WESTPORT, Conn. – As Connecticut strives for long-term solutions to its economic ills, a restructuring expert says in-kind contributions of real-estate assets could creatively tackle the state’s steep pension liability problem.

Michael Imber, a managing director with EisnerAmper LLP, said momentum is building for such a strategy, which he said could “meaningfully increase Connecticut’s funding ratio.”

Authors of a far-reaching

According to the Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Growth, Connecticut could benefit from evaluating the in-kind contribution of assets of land, buildings, airports, roads, healthcare facilities and other assets that the state does not need to own and which may have valuable development potential.

It could improve pension-funded ratios and lower annual required contributions, the report said.

Connecticut, in the crosshairs of bond-rating agencies for myriad reasons, has roughly $34 billion in underfunded pension obligations -- $21 billion to the State Employees Retirement System and $13 billion to the Teachers' Retirement System. Its five largest cities, including capital Hartford, owe a further $2.1 billion.

State legacy liabilities are “precariously high and trending higher,” said the fiscal stability panel, which Gov. Dannel Malloy appointed. It consists of 14 business leaders “with different hot buttons,” said James Smith, Webster Bank chairman and former chief executive, who co-chaired the panel with Robert Patricelli, the retired CEO of Women’s Health USA.

“The ship of state is burning and we have little wind in our sails,” Smith told a joint meeting of the General Assembly’s committees on appropriations, commerce, planning and development, and finance, revenue and bonding at the state capitol in Hartford.

The committee's March 1 report estimated total state liabilities at $87 billion as of last June 30. That includes general obligation and non-GO debt, unfunded pension and unfunded other post-employment benefits.

“These liabilities, as well as the annual payments required to service them, are extremely high relative to other states,” said the report.

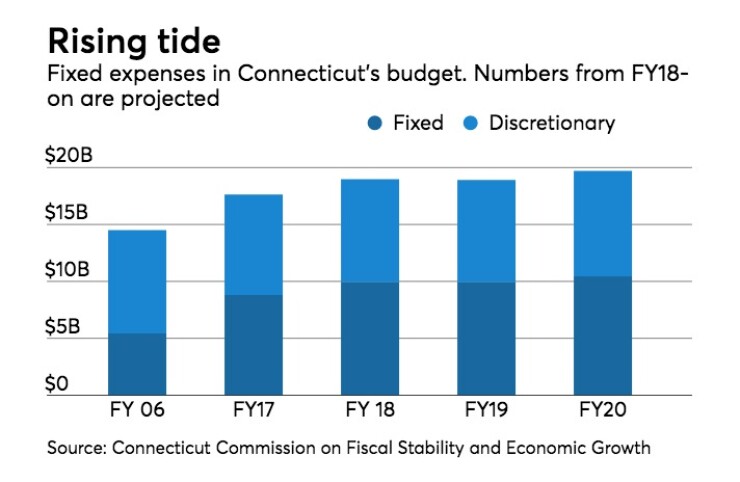

According to Imber, those liabilities effectively crowd out other priorities in state and municipal budgets.

“The commission should be commended for thinking creatively about attacking pension underfunding,” said Imber, who advised major creditors during the bankruptcy cases of Detroit, Jefferson County, Ala., and Mammoth Lakes, Calif.

“Under independent professional management, these assets can be deployed to stimulate the economy and incentivize the legislature to create an environment geared for growth, further increasing the funding ratio.”

Pension contributions for the TRS and SERS are projected to spike from $2.7 billion in fiscal 2018 to $4.7 billion in fiscal 2032, representing a compounded annual growth rate of 4%.

The state’s $41.3 billion fiscal 2018-19 budget called for the establishment of the Connecticut Pension Sustainability Commission. That panel, consisting of 13 members when fully staffed and appointed by various political higher-ups including the governor and House and Senate leaders, must submit its findings by year’s end.

It would perform a preliminary inventory of state capital assets to determine “the extent and suitability of those assets for including those assets for inclusion in such a trust”; study their potential for minimizing unfunded liability; and recommend on the appropriateness of such a move and the steps necessary to establish a trust.

“Connecticut state leaders have expressed interest in the potential for in-kind asset contributions as part of the solution for pension underfunding,” said Imber. “The new Connecticut Pension Sustainability Commission’s task in 2018 is to evaluate that potential.”

The panel, however, has been slow out of the starting gate with only four members in place.

Imber recommends a legacy obligation trust model, through which the trust would issue certificates of trust akin to stock shares and divide them among pension funds. The government unit would receive a credit against its unfunded liability based on asset valuations. A rising pension funding ratio could effectively reduce catch-up payments.

Urban planner and book author

"This is not an unusual way of solving a pension deficit, say within a corporation,” Detter said from Stockholm.

"The transfer price is essential and also, just selling off the assets once inside in the pension fund is not optimal,” said Detter, co-author with Stefan Fölster of the book, “The Public Wealth of Cities: How to Unlock Hidden Assets to Boost Growth and Prosperity.”

"That would leave a lot of money on the table. Ideally you would like to create a vehicle that has the capacity to develop the assets over time,” said Detter. “Hence, the devil is in the detail of the governance of that vehicle."

In-kind proponents reference Queensland, Australia’s third-largest state.

When steep deficits and bond-rating downgrades followed the 2009 recession, Queensland, in the face of public opposition, contributed a state-owned 43-mile toll-road network to its pension fund. Queensland received a credit equivalent to $2.3 billion in U.S. currency against its underfunded pension.

The pension fund, in turn, hired professional infrastructure managers who improved operations and expanded the toll road.

While fairly common for corporate pensions, in-kind contributions for public pensions are rare, although Hartford two years ago received a $5 million credit against its pension liability and cut its budget deficit when it transferred the title of Batterson Park to the city’s pension fund. The city owns the park even though it sits in suburban Farmington.

Villanova School of Business professor David Fiorenza said concept is viable in cities and states like Connecticut that have run out of options.

“Real assets, over long periods of time, will appreciate greater than other assets and the legacy obligation trust should be reviewed by all finance officers in municipalities that are experiencing unfunded pension and other liabilities,” said Fiorenza, a former chief financial officer of Radnor Township, Pa.

Valuing publicly owned infrastructure assets is difficult, said Michael Bennon, managing director of the Global Projects Center at Stanford University. “Anecdotal evidence exists that valuations can vary widely,” Bennon wrote in a white paper with Ashby Monk and Young-Joon Cho.

In Chicago, for example, the winning consortium for the Chicago Skyway toll bridge concession paid the city $1.83 billion, more than $1 billion higher than the runner-up bidders. By contrast, Chicago’s sale of a 99-year parking concession triggered a report by the city’s inspector general that it extracted too low a price.

Detroit's bankruptcy settlement featured creditor acceptance of the transfer of valuable real estate along the city's waterfront and downtown areas, including the land housing the vacant Joe Louis Arena and a lease of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel.

Richard Dreyfuss, a Hummelstown, Pa., actuary and an adjunct fellow with the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, worries that creditor costs in Detroit may increase to unsustainable levels just to protect initial investments.

Other uncertainties, he said, include who and what determine the fair value of assets and what happens if the trust eventually needs to liquidate a pension asset to pay annuitants.

Intangibles are also in play, he added.

“How do cities, such as Detroit, overcome their image of high taxes, high crime and marginal schools?”

Dreyfuss called the crowding-out concept a myth, “given the clear majority of public pension systems continue to underfund, or short-change, their systems using rosy asset return assumptions.”

He added: “Given pensions represent a type of deferred wages, do overall public-sector salaries and benefits contribute to ‘crowding-out’ proper pension funding?”

Despite the cry for urgency by Connecticut’s fiscal stability panel, lawmaker reception to some of its sweeping proposals is an open question, given the sharp political and cultural divide in the state. The Senate is deadlocked 18-18 while the Democrats hold a modest 80-71 advantage in the House of Representatives.

Republicans and representatives of the auto and trucking industry generally oppose tolls, while advocates within some of the state’s larger cities, including New Haven and Bridgeport, say the call for a $1 billion annual cut in Connecticut’s operating budget would jeopardize social-service programs for poor people.

Dan Livingston, an attorney for the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition, called the report “dead wrong on labor,” notably the recommendation to remove health and retiree benefits from collective bargaining.

“On a whole, we have to tell you it would take this state backwards,” said Livingston.

Parochial city-suburb divides have been in play over generations.

The report, said Livingston, “deliberately shies away from talking about the antiquated government structure which makes people in Avon believe they can move forward while people in Hartford move backwards, and people in Fairfield move forward while people in Bridgeport move backwards.

“Our state needs to courageously address these things.”