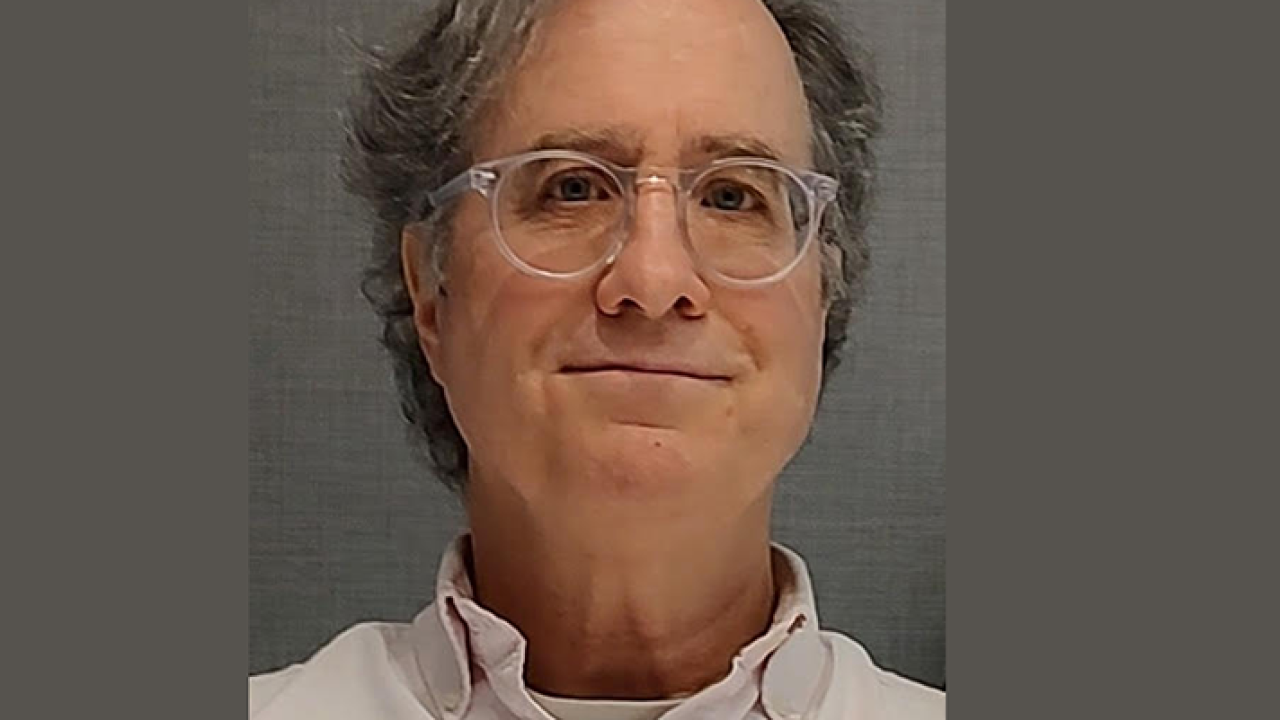

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President Esther George, also speaking at the SOMC meeting, under the auspices of the Manhattan Institute, addressed her concerns about the Fed’s large balance sheet and its independence.

She said, “the use of negative interest rates gives me pause as a way to address a future encounter with the effective lower bound,” and noted “the potential side effects of balance sheet policies that pose risks to financial stability and threaten the central bank’s policy independence.”

Going back to 2013, George was concerned about quantitative easing, since “financial markets were stable and the economy was growing.” Noting the meeting was a tribute to Marvin Goodfriend’s influence on monetary policy, she added, “These concerns about the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet under those conditions echoed many of Marvin’s concerns. In my view, the possible unintended side effects of the ongoing asset purchases posed risks to economic and financial stability and served to unnecessarily further complicate future monetary policy.”

While “conventional wisdom” suggests asset purchases were basically favorable, “it remains less than clear to me that the longer-run costs of balance sheet policies have been fully taken into account,” George said.

Some consequences she pointed to included the need for the Fed to re-evaluate its operating framework. “Given the abundant reserves associated with its balance sheet policies, the FOMC had to consider whether the federal funds rate target could be achieved administratively by setting the interest rate on excess reserves.”

And when the Fed tried to shrink the balance sheet, “it proved challenging to gauge the minimum reserve balances needed for achieving the federal funds rate target without intervention by the open market desk at the New York Fed,” she said. “As a result, the desk resumed regularly conducting repo operations and outright purchases of Treasuries to build a bigger buffer and ensure an ample supply of reserves. These operations have caused some confusion in markets as some participants have seen them — incorrectly, in my view — as a type of quantitative easing.”

And the large-scale asset purchases helped raise asset valuations, which could lead to a bubble that would threaten economic health, she noted.

“Another concern I share with Marvin is the risk that income from the Fed’s large balance sheet combined with our capital surplus could tempt fiscal authorities to view the Fed as a source of funding for government programs,” George said. “I would argue that we have seen a degree of this risk unfold. The funding of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), as required under the Dodd-Frank Act, is a case in point. Each quarter the Reserve Banks transfer to the CFPB, without Congressional appropriations, the amount of funds requested by the Director of the CFPB to carry out its operations. To date, the Federal Reserve has transferred almost $4.4 billion to the CFPB.”

Dodd-Frank Act made the Fed responsible for two years of funding for the “Office of Financial Research in support of the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC),” she said.

The Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act was, in part, funded “by reducing the Federal Reserve Bank stock dividend rate for member banks with assets of more than $10 billion,” and capped Fed aggregate surplus funds at $10 billion, with excesses “transferred to the Treasury general fund,” she said. “The potential policy implications of modifying dividends to member banks, or more generally, the requirement for member banks to purchase stock in a regional Federal Reserve Bank, is a concerning development that risks undermining the Federal Reserve’s long-standing institutional design of public and private interests serving the American public.”

The Fed’s holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities “arguably blur the line between monetary policy and credit allocation.”