Dallas Area Rapid Transit could face a reckoning with financial consequences next year.

Four of its 13 member cities — Plano, Irving, Highland Park, and Farmers Branch — decided last month to ask voters in May if they want to withdraw from the agency, which provides bus, rail and other transit services in a more than 700-square-mile area.

The city council in Addison, which gets rail service on the 26-mile Silver Line

DART is one of Texas' eight

The main reason the cities cited to ditch DART is inequity between members' 1% sales tax contributions, which totaled $851.78 million in fiscal 2024, and transit services they receive.

A 2024

Plano contributed $109.6 million versus $44.6 million in expenses, while Farmers Branch's disparity was $24.3 million versus $20.8 million and Highland Park's was $6.3 million versus $1.9 million. Irving came out ahead with contributions of $102.2 million and expenses of $123.5 million.

For Dallas, which has the largest representation on DART's board, expenses totaled $690.5 million versus $406.8 million in contributions.

If voters agree to withdraw, transit services would cease in the cities, which would still have to contribute sales tax revenue until their financial obligations, including their share of debt payments, are fulfilled, DART's Board Chair Randall Bryant told a special joint meeting last week between DART and the Dallas City Council's Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

The situation is fluid as some cities that opted for an election offered DART "a certain set of solutions that we also are reviewing right now," he said, noting that measures can be pulled from the ballot 45 days before the election date.

"My biggest focus as the chair of the board is to try to stop these elections and work with all of our cities — those that are (contemplating an election), but also those like Dallas that are not contemplating — and ensure that whatever we agreements we come to with those four or five possible cities doesn't hurt or harm the cities that are not taking up those elections against us right now as well," he said.

DART had $3.86 billion of senior lien

A key factor in KBRA's rating is DART's governing legislation, which "ensures full and timely payment of debt service regardless of whether one or more member communities opts to withdraw," said Pete Stettler, a senior director.

"From an operations standpoint, the withdrawal of one or more member communities could introduce certain financial and logistical pressures, including loss of sales tax revenue and the immediate cessation of service within the withdrawn community, with limited exception," he said in a statement. "Longer-term, inefficiencies created by a member withdrawing could lead to service cuts and other, potentially difficult budgetary decisions."

Fitch Ratings, which upgraded its rating on DART's outstanding Series 2007 bonds last year to AA from AA-minus based on revised rating criteria, is closely monitoring the elections, according to analyst Omid Rahmani, who said the loss of recurring operating revenue from the four cities would pressure DART's credit profile.

"Lower pledged revenues would pressure debt service coverage metrics, and could necessitate revisions to capital plans and funding strategies," he said in a statement. "While DART could adjust service levels and reduce expenses, cost cuts would likely be insufficient to fully offset revenue losses of this magnitude, increasing reliance on reserves or external funding."

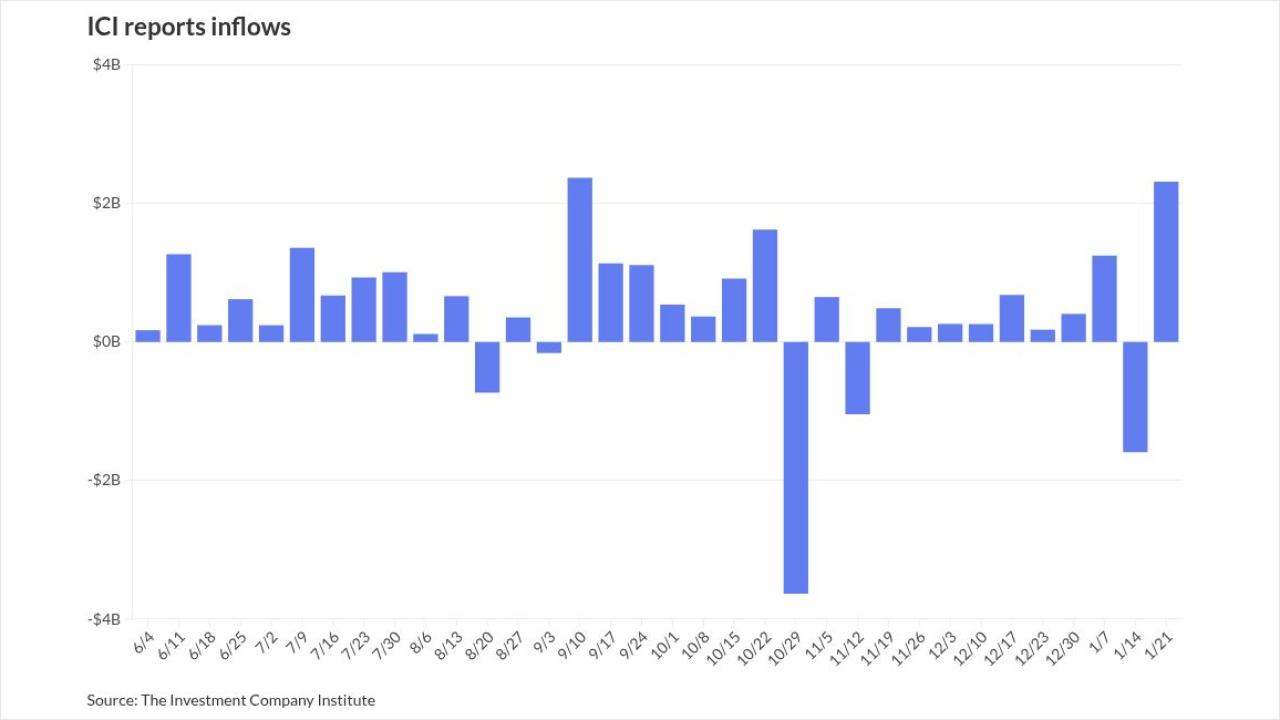

The potential financial hit to DART comes as U.S. mass transit usage has yet to rebound to pre-COVID-19 levels. An October

"We believe full recovery to pre-pandemic ridership is unlikely for many years, if at all, with future growth more closely tied to slowly developing demographic shifts rather than to a widespread return to in-office work," the report said.

It also noted DART had "

DART

In its October affirmation of DART's Aa2 rating, Moody's said "the stable outlook further reflects DART's continued structural balance despite permanently lower ridership given strong growth in sales tax revenue and strong fiscal management."

Disputes like DART's are not unusual for public transit agencies, according to American Public Transportation Association President and CEO Paul P. Skoutelas.

"Regardless of structure or funding source, however, there is almost always some tension over whether service or project benefits are commensurate with that jurisdiction's contributions," he said in a statement.

After contributing more than $2.2 billion since joining DART in 1983, Plano contended its requests for additional services were denied over the years by the agency. If voters decide to withdraw, additional funding has been allocated "to support alternative transit options that ensure continuity of service for residents who rely on public transportation, including people with disabilities, seniors, and those living on fixed incomes," according to a statement from the city.

In Irving, where the city council voted 9-0 on Nov. 6 to hold an election, officials

Festering discontentment with DART

As introduced,

In an attempt to head off the bill, DART's board in March created its own