A legal battle over charter school funding in Palm Beach County may have implications for public education in the entire state of Florida.

On Feb. 24, the Florida Fourth District Court of Appeal ruled that the Palm Beach County School District was in violation of state law by excluding the charter schools in its district from getting any share of the money raised by a voter-approved tax.

Florida state law says charter school students will be funded "the same as students enrolled in other public schools in the school district.”

In 2018, voters in Palm Beach County approved a one-mill, five-year property tax hike to pay operating expenses only for the district's traditional public schools; the referendum’s wording specifically excluded charter schools.

After it passed, two charter schools and the parents of a charter school student sued the district seeking a share of the tax revenue.

The school district prevailed in the local circuit court, and won an appeals court ruling in April 2020.

The charter plaintiffs requested that the 2-1 ruling be heard en banc, by all the appeals judges in the Fourth District, and they overturned the earlier decisions and, by 7-4,

Charter schools enrolled about 21,400 students in Palm Beach County, according

While the decision affects the 72,750 charter school students in the Fourth Appellate District, there are over 194,000 charter school students in 19 other counties in Florida where a similar tax is in place.

“Given the far-reaching implications of the panel’s decision on charter school students across the state, ongoing litigation involving the very same issue, and the varied conclusions of five reviewing judges in three separate suits, this case is exceptionally important,” the court ruling stated.

The court pointed out that there are two pending lawsuits in the Eleventh Judicial Circuit of Florida related to a school board operating millage approved by voters in Miami-Dade County from which charter schools have also been excluded and added that other litigation was very possible.

“This decision will also likely have a major impact on future charter school funding cases,” the court ruling said. “The majority’s interpretation of the opening sentence of section 1002.33(17), Florida Statutes, erodes a guiding principle established by the Legislature that charter school students be funded the same as their counterparts attending district schools.”

The school district may appeal to the state Supreme Court. The February ruling certified it to the state's high court that the dispute is a "question of great public importance."

According to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, Florida has the third-highest number of charter schools and enrollment after California and Texas.

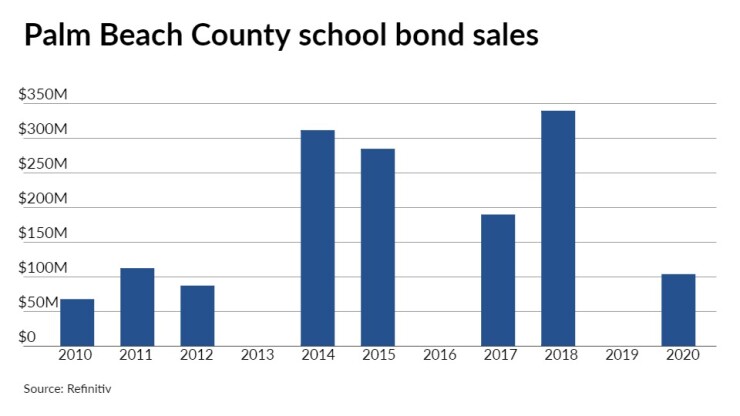

Since 2010, the Palm Beach County School Board has issued about $1.5 billion of debt, with the most issuance coming in 2018 when it sold $340 million.

Palm Beach County schools have a general obligation bond rating of Aa2 from Moody’s Investors Service with a stable outlook. Moody’s also rates the district’s short-term notes MIG-1 and assigns an Aa3 rating to the long-term certificates of participation. The GOs and COPs are rated AA by S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings, which also assigned stable outlooks to the credit. S&P and Fitch don’t rate the district’s short-term notes.

S&P told The Bond Buyer on Tuesday that it was monitoring the credit situation closely.

“As of March 9, S&P Global Ratings maintains 12 public ratings on Florida charter schools. While none of these rated schools are in Palm Beach County, we are aware of the recent judgment which favored Palm Beach charter schools pertaining to a 2018 voter-approved property tax increase to fund operational items such as campus safety and teacher pay increases," said Shivani Singh, director in S&P's charter school group. "We understand school districts are currently not sharing these voter-approved property tax dollars with charter schools in counties such as Miami-Dade."

In a report issued in late 2019 on Florida charter schools, Singh wrote that state law requires charter schools be funded on par with other public schools throughout the state and that charter schools are entitled to their proportionate share of categorical federal and state program funds.

"Despite statutory provisions, the inequity in funding between charter and public schools persists. This is due to differentials for operational and capital funding between public and charter schools," he wrote in the report.

There are 48 school district authorizers in the state and S&P reported that all of its rated charter schools were authorized by boards of school districts in which they operated.

“In our view, the prevalence of school district authorizers typically comes with an inherent conflict of interest and tension due to competition for students and the associated per pupil state funding,” Singh said in the report. “However, most of our rated charter schools in Florida report a good working relationship with their respective authorizers and some benefit from good authorizer support in the form of financial backing for capital projects and equipment purchases in the form of millage levies.”

The majority of Florida charter schools S&P rates (78%) are investment grade compared to 44% for the rated charter school sector as a whole nationwide, S&P said. Many charter schools have issued non-rated bonds.

Singh said the ruling could help the bottom line of charter schools.

"In our view, future judgments that result in increased operational dollars to charter schools could alleviate expense pressures given some schools continue to self-fund these teacher pay raises. We will monitor credit ramifications for our rated charter schools,” Singh said Tuesday.

Moody’s said in a report last week that while its ratings for Palm Beach County schools remain unchanged, the court’s ruling was a credit negative for the district.

Moody’s said that because of the decision the Palm Beach County district will now have to share with all charter schools in Palm Beach County about $22 million a year through fiscal 2023.

“The lost funds are equal to only about 1% of the Palm Beach district's fiscal 2020 operating revenue, but the gap will still have to be closed, possibly through cuts,” Moody’s said in is report.

Some of the cities in Palm Beach County include Boca Raton, Boynton Beach, Delray Beach, Jupiter, Palm Beach, Palm Beach Gardens, North Palm Beach and West Palm Beach.

Remaining undecided is what happens to the revenue collected for the first two years of the five-year tax. The appeals court did not take up the question because the circuit court had not considered it. "We remand for the circuit court to conduct any necessary hearings, evidentiary or otherwise, to determine this issue through findings of fact and conclusions of law in the first instance," the ruling said.

In the United States, local school district spending is mostly financed by local revenue from property taxes and by state government appropriations.

This makes school spending susceptible to both state and local income shocks, according to the Municipal Finance Conference.

This has been especially true during the latest shock, the COVID-19 pandemic.

“With a state-wide income shock, all districts see a decrease in state aid, and the overall reduction in school spending is larger than what results from a local shock: a 10% statewide decline in income would lower spending over the following 13 years by 7%,” the group said.

Based on a

The Municipal Finance Conference consists of members from Brookings’ Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, Brandis’ International Business School’s Rosenberg Institute of Global Finance, the Washington University in St. Louis’ Olin Business School and the Harris Public Policy at the University of Chicago.