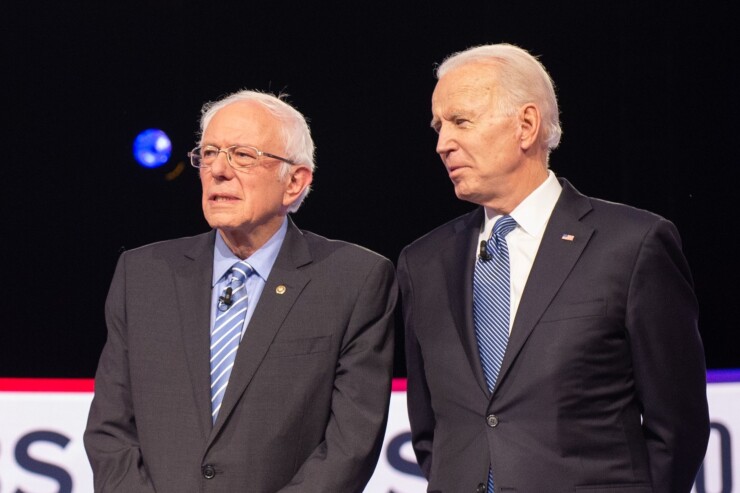

The two remaining candidates with a viable chance of securing the Democratic presidential nomination have grand yet divergent plans for improving America's infrastructure.

Sen. Bernie Sanders’ plan appears to be somewhat fuzzy because it's embedded as part of the Green New Deal that’s a centerpiece of his campaign.

Former Vice President Joe Biden lays out his vision in a separate infrastructure plan that relies partly on policies developed during the Obama administration and on legislative proposals already introduced in Congress.

Both are proposing to spend hundreds of billions of dollars that would need to gain the support of lawmakers in both chambers of Congress.

Following Super Tuesday voting in 14 states, Biden was leading with 616 delegates to the Democratic National Convention to 516 for Sanders with 1,991 needed to win the nomination.

Because of their poor showing on Super Tuesday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg became the latest candidates to drop out of the race.

Biden said at a recent infrastructure forum that it’s “a false choice” to say the next president will have to choose between fixing the nation’s aging infrastructure and moving toward a more climate friendly economy.

“I think you start off by fixing the broken infrastructure in a modern way,” Biden said at the Feb. 16 forum in Las Vegas sponsored by the group United For Infrastructure, citing his plan to install 500,000 charging stations for electric vehicles on existing roads as an example.

Biden was among several Democratic candidates who attended that forum, but Sanders did not.

“I’m glad that so many candidates put out infrastructure plans this campaign cycle,” Zachary Schafer, CEO of United for Infrastructure, said in an interview. “Sanders is one of the candidates that does not have an explicit infrastructure plan.”

Nor does Schafer expect Sanders to issue a stand-alone plan later in the campaign. “Honestly, at this point I think that they have mostly finished putting out their policy proposals,” he said. “He may talk more about infrastructure in the context of other things like climate change, but I’m not aware of any effort by his campaign to announce new policy platforms.”

The issues page on the Sanders campaign website also doesn’t list infrastructure as a major plan, but infrastructure-related issues do occupy a significant part of his outline for a Green New Deal.

Adie Tomer, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program of the Brookings Institution, said Sanders has “absolutely embedded” his infrastructure proposals, making them almost hidden to the casual reader.

“They have used vastly different words for their plans,” Tomer said. “In Sanders case, he is using a broad definition that is absolutely inclusive of a wide swathe of infrastructure categories many of which match up one to one in terms of concepts at the highest levels with Vice President Biden.”

Sanders does propose many specific proposals, including $75 billion for the National Highway Trust Fund, another $2 billion for other surface transportation needs and $5 billion for TIGER grant projects that build or repair critical pieces of freight and passenger transportation networks located in rural areas.

The Vermont senator also would invest $636.1 billion in our roads, bridges, and water infrastructure to ensure it is resilient to climate impacts, and another $300 billion for resiliency.

Another $300 billion would be used to increase public transit ridership by 65% by 2030.

“We will ensure that reliable, affordable public transit is accessible for seniors, people with disabilities, and rural communities,” his campaign website said, adding that Sanders would “promote transit-oriented development to link this service to popular destinations and vital community services.”

Sanders also is a supporter of a water act that would provide $34.85 billion for the Clean Water State Revolving Fund program, the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund program, a new grant program to address lead in school drinking water and other priorities.

Like Biden, Sanders wants to establish a national network of charging stations for electric vehicles. Sanders would spend $85.6 billion for that network “similar to the gas stations and rest stops we have today.”

Most of Sanders other infrastructure related proposals would provide assistance to individuals, such as his $2.09 billion plan to provide grants to low and moderate income households and small businesses to purchase electric vehicles.

Biden proposed restoring the full electric-vehicle tax credit and spending $5 billion over five years in the U.S. Department of Energy to spur breakthroughs in battery and energy storage technology to “boost the range and slash the price of electric cars.”

Biden estimates the cost of installing the 500,000 new electric vehicle charging stations at an additional $1 billion per year for “new grants to ensure that those charging stations are installed by certified technicians, promoting high-paying jobs and benefits.”

Biden also would ask Congress to “immediately spend $50 billion over the first year of his administration to kickstart the process of repairing our existing roads, highways, and bridges.”

He also wants $100 billion to modernize our nation’s schools and $40 billion for a 10-year Transformational Projects Fund, “to provide significant discretionary grants for projects too large and complex to be funded through existing infrastructure programs.”

Biden supports Rep. Jim Clyburn’s proposal for all federal programs to use a formula allocating 10% of funding to counties where 20% or more of the population has been living below the poverty line for the last 30 years.

And in a revival of a proposal developed during the Obama administration, Biden supports a $6 billion, three-year initiative to invest in communities that experienced mass layoffs or the closure of a major government institution.

Tomer does not expect infrastructure to be a key issue in the presidential general election after the two parties hold their nominating conventions this summer.

“Infrastructure is typically not a major campaign issue, especially in the case of the presidential level,” said Tomer. “It is important to know where they are headed, in case they win. You don’t campaign on infrastructure, but you have to govern on infrastructure.”