SAN FRANCISCO — Two groups gathered in the San Francisco Bay Area this week to discuss municipal bonds, public budgets and interest rate swaps.

They talked right over each others’ heads.

The Service Employees International Union — representing some of the region’s lowest-paid public employees — rallied in Oakland to demand that local governments stop making payments on interest rate swaps that they say are costing them jobs.

Municipal bond investors and analysts, who met across the bay in San Francisco Wednesday at Bloomberg LP’s first municipal finance conference, worried aloud about whether local governments would have the nerve to fire enough workers to balance their shrinking budgets, but didn’t mention bank forgiveness as a solution to local budget woes.

The gap between Wall Street and Main Street was on full display.

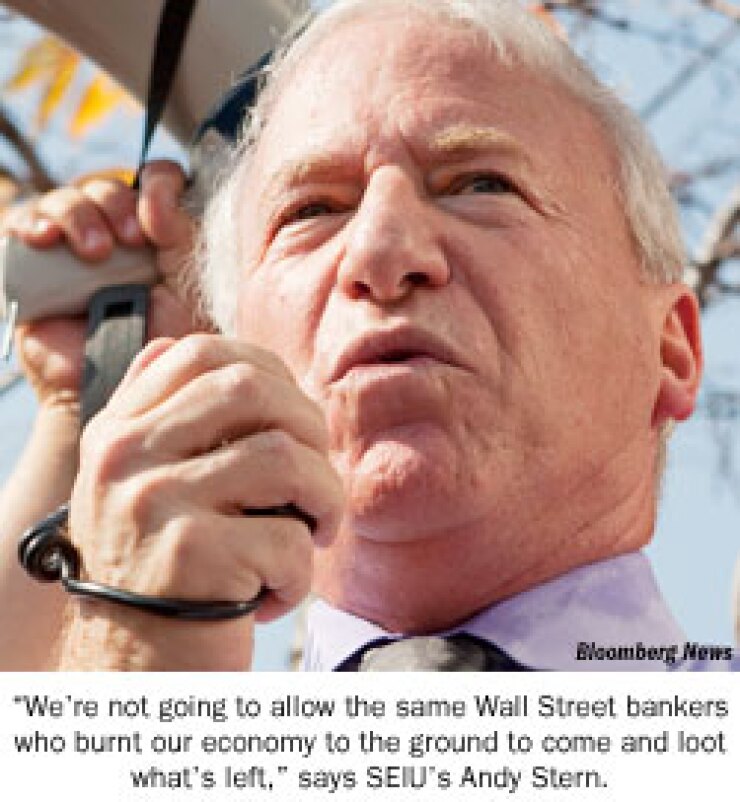

“We’re not going to allow the same Wall Street bankers who burnt our economy to the ground to come and loot what’s left,” Andy Stern, president of the two-million member SEIU, said at the rally at Oakland City Hall. “It’s time for Wall Street CEOs to stop putting their companies before the good of our country and end these deals that are bleeding our communities dry.”

The SEIU brought its “Stop the Swaps” campaign to Oakland after a victory last week in Los Angeles, where the City Council ordered the city administrative officer to renegotiate two swaps that elected officials and the SEIU said are rip-offs. The union says it has identified another $150 million of swap payments it would like to see banks forgo in the Bay Area.

Municipalities for years have used interest rate swaps to hedge their exposure to floating-rate debt they have issued. But during the credit market meltdown many swaps became unprofitable for the issuers and some have been forced to pay large sums to counterparties in order to terminate them.

The labor rally featured a bullhorn, speeches from local politicians, testimony from local workers struggling with layoffs and foreclosures, and a march on the local Citibank branch with signs reading “Wall Street Should Pay, Not the Bay.”

At the public finance conference across the bay, the speakers — wearing sleek, wire-thin “Madonna” headsets on a stage set with white modernist furnishings — talked about net present values, matching of assets and liabilities, and disclosure. Bloomberg Television anchor Cris Valerio pushed the speakers to keep the excitement level up, but she didn’t have quite the same raw material to work with as Andy Stern.

Like all good public finance conferences, the discussion included a spirited debate about the muni swaps and whether they’re being sold to unsuspecting, naïve municipal officials. Swaps have plenty of detractors and defenders in the market.

“The swaps didn’t unwind. It’s the variable-rate bonds that unwound. It’s the auction-rate securities market that fell apart. That’s where the problem was,” said John Knox, a bond lawyer at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP. “The focus here is on the swaps because maybe it’s hard to understand or because it looks like big numbers, but that’s not really where the problem is.”

Knox traced the problem back to the failure of the bond insurers, which caused variable rates on insured debt to skyrocket and stop working even though the attached swaps were still functioning as intended.

Swap critics like Christopher “Kit” Taylor, former executive director of the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, said municipalities and the bankers selling them swaps should have seen that risk coming.

But risk management is not what the SEIU is talking about. The union isn’t arguing that Los Angeles’ swaps are broken or that the city was duped.

Los Angeles debt manager Natalie Brill says the City of Angels’ plain-vanilla swaps are working as planned. The city used the swaps to synthetically fix the interest rate on $313.8 million of variable-rate wastewater enterprise fund debt. Officials wanted to avoid big swings in its interest payments, so it agreed to pay a fixed rate of 3.34% to Dexia Credit Local and Bank of New York Mellon in exchange for 64.1% of the one-month London Inter-Bank Offered Rate.

The rate on the variable rate the city is receiving closely tracks the variable rate it’s paying. As of June 30, 2009, the difference between the two rates was less than one basis point. If Los Angeles terminated the swap, it would owe the banks $26 million, but it has no pressing need to terminate. On average, over its 30-year life, Brill still expects the transaction to yield savings.

That’s little comfort to SEIU workers who are losing their jobs today.

“We’re not saying cities should break any contracts” unilaterally, said Saqib Bhatti, a SEIU researcher who has been digging through city financial reports like a muni analyst. Instead, he thinks banks have a moral obligation to renegotiate their swap contracts now that rates have fallen below what could have ever been expected when cities agreed to them.

“The taxpayers are the reason these banks are still around,” he said. “And the banks are the reason the Federal Reserve had to cut interest rates so low.”

In Oakland, that means forgiving a swap the city took out in 1998 and renegotiated five years later. Oakland took a $5.975 million upfront payment in 2003 as part of a deal under which it pays Goldman Sachs Mitsui Marine Derivatives Products a fixed rate of 5.6775% for 65% of one-month Libor. The city defeased the underlying debt in 2005 but still has a swap with a notional value of $85 million outstanding.

Oakland is paying about $5 million a year to service the agreement, and it is currently struggling to decide which city services need to be cut to close a $4.8 million budget gap.

“We as city employees have taken furloughs, pay cuts, and layoffs to keep our city afloat,” said SEIU member and city employee Al Marshall. “Now we learn Wall Street banks are pimping the city for $5 million a year. They get this money without doing absolutely anything.”

He says city workers have renegotiated enough to save the city money. It’s time for other creditors to give.

Back in Los Angeles, Brill is trying to come up with her best pitch for the city’s counterparties, while insisting to the broader muni market that the city is still a good credit risk.

“We’ve been instructed by the council to go and talk to the banks. That’s what I’ll do,” Brill said. “The city of L.A. has a contractual obligation, and contracts are negotiable. We will continue to deal with the banks in good faith as we always have.”

In the meantime, the SEIU will be taking its swap protests on the road. Bhatti said the union is still deciding where to go next, but is looking at deals all over the country.