This article is part of The Bond Buyer’s multi-platform, four-part series on the

We explore how cities of all sizes are being impacted by

For each, we dig in on the problems and discuss potential solutions with a written story and a companion podcast. Additionally, the series features a video discussion spanning all four topics. To see all of our Future of Cities content, please click

After decades of continued population growth for cities in the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused at least a short-term re-contemplation of unending urbanization, threatening the financial futures of cities across the nation.

The urban flight seen since March, and its resultant loss of tax revenue, is weighing on the budgets of cities large and small, but those impacts are being felt differently in large, dense metropolitan areas than they are in smaller, more sparsely populated ones. The most populous cities are feeling the brunt of the blow, but smaller and mid-size cities may be better positioned to withstand the impact and, perhaps, even benefit from the flight from larger ones.

While risk and uncertainty abound, the real risks — and the potential for permanent change — concentrate in the nation’s largest cities. And while those cities number in the few, they have an outsized influence on the nation’s economy and finances.

The large cities

For America’s biggest cities, the urban flight has been pronounced.

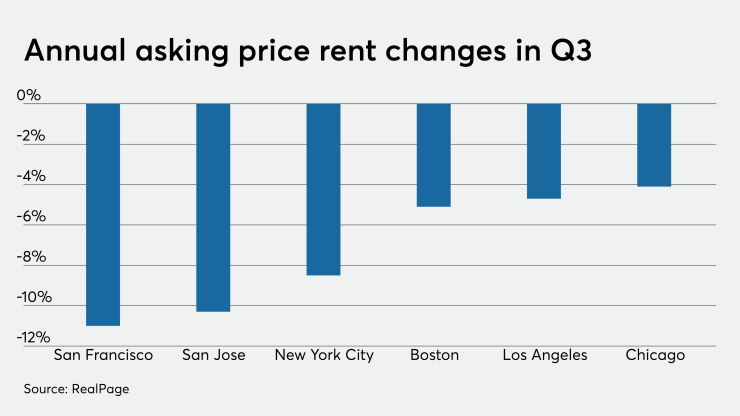

In New York, effective asking rents are down 8.5% year over year, according to

For New York, the epicenter of the pandemic this spring, that population loss comes amid “substantial financial challenges,” as Moody’s Investors Service noted in its Oct. 1 report

“The public health response to the pandemic brought the city’s infection rate down to among the lowest of big cities,” the Moody’s report noted. “The lasting economic consequences, however, will likely be among the most severe in the nation and require significant fiscal adjustments.”

The negative outlook Moody’s placed on the city “reflects ongoing uncertainty about how long the pandemic’s economic consequences will impact the city’s economy and budget, including the return of office workers, business and leisure travel and real estate markets,” according to the report.

The rating action taken against the city notes the agency’s view that “the city cannot shift to a ‘back to normal’ economy until a vaccine is widely available,” highlighting the challenges facing recovery.

Mayor Bill de Blasio's budget team has projected a $9 billion revenue gap through the next fiscal year. The mayor is asking for $12 billion from the federal government, which is stalled over the next rescue package, and is seeking permission from New York State to borrow to cover operating deficits. He’s also said he may have to furlough 22,000 city employees if the federal government doesn’t come through.

If renters and buyers don’t return to New York City, the permanent hole in tax revenue would be incredibly difficult to fill. But Mayor de Blasio says that even if people decide that they would prefer to live elsewhere, “many, many people will sense opportunity.”

“Maybe the opportunity for them is that they can buy a home or buy a condo or a co-op a little cheaper,” de Blasio told The Bond Buyer. “Maybe the opportunity is they can invest in creating a business a little more easily. But what you’re going to see is some people will stand back, other people will surge forward.”

This pattern has repeated throughout the city’s recent history, he said.

“We saw it after every crisis we’ve had. The strength of New York City and the appeal of New York City comes to the fore and people start investing and people start coming here,” de Blasio said. “And that reality of younger folks, particularly folks who are creative and entrepreneurial, wanting to be where the action is, that has not been changed. It may be paused a little while, but it hasn't been changed. So, give us time and we will prove the doubters wrong once again.”

Henry Cisneros, former secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development under the Clinton administration, said that even if the population loss is not ultimately regained, “that’s not all bad for Manhattan.”

“Prices of residences have been going through the ceiling,” said Cisneros, who is vice chairman of Siebert Williams Shank & Co. and has also launched American Triple I Partners LLC, a New York-based firm that manages private equity investments in infrastructure. “If there’s some slight diminution of demand that’s not a bad thing for a more orderly functioning of housing markets. People were having to make life decisions based on rapidly rising escalation of real estate and other costs within the city.”

That may happen slower in certain cities, faster in others. Cisneros said the pandemic may push people to make decisions about staying in or leaving city homes sooner than perhaps the circumstances of their lives would have dictated.

“There are people who are saying, ‘This tests my comfort level,’ and for a variety of reasons will either seek jobs in another place or move to residences outside the core city,” said Cisneros, noting that some of these people “may have been thinking that way anyway because young people reach household formation years and have children and look to a more suburban area — new schools, a larger house, better household prices.”

For San Francisco, the flight has been just as apparent. Effective asking rents in San Francisco dropped 11% in the third quarter, according to RealPage data, while its occupied apartment count declined by 3,637 in that period.

Curtis Erikson, head of capital markets at Preston Hollow Capital, lives about 10 miles north of San Francisco. He’s noticed a large number of people leaving the city, and “For Sale” signs popping up across the region.

“It’s undeniable that COVID has affected the region and people are leaving,” he said. “Add in the extremely high cost of living and it’s a recipe for departures.”

George Friedlander, a 40-year veteran municipal bond analyst, echoed the sentiment.

“Why pay these incredibly high rents to live in a place that you can’t enjoy?” he asked.

In the long run, however, Ian Parker, a managing director at RBC Capital Markets who lives about 20 miles south of San Francisco, believes the city will “always be a desirable place to live and work.”

“The tech industry is here. Young people still flock here,” he said.

Parker said his son, who just graduated from college, plans to move to the city with a few of his friends and share the high rent.

“There are always going to be trends of people coming and going; it’s a transient city and region,” he said. “Sure, you have some folks moving to Portland and Texas, but what those cities and states lack is a social safety net that California has. I’m bullish on San Francisco.”

In Chicago, the pandemic has exacerbated existing out-migration due to issues including high taxes and pension problems in the city and state. Effective asking rents are down 4.1% in the third quarter, per RealPage data.

“It's really a tragedy,” said Michael Belsky. The former mayor of Highland Park, Illinois, a north Chicago suburb, recently joined Hilltop Securities as a managing director and municipal credit analyst.

“We were, as a society, making the urban experience have a comeback,” Belsky said. “You have to remember that part of the urban experience is to exchange ideas and thoughts. It's cultural. And this is affecting all sizes of cities across the country.”

The smaller markets

For smaller and mid-size cities, however, the negative fiscal impact of the pandemic has been less severe. In fact, some say the pandemic could have created an unexpected opportunity for smaller markets — urban, suburban and rural — to capture some of the exodus from the large cities.

“The migration that we all talk about from the big cities to the suburbs, this could actually help rural America,” said Sylvia Yeh, co-head of Municipal Fixed Income at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, noting their tax bases may grow as a result. “We’re going to recover, the U.S. is going to evolve. It essentially could be a ‘buy’ opportunity for investors in smaller issuers. This could actually be a ‘buy’ opportunity to help boost rural America.”

According to Zillow’s

Seattle, near where the first United States cases of COVID-19 were reported, hasn’t seen so much of an exodus of people as a “work from cabin” effect, said the city’s mobility solutions manager Alex Pazuchanics.

“Generally, I’m not seeing people leaving, at least not permanently. Those who are leaving are likely facing forces that were naturally happening anyway — people looking for more space, younger people starting families,” he said. “Seattle has a reasonably high number of single family homes, detached houses, and townhomes. It doesn’t seem like people are fleeing to the hills of Montana. They’re likely working from one of the islands or the mountains for a week or two at a time.”

Density of cities does play a role, as Pazuchanics noted. Being stacked on top of one another in elevator buildings in New York or Chicago is a lot different than a more sprawling, open region, such as Washington, D.C. and its suburbs, or even Houston.

Detroit, which went through bankruptcy in 2013 after decades of decline, had recently started to rebound. A city that offered incredibly cheap real estate was drawing in a younger crowd eager to rebuild the Motor City. This younger generation began peeling back the paint, planting urban gardens, and opening world-class restaurants before COVID-19 struck.

“When COVID-19 hit Detroit, the city moved decisively with testing and social distancing. Detroit’s COVID-19 interventions sped up the reopening of businesses and encouraged continued growth and investment within the city,” said Suzanne Shank, president and chief executive and equity owner of Siebert Williams Shank. “In terms of fiscal preparedness, the city had already been planning for a potential downturn and had doubled its rainy-day fund.”

She said that economic activity within and around Detroit is still robust despite the pandemic.

“Through corporate partnerships created in 2020, the city has seen hundreds of millions of dollars in public and philanthropic placemaking investment in 10 Detroit neighborhoods. Wayne County also has provided over $64 million in grants to support small businesses,” Shank said. “Because Detroit ranks No. 5 in the National Affordability Index according to U.S. News World Report, the city will likely become more attractive to younger professionals looking to settle down as working from home allows more individuals to live wherever they choose.

“There is a very strong likelihood that the revitalization of Detroit will continue well into a post-COVID environment,” Shank said.

Villanova University School of Business professor David Fiorenza said the city has seen a resurgence in urban renewal in the past half decade through the Strategic Neighborhood Fund that “has public, private and philanthropic partners to help rebuild and preserve commercial and residential real estate.”

“The community is attractive as there are park improvements, safe well-lit areas, safer pedestrian crossings, and bike share lanes,” Fiorenza said. “This all adds to the value of what younger people are looking for in a city.”

And Detroit is, in fact, seeing more demand in the rental market. The city saw a 2.4% rise in third quarter effective asking rents, according to RealPage, ranking it among the 10 largest gainers in that time frame.

The future

Despite the near-term challenges brought on by shifting population density, many experts believe the trend will be temporary.

“I've got to believe that things will return to normal,” Hilltop’s Belsky said. “Once there is a vaccine and people feel a semblance of normalcy and safety, our cities will return.”

However, for cities suffering from population loss and massive budget holes, there must be more than belief that normalcy will return. The uncertainty from COVID has put city leaders all over the U.S. in a hard position to plan their out-year budgets, pay for social services, plan their pension funds amid a volatile stock market, and run general functions, such as police and fire and healthcare, while civil unrest also permeates the landscape. From mom-and-pop businesses to big box retailers to governments themselves, the pain is widespread.

There must be a plan to persevere and rebuild. And while stopgap solutions like cutting services and spending and raising taxes could buy time, cities need to think long-term.

Cisneros said the challenge for government officials now is how to make public systems better and safer in a post-pandemic world — with perhaps less revenue or federal help.

Despite those realities, one idea for cities to reshape entire economies is investment in sustainable infrastructure.

“The pandemic has laid bare a world in crisis. Environmental degradation and climate change continue to threaten lives and livelihoods around the world. Economic inequality within and between societies is becoming untenable,” according to the World Economic Forum. The Forum said to address those deficiencies, economies and societies “must be supported by high-quality, future-focused infrastructure.”

The “Great Reset,” as some are calling it, will be shaped by sustainable infrastructure.

There is a “tide of opinion swelling toward the idea that the world we build after this pandemic needs to be significantly different to the one we had before,” the World Economic Forum said. “The dual economic and health shocks of 2020 seem to have increased the

Though radical thinking and sustainable investing during the pandemic will likely be difficult for city leaders, the outcome of the upcoming elections could perhaps open the door for a broad infrastructure bill down the road.

Chip Barnett contributed to this story.