DALLAS – Twelve years after launching the arduous process of creating a municipal power utility, Boulder, Colo., is nearing a turning point in its legal battle with investor-owned Xcel Energy.

Boulder is hoping to succeed where many other local governments have failed.

In hearings scheduled July 26 through Aug. 4, the Colorado Public Utilities Commission will consider the city's plan to separate from Xcel and purchase the electrical infrastructure through a potential bond issue.

Rated triple-A by Moody’s Investors Service, and S&P Global Ratings, Boulder, an affluent college town of about 105,000, had $179 million of outstanding debt according to its most recent financial report. The city’s water and sewer system carries a rating of Aa1 from Moody’s and AAA by S&P.

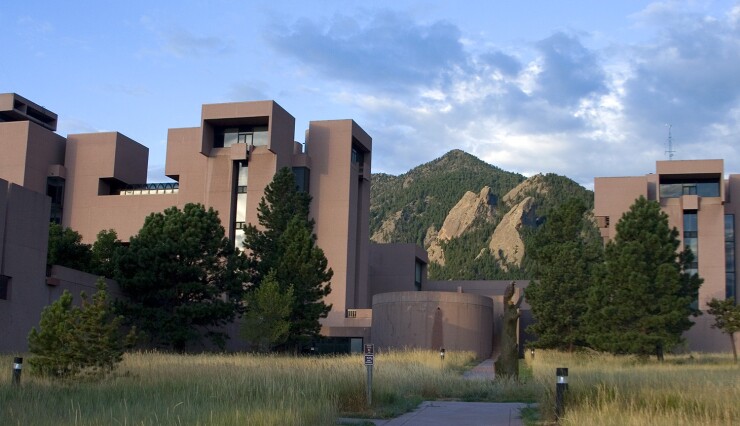

Home to the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the University of Colorado, Boulder has long promoted environmental causes, including a successful bond proposal to buy open space.

In setting the dates for the hearing, PUC chairman Jeff Ackerman compared the proceedings to a divorce while emphasizing that the commission’s role is not that of a “relationship counselor.”

“What we are doing here at the commission is determining the legally appropriate terms and conditions by which the divorce can proceed,” Ackermann said.

At an April hearing, the PUC confirmed that Boulder had the right to create a municipal utility as approved by its citizens. However, Colorado’s constitution provides no guidance on how to municipalize an investor-owned utility.

The PUC, which regulates Xcel, must also determine the limits of its own authority to direct the process. The commission told Boulder to clarify its plan for operating the power system once the local utility is in development. The city originally proposed buying the assets, then leasing them back to Xcel as operator.

Watching the process with an eye toward following Boulder’s path is the southern Colorado city of Pueblo, which is considering ending its contract with Black Hills Energy. In 2005, Pueblo voters strongly rejected a proposal to municipalize the local assets of Aquila, then Pueblo’s energy provider. The company that became Black Hills Energy subsequently acquired Aquila.

If Boulder succeeds in splitting with Xcel, it would lead to Colorado’s first municipal utility conversion in more than 70 years. The state currently has 29 municipal electric systems that serve about 18% of the state’s electric customers.

Minneapolis-based Xcel operates in eight states, with 1.4 million electricity customers in Colorado. It has fought hard to keep Boulder in its portfolio, offering to develop a wind farm and fulfill the city’s environmental goals.

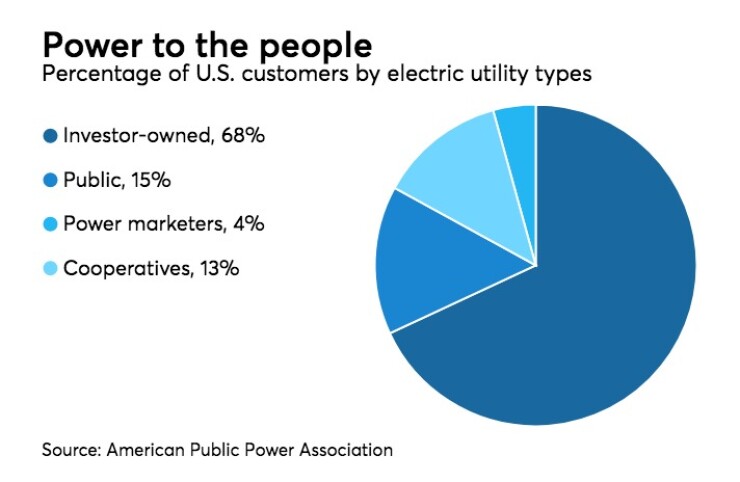

Nationally, only 12 new public power utilities were formed between 2004 and 2014, according to the American Public Power Association.

“It’s a lengthy process,” said Ursula Schryver, vice president of education and customer programs at APPA. “Right now, the driving force is access to renewable energy sources. Sometimes it’s economic development. Existing utilities are usually very unwilling to sell the utilities.”

“There are so very few cities that have done it that there are not that many people to talk to,” said Bob Eichem, Boulder’s chief financial advisor.

Indeed, the obstacles to “municipalization” are daunting, ranging from prolonged court battles and high start-up costs to voter opposition to taking on debt.

On June 13, the Bainbridge Island, Wash., City Council halted plans to convert to a municipal utility after a two-year feasibility study. The council instead called on Puget Sound Energy to improve reliability and reduce carbon emissions.

Where Bainbridge Island failed, Jefferson County, Wash., succeeded in 2013, taking 18,000 customers from Puget Sound. The new utility bought the PSE assets for $103 million.

In 2015, voters in Millersburg, Ore., voted 2-to-1 against borrowing $40 million to buy Pacific Power’s assets for its own municipal utility.

Just beginning the process is Decorah, Iowa, whose city council voted in March to fund a $60,000 to $70,000 feasibility study of municipalizing a portion of Alliant Energy’s assets.

Santa Fe, N.M., has pressured Public Service Co. of New Mexico for years over its operation of a major coal-fired plant with the threat of converting to a municipal utility. Since 2016, the rhetoric has cooled as the effort has stalled.

“Really nothing has moved forward,” said Nick Schiavo, Santa Fe’s public works director. “We actually don’t have a path forward unless the utility wants to sell to us.” Paul Shipley, spokesman for PNM, said the utility has addressed Santa Fe's concerns about coal-generated energy. Current plans for the San Juan Generating Station call for PNM to exit the plant when its coal contract expires in 2022.

"PNM would be coal-free by 2031," he said.

Fitch Ratings analyst Dennis Pidherny said that situation in Santa Fe is more common than successful conversions.

“If you took the body of discussion over the last few decades, there’s a lot more smoke than fire,” Pidherny said. “These deals get consummated at a much lower rate than the discussions. Generally, it arises out of some crisis or disagreement over rates. The fact of the matter is that it invariably comes down to a bid and an ask. The owner of the assets thinks the value of the assets is worth a lot more than the purchaser.”

One of the successes Pidherny noted was that of Winter Park, Fla., which created a municipal power utility in 2005 with nearly $50 million of revenue bonds to buy the assets of Progress Energy Florida, now Duke Energy. Winter Park also serves as model for Boulder.

The Central Florida city has issued new debt for improvements such as undergrounding power lines, which was one of the prime motivators for the utility’s creation. The utility had $68.2 million of electric revenue bonds outstanding as of Sept. 30.

City manager Randy Knight said Winter Park is about halfway to its goal of placing all power lines underground. "At our current rate we will complete the undergrounding in nine more years,” Knight said.

With that project in midstream, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings have negative outlooks on the system’s debt citing little or no reserves. Moody’s rates the system Aa3, while Fitch maintains an equivalent AA-minus rating.

“We have budgeted all of our profits to underground and improve the system so we do have very little unrestricted cash on hand,” Knight said. “We are comfortable with this because as a city, we have a lot of cash on hand in other funds that could be used if there were a need to do so. We also have an $8 million line of credit that we could draw on if we had an extreme emergency.”

Generally, Knight said the city is pleased with owning is own electric system.

“The reliability has been improved substantially,” he said. “Our restoration after storms has been impressive. Our rates are lower than what our customers would be paying under the predecessor utility.”

Los Angeles County, Calif., has also created a new energy utility, but the model is not considered municipalization of investor-owned facilities. Instead, the newly created Los Angeles Community Choice Energy will compete with Southern California Edison by aggregating energy from renewable sources and offering it to 82 eligible cities and unincorporated areas of the county.

Authorized by state legislation in 2002 and 2011, “community choice aggregation” allows local governments, including counties and cities, to purchase electricity in the wholesale power market and sell it to their residents and businesses at competitive rates as an alternative to power from an investor-owned utility.

Similar environmental motives prompted Boulder to begin looking into converting to a public utility in 2005 in anticipation of its 2010 contract renewal with Xcel. The city won voter support for a municipalization tax in 2011 and beat back a 2013 referendum seeking to halt the project.

In approving the plan, voters capped the cost of acquisition at $214 million. If courts find the assets more valuable than that, the city faces a “go or no-go” decision. The city made an initial offer of $120 million and will pursue condemnation through the courts if the PUC issues a favorable ruling.

The parameters for completing the deal also call for rates equal to or lower than Xcel’s at acquisition and sufficient revenue to cover operating costs plus earn a debt service coverage ratio of 1.25x.

In the process, the new utility must increase use of renewable energy and decrease emissions.

Boulder’s PUC petition seeks to acquire all or portions of nine substations and the 115-kilovolt transmission loop serving the city, as well as related facilities, equipment and lines.

"Owning and operating our own utility will not only allow us to be better environmental stewards and energy consumers but will also help us make our local economy even stronger,” said Heather Baily, executive director of energy strategy and electric utility development for the city. “Our utility would create jobs, foster innovation and emerging technology and support the types of businesses that make Boulder unique."

While some cities sought to municipalize, many went the other direction, selling public utilities to private operators. Between 1980 and 2012, some 76 public power utilities were sold, with 45 going to investor-owned utilities and 31 to rural electric cooperatives, according to APPA.

Colorado Springs, which operates the state’s largest combined utility, considered Xcel’s offer to buy its power system in 2013 but decided to turn down the offer after a year-long feasibility study.