States have been hit with a slew of negative credit outlooks as they struggle with the weakest economic recovery in 40 years.

As of Tuesday Moody's Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings each had negative outlooks on 10 states, meaning they are at risk of downgrades in the next two years. S&P had an 11th state – Kansas – on negative credit watch, signaling a potential downgrade within six months.

States are paying the price for meager U.S. growth since the end of the Great Recession, an oil price plunge, and an aging population that raised the cost of health and retirement benefits.

"The 'new fiscal reality' is an environment where revenues are not rising as quickly as they have in the past but expenditure demand is escalating faster than historical experience," PNC managing director Tom Kozlik wrote in an email this month.

Aside from Kansas, Alaska, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania all had negative outlooks from both S&P and Moody's. S&P also had New Mexico, Massachusetts and Wyoming on negative outlook, while Moody's had North Dakota and West Virginia.

Fitch Ratings had no negative outlooks but one state – Alaska – on credit watch negative. Fitch had a lower rating on one state – Illinois – that S&P gives a negative outlook to, and doesn't rate four states that are on the negative outlook list of at least one of the other agencies.

As of Tuesday, Moody's had two states on positive outlook, S&P had three, and Fitch had zero.

This calendar year through Tuesday S&P had downgraded three states and upgraded none, Moody's had downgraded two and upgraded one, and Fitch had downgraded one and upgraded none.

Robin Prunty, S&P managing director for U.S. Public Finance, said in March that the number of states with negative outlooks was very unusual given that the country was in the sixth year of an economic recovery.

At heart the states' financial weakness can be traced to the listless economic recovery, said Gabriel Petek, S&P's sector leader for U.S. states. Inflation-adjusted U.S. gross domestic product growth hasn't hit a 3% rate since 2005.

The slow recovery is partly due to unusually low labor productivity growth, Petek said. "Labor productivity growth, at 1.2% annually, is tied with the 1973-1979 period for the slowest growth rate through a business cycle since 1943."

S&P also estimates the continuing retirement of the Baby Boom generation has shaved about 0.6% from the U.S. growth rate and may take 0.8% in the coming years.

The slowness of the economic recovery has led to a comparatively slow rebound for state revenues. By the second quarter of last year 29 states had at least as much inflation-adjusted revenue as they did in their pre-recession peaks, according to the "Fiscal 50" report by the Pew Charitable Trusts. By comparison all states except for Michigan had recovered to pre-recession revenue levels six years after the 2001 recession, Pew stated.

"State revenues reflect what is going on in the economy," Fitch managing director Laura Porter wrote in an email. "As the economy has recovered – slowly by historical standards – so have state revenues."

According to statistics compiled by Merritt Research Services President Richard Ciccarone and The Bond Buyer, in some important respects the states still have not recovered their pre-recession highs. In 2015 dollars the median governmental activities revenue per capita peaked in fiscal year 2007 at $2,610. It fell to $2,322 in fiscal year 2010 and returned to $2,567 in fiscal year 2015, the most recently available fiscal year. By this measure, the states are still about 1.6% behind their pre-recession peak.

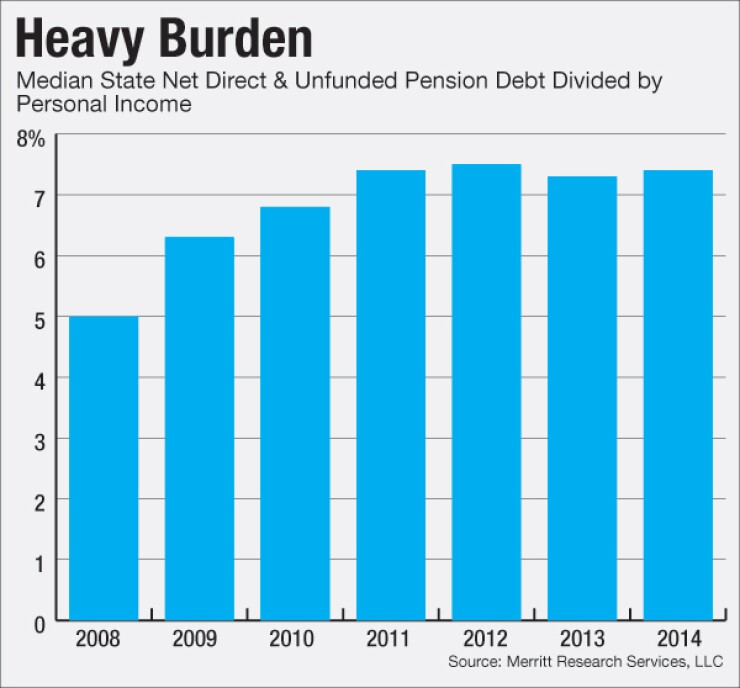

Other measurements from Merritt show a more serious deterioration. State net direct debt plus state unfunded pension liabilities as a percent of state personal income increased to 7.4% in 2014 from 5% in 2008. The state pension funding ratio declined to 70.7% in fiscal 2014 from 83.5% in fiscal 2008. More dramatically, unrestricted net assets as a percent of state governmental activities expenditures slid to negative 17.3% in 2015 from negative 2.4% in 2009.

"The unrestricted net assets position is a better long term gauge to measure financial condition [than] the traditionally used fund balance since it takes into consideration long term liabilities like unfunded pensions, other post-employment benefits, operating and cumulative deficits," Ciccarone wrote in an email. "Debt used for specific infrastructure projects is excluded to the extent that it is offset by related infrastructure assets."

This measure's deterioration is partly due to a Government Accounting Standards Board accounting change that went into effect in 2015 that required inclusion of pension liabilities that had accrued before 1997, something that had previously been excluded.

According to S&P, states are being hit by particular spending demands as well as unusually slow growth in revenues.

"Increasing pension and entitlement spending has reduced fiscal capacity for economic growth-oriented spending," S&P managing director Robin Prunty wrote May 10. In "U.S. State Budget Outlooks Heading into Fiscal 2017 Are All over the Map," Petek estimated that the trend-line for entitlement benefits as a percent of state expenditures ballooned to nearly 40% in 2013 from 32% in 1995. In the same period, Petek estimated that capital outlays declined to 6% of state expenditures from 7.1%.

Not all the negative outlooks are due to country-wide factors. Widespread drilling for oil earlier in the decade led to a surplus supply, lowered its price in 2014 and hurt the finances of several energy producing states. The decline in the price of oil has contributed to negative outlooks on Alaska, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

Unfortunately for those who hold state bonds, the immediate future may hold more difficulties. "Revised revenue forecasts for fiscal 2016 and projections for fiscal 2017 indicate a generally slower overall revenue environment relative to performances in recent years," Petek wrote in late April.

In the Rockefeller Institute of Government report "Softening Third-Quarter Growth in State Taxes, Weak Forecasts for Fiscal 2016 and 2017," released in March, Lucy Dadayan and Donald Boyd wrote that they expected much less revenue growth in fiscal 2016 and 2017 than in fiscal year 2015.

"S&P Global Ratings' long-term (approximately 10 year horizon) economic growth forecast is at roughly 2.0%," Petek wrote in an email. "In general, state taxes are levied against current economic activity—such as wages and consumption. We think it's reasonable to expect the growth rate of a state's recurring revenue base to exhibit a similarly muted rate of growth."

The states may be running out of time to put their houses in order before a new recession strikes. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the average U.S. post-World War II recovery duration has been 65 months. The current economic recovery has run 83 months.