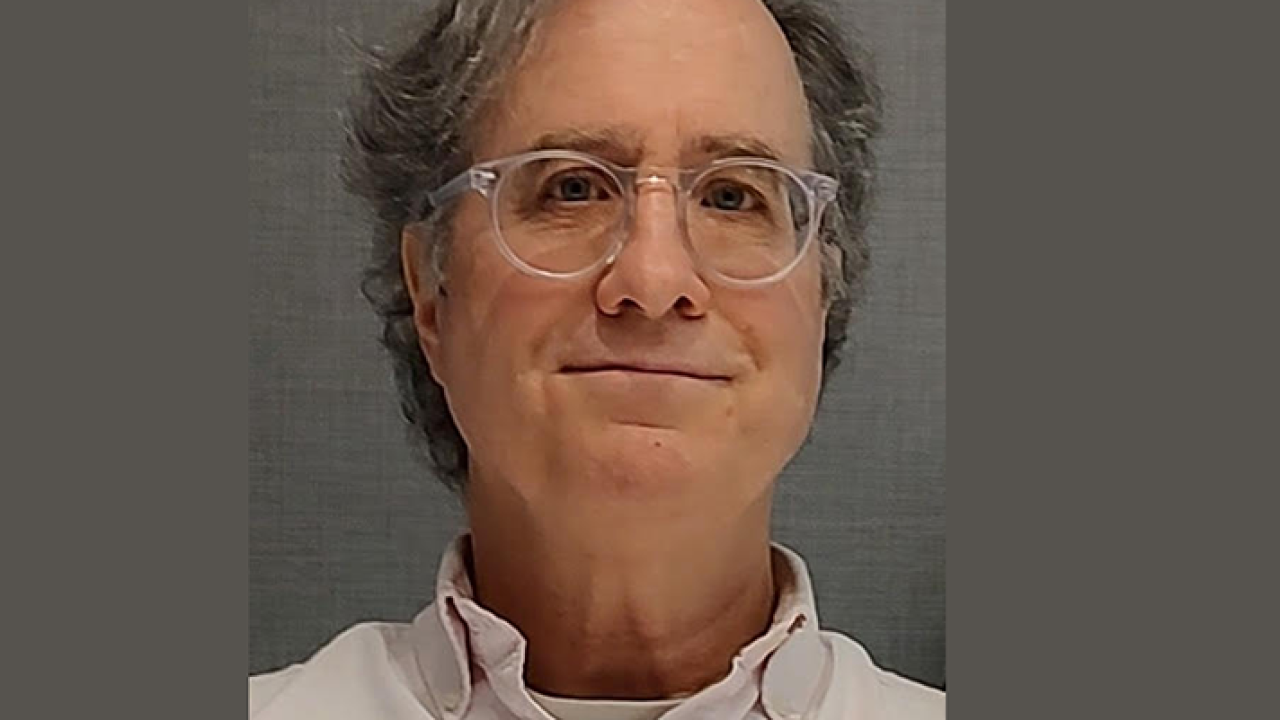

LOS ANGELES — For Fresno Mayor Ashley Swearengin, rating upgrades that moved much of the city's debt out of junk bond territory show that steps taken to get the city on sound fiscal ground have worked.

"I remember in August 2013 sitting down in one of my staff member's office," she said. "She had a copy of Time magazine."

The staff member pulled out an article on which city would be the next to go bankrupt – and Fresno was listed as one of several cities.

The city wasn't going bankrupt even at that troubled time, and in fact was already on an upward trajectory, the mayor said.

Still, she said, "that was a scary moment, as mayor, to see that view of the city from outside of the city."

With a half-million residents, Fresno, in the heart of the agricultural Central Valley, is California's fifth-largest city.

Last week, Moody's Investors Service returned much of the city's lease revenue, pension and judgment obligation bond debt to investment grade.

"The upgrades reflect meaningful improvement in the city's fundamental economic profile, with continued growth in taxable property values, sales tax collections and employment," Moody's analysts Helen Cregger and Eric Hoffman wrote.

Upgrades included a two-notch bump to Baa2 from Ba1 for lease-backed obligations and an upgrade to Baa3 from Ba2 on the city's 2006A Convention Center bonds.

Moody's maintained a positive outlook on each of the bond credits and affirmed the city's A3 issuer rating with a stable outlook.

Fresno's 2002 pension obligation bonds and 2002 judgment obligation bonds remain in junk territory with upgrades to Ba1 from Ba2.

In all, Moody's upgraded $306 million of debt.

Swearengin said that when she was elected in 2008, Fresno appeared to be weathering the Great Recession better than most cities, because it had reserves.

The city's industrial businesses were hit hard by the recession, but the assessed value of properties in the city had not fallen as hard as some other California cities.

But in the first quarter 2009, the city's finance director knocked on the door to tell her that it looked like the city had a budget shortfall of $4 million.

She and city leaders reacted by creating a list of tiered budget cuts and took action on a quarter-by-quarter basis.

"We did ten or eleven rounds of budget cuts," Swearengin said. "Every quarter, we were comparing the revenues to the budget. We had labor contracts locked down in the boom days that were coming home to roost and we did not have the money."

The $17 million in general fund reserves was not enough to cover the deficits. It was half of what they needed.

"Our reserve was too small and we did not have anything to fall back on, so we just started cutting," she said.

There were other cities in central California that thought they would just ride out the recession and continued business as usual, she said.

"Thankfully, we cut early," she said, "because the recession lasted longer, and was deeper, than anyone expected."

City leaders established tiers of cuts that included layers they hoped to never reach.

She called the list of tiers the "table of terror."

"The steady every quarter cuts enabled us to get through; we just didn't have any cash," she said.

The city discovered in 2011 that it had fallen into a negative fund balance, because so much had been charged against the reserve. The city had $17 million in reserves, but $36 million in negative fund balances.

One positive for the city, however, was that it doesn't have unfunded pension liability. It has one of the best-funded pensions in the nation, Swearengin said.

"The city's fully funded pension system is a credit positive, although these liabilities could increase future risk depending upon investment returns and negotiated benefits," Moody's analysts wrote.

Though the city's actuarially required contribution has declined as a percentage of the general fund budget since fiscal 2015, Moody's analysts said the lack of a negotiated settlement with the fire union exposes the city to downside risk for future funding requirements.

Fresno also had net unfunded other post-employment benefit obligations totaling $72 million, or 59% of covered payroll, in fiscal 2015, according to Moody's.

Analysts also cited as challenges the city's still weak, but recovering economy that has unemployment levels at 9.5% that substantially exceed state and national figures; a high poverty level; the city's still narrow reserve levels; limited liquidity and constrained budgetary flexibility.

Fresno began building the reserves back up two years ago and now has a $20 million general fund reserve, Swearengin said. The city needs to get to $30 million for its target of having a 10% general fund reserve.

The city had a practice – as many cities do – of funding unfilled positions, rather than cutting. One of the things Fresno did during the years of financial turmoil, Swearengin said, is to right-size that.

"We had 4,100 employees and now we have 3,300," she said. "Of those jobs, only 200 to 300 were layoffs. The rest were people who left, retired, or positions that had been held vacant, but were funded."

Sound management practices have guided the city through the adoption of updated zoning laws and economic development objectives, a revised reserve policy and favorable union agreements, Moody's wrote.

The mayor is confident that the two bond issues still rated junk will move in to investment grade when the city's audited financial documents for fiscal 2017 are released later this year.

But the bonds still rated junk have some unique features.

The city of Fresno has a "pension override tax." The proceeds of this limited tax are less than the amount needed to pay debt service on the city's pension obligation bond debt service, according to Moody's.