Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

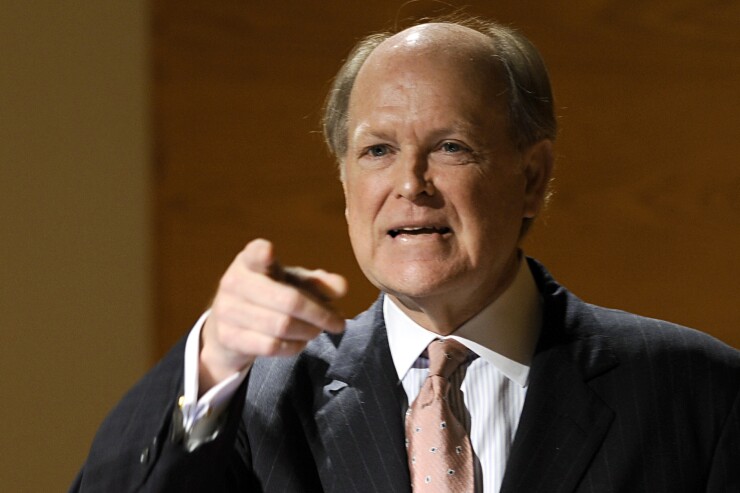

The Federal Reserve should return to its precrisis corridor operating system, with a smaller balance sheet where the fed funds rate is set slightly higher than the interest paid on reserves, former Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia President Charles Plosser said.

“The Fed hasn’t addressed the consequences of a large balance sheet,” he said.

Quantitative easing “flooded the system with reserves,” Plosser said Friday at a Shadow Open Market Committee meeting. With a large balance sheet, the Fed is tied to a “floor system,” where the central bank, by setting a rate on bank reserves, sets “a floor for short-term risk-free rates.”

This creates an issue since the Federal Open Market Committee, which is responsible for monetary policy, is not controlling the interest paid on reserves, which is set by the Board of Governors.

“Who decides the balance sheet size?” Plosser asked. “Is it the FOMC or the Board of Governors?”

He added, “My view is that it would be a huge mistake to adopt a floor system without addressing this governance issue in legislation.”

With a bloated balance sheet, fed funds trading has thinned, he said. Additionally, “an operating regime where the Fed’s balance sheet is unconstrained as to its size or holdings is ripe for misuse, if not abuse,” Plosser said. “A Fed balance sheet unconstrained by monetary policy becomes a new policy tool.” And it damages the Fed’s independence.

Political pressure or even Congressional mandate could be used to force the Fed “to manage the portfolio for political ends.” For example, the Fed could be directed buy securities to bail out a municipality on the verge of default, Plosser warned. Of course, if the Fed were to be limited to an all-Treasuries portfolio, this wouldn’t be an issue.

Plosser also questioned the notion that a large balance sheet makes monetary policy more accommodative. “How does this accommodation come about?”

The case for using a floor system, Plosser said, is “not convincing.” He added, “The Fed is doing itself a disservice opening the door for more flexibility. Removing constraints opens the door to failure of independence.”

Plosser said the Fed needs to conduct policy more systematically and “specify its end game.”

The FOMC currently “draws an unnecessary distinction between monetary and balance sheet policy, while masking the more important one between monetary and credit policy,” according to Peter Ireland, a professor of economics at Boston College, who appeared on the same panel as Plosser. “It requires the Fed to operate with a balance sheet that is unnecessarily large, and perversely limits the continued effectiveness of open market operations at zero lower bound.”

By defining policy actions as those “taken to manage the supply of base money to stabilize the aggregate price level,” he said, “the FOMC would emphasize that those actions remain effective and are intended to achieve the same goal, regardless of the level of short-term interest rates.”

This works, Ireland said, when the Fed uses fed funds rate targeting or quantitative easing. By “making monetary policy as predictable and easily understood as possible, central bankers can remove uncertainty about their own actions as a source of instability and allow relative prices to adjust as quickly as possible to help the economy respond efficiently to shocks of other kinds.”

The SOMC meeting, under the auspices of the Manhattan Institute, focused on Fed communications and its balance sheet.