This is no longer a reversal of the flight to quality. Municipal bonds are flat-out weak.

Stung by illiquidity and thin demand, tax-exempt bonds sold off Wednesday by four basis points at all maturities from five to 20 years, according to the Municipal Market Data scale.

At 3.15%, the 10-year triple-A municipal yield has now surged 24 basis points in the last 10 trading days.

The early stages of this updrift in yields could be described as an unwinding of the flight to safety that bolstered municipals earlier in the month. Investors sought the safe haven of Treasuries and other high-quality dollar-denominated bonds in the aftermath of the earthquake in Japan and the civil unrest in North Africa and the Middle East, pulling yields down.

As that play retrenched, yields climbed back up.

People aren’t talking about a flight-to-quality reversal anymore. They’re talking about illiquidity, thin demand, and an inability to digest even an extraordinarily light amount of supply.

“It doesn’t seem like the bid side’s very strong,” a trader in New Jersey said, citing “loads and loads” of bids wanted.

Bondholders were seeking bids on $800 million of municipal bonds yesterday, according to a Bloomberg LP index.

One trader in Chicago pointed out that MMD, in one of its intraday reads, pushed yields on its scale up by four basis points for 10-year maturities almost as soon as the market opened. That freaked people out, the trader said, because nobody wants to have to mark down the value of inventory just as the quarter is ending.

The unease showed in the pricing of the day’s biggest deal, the Florida Board of Education’s $175 million sale in the competitive market, with the winning bid coming from Bank of America Merrill Lynch. The 2020 maturity of that deal priced at 3.48%, or about 50 basis points above the triple-A scale.

“All of a sudden they’re backing their bids off,” the trader said. “It’s self-determining. ... It was kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Maybe so, but we would argue that if MMD’s guess at weaker bonds can trigger bonds to weaken in real life — this during an extreme supply drought, mind you — that speaks volumes about how vulnerable the market is.

Pension plans

Today we resume our category-by-category analysis of the demographics that purchase, or don’t purchase, long-term municipal bonds. Our concern is that long-duration tax-free debt appears unsuitable for each demographic, either because it can’t benefit enough from the tax exemption or because it is too averse to inflation and interest rate risk to take on significant duration.

Our next demographic is pension plans, which are a go-to buyer for long-duration debt worldwide.

Between corporate and government sponsors, pension plans hold nearly $10.5 trillion of assets, according to the Federal Reserve.

Actually, this doesn’t portray the complete sum of money pension plans are capable of extending to borrowers. There’s often nothing keeping foreign pension plans from converting their local currencies into dollars, and buying dollar-denominated bonds.

A Towers Watson study found that at the end of 2009, the biggest 13 pension markets alone held $23 trillion of assets.

Pension funds are dollars invested today with the intention of meeting future retirement payments for workers.

Like insurance companies and banks, pensions are striving to match the duration of their assets with the duration of their liabilities.

The goal is to render the pension liabilities indifferent to swings in interest rates, because any lurch in rates would exert the same influence on the assets as on the liabilities.

The retiree payouts pensions expect to make in the future often represent very long-duration liabilities. Sometimes workers in their 20s and 30s have already accrued benefits that won’t be paid out until these workers are in their 60s and 70s.

Citigroup maintains a pension liability index with a duration of 16. BNY Mellon maintains a number of pension liability indexes ranging in duration from 8 to 17, and describes a “typical” plan’s liability duration at 13 years.

A Fitch Ratings report earlier this year found that liabilities for most public pension funds in the U.S. show duration of roughly 10 to 12.

That makes long-duration, long-maturity debt a logical holding for many pension plans. Indeed, pensions exhibit ravenous appetite for duration.

A French energy company called GDF Suez earlier this month sold a 100-year bond in euros, and pension funds reportedly bought 60% of the deal.

An advisory panel to the Treasury Department in February suggested the federal government should sell 100-year bonds to tap demand for long duration from, among other types of investors, pension funds.

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, which with $224 billion is by far the biggest municipal pension system in the U.S., holds one segment of its portfolio in securities with an average duration of 42 years.

Considering how steep the tax-exempt yield curve is, municipalities could use access to this demand.

The average duration of bonds in the $1.2 trillion S&P/Investortools Municipal Bond Index is 6.7 years, and the average duration appetite for banks and insurance companies is often significantly shorter than that.

Unfortunately, pensions’ appetite for duration helps municipalities not at all. Nearly all income pension plans earn is exempt from taxes.

They therefore seldom invest in tax-free bonds because the yields aren’t high enough to compete with untaxed rates paid on taxable bonds.

We’ll also lump foundations and endowments into this category. Foundations and endowments typically have perpetual investment horizons — perfect for long-duration investing. They also are exempt from most kinds of taxes, for the most part clearing them out of the market for tax-free bonds.

College endowments in the U.S. and Canada manage about $350 billion of assets, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers, and according to the Foundation Center the biggest 100 foundations in the U.S. hold $225.7 billion of assets.

Now that we have your attention

While we’re on the topic of pension plans, though, we wanted to use this opportunity to do something nobody has done for about two years: deliver some good news about state retirement funds.

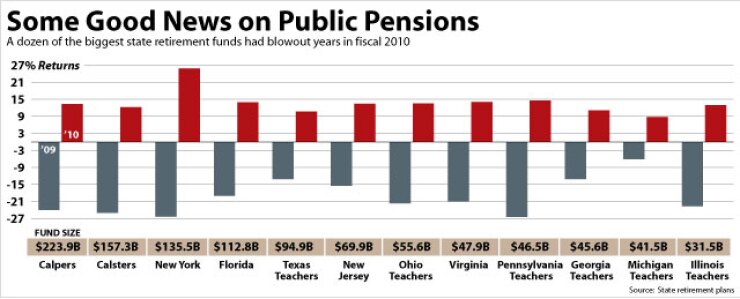

The annual reports for state pension plans are in, and their investment results in fiscal 2010, which for most states wrapped up at the end of June, were excellent.

We looked at a dozen of the biggest state funds, with combined assets of more than $1 trillion, and found a weighted average return of 14.4%.

The median return on public pension funds with at least $1 billion in assets swung to 13.1%, from the devastating 18.8% decline the previous year, according to Wilshire.

This comes just as a number of plans, such as Illinois, New York, Virginia, and Colorado, have slashed the assumed return on investments over time.

The good news comes with a barrage of caveats.

Foremost, the investment income last year wasn’t nearly enough to overcome the investment losses from a year earlier. We tabulated $133.6 billion in investment income for the 12 funds we looked at, versus a $252.4 billion loss in fiscal 2009.

Two, these results will not improve funding ratios in most cases, because funding ratios measure assets and liabilities actuarially.

Funds assume a given return every year and stick deviations from this return in the footnotes. In most cases, the returns from 2010 will not be counted among the actuarially assumed assets used to calculate funding ratios.

We also wanted to emphasize that funds did so well not because the people running them are wizards, but because markets in general did well.

The Wilshire 5000 Index, which measures most stocks in the U.S., surged 15.7%. Barclays’ high-yield corporate bond index vaulted 26.8%.

Some public pension funds didn’t even beat the 12% return delivered by long-term Treasuries.

Still, considering the commentary on public pensions lately has ranged from “they’re in deep trouble” to “they’re the single gravest threat to mankind,” we figured we’d highlight some encouraging news for once.

Corporate taxes

A nifty piece of reporting from the New York Times last week found that General Electric paid zero taxes on its $14.2 billion of profit last year.

We’re not going to wade into the controversy that has ensued over this assertion, but something else in the article piqued our interest: taxes on corporate profits contributed 30% of all federal revenue in the mid-1950s. Today, they contribute 6.6%.

The Census Bureau posted state and local government tax receipt data for the fourth quarter earlier this week, allowing us to satisfy our curiosity about whether corporations’ contribution to municipal revenue has undergone a similar decline to the one seen at the federal level.

It has, sort of.

Corporations paid $45.5 billion in taxes to states and localities in 2010, the lowest corporate tax intake since 2004.

Municipalities’ corporate tax receipts last year sank 5% despite a 37% surge in corporations’ pretax profits to $1.24 trillion, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the second-most profitable year in history for U.S. companies.

Corporate taxes contributed 3.5% of municipal tax revenues in 2010, according to the Census.

The contribution of corporate taxes to municipal tax receipts has been declining pretty steadily since the late 1970s, according to Census data. In 1979 and 1980, corporate taxes represented more than 6% of state and local government tax revenue.

To be fair, though, corporate tax contributions to municipal revenues are at a similar share today to the share seen in the 1960s.