For the municipal bond industry, 2015 marks the midpoint in what may turn out to be the decade of the bankruptcy.

Four of the five largest municipal bankruptcy filings in United States history have been made in roughly the last three years, a trend analysts attribute to the aftereffects of the 2008 credit crisis and Great Recession, as well as changing attitudes about debt.

"The crash of 2008 and five years of stagnation preceded by years of escalating wages, pensions and Other Post-Employment Benefits set the stage for our recent Chapter 9 filings," said Arent Fox partner David Dubrow.

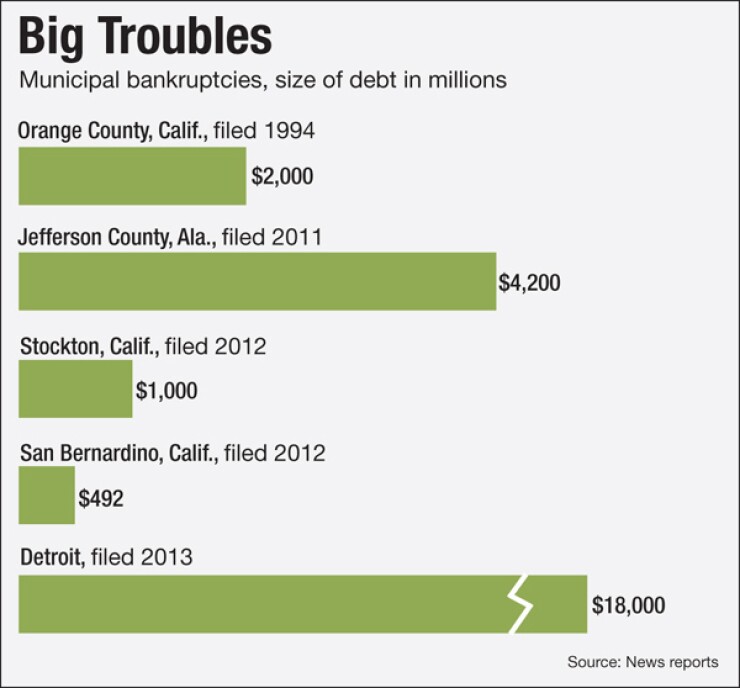

Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy was adopted in 1937 but had been rarely used, particularly by large governments. However, since November 2011 San Bernardino, Calif., Stockton, Calif., Jefferson County, Ala., and Detroit have filed four of the five largest bankruptcies as measured by total obligations. Orange County, Calif.'s 1994 filing ranks third, behind Detroit and Jefferson County.

Municipal Market Analytics' Default Trends said 2014 had the largest par value for defaults of any year since the publication's founding in 2009.

To explain the elevated rate of municipal defaults, eight municipal experts interviewed by The Bond Buyer and four professionals at Kroll Bond Ratings, who wrote a report on muni defaults in the fall of 2013, frequently mentioned two factors.

Everyone agreed the depth of the Great Recession was a main cause of the latest round of big bankruptcies. When the broader economy started to pick up, recovery never came to these municipalities, leaving revenues depressed.

For example, in Detroit a weak local economy combined with abandoned properties and a dwindling population to shrink revenue, even as the nation's economy resumed growth.

The city's General Fund revenues slid from $1.487 billion in fiscal year 2007 to $1.268 billion in fiscal year 2009 to $1.22 billion in fiscal year 2011 to $1.043 billion in fiscal year 2013, the last year that a comprehensive annual financial report is available.

Though none of the big bankruptcies took place while the U.S. economy was shrinking, the recession triggered other events that contributed to the need to file for protection.

For example, much of Jefferson County's debt was in $3.1 billion of insured variable- and auction-rate bonds sold for its sewer system before the recession. When the downturn hit, Lehman Brothers collapsed, market-rate debt yields skyrocketed in early 2008 and the ratings agencies downgraded the bond insurers. The county had billions in variable rate debt on which it now had to make much higher payments. The debt burden and general fund cash-flow problems ultimately led to its bankruptcy, which was the biggest ever at the time, based on its $4.2 billion of debt.

Merritt Research Services president Richard Ciccarone said that the recession and credit crisis put governments that were overexposed to debt and liabilities on one of two roads to bankruptcy.

In one, municipalities that were dependent on continued rapid growth, found themselves saddled with obligations they could no longer meet.

For example, Ciccarone cited "places in California that had committed to optimistic budget forecasts with expensive operating and debt structures, typified by generous labor contracts, which are usually the basis of attendant pension levels."

Connie Cochran, public information officer for Stockton, said the city's assumption in the last decade that it would continue to experience rapid growth was a factor in its 2012 bankruptcy.

In the other road, some municipalities that had already been in long-term structural decline before the recession, found themselves with little backing.

"The states couldn't or wouldn't help out during the credit crisis given the demands and threats to their own credit standing," Ciccarone said.

David Litvack, U.S. Trust head of tax-exempt research, noted that plunging housing prices in the recession were especially problematic for municipal governments, which are heavily dependent on property taxes.

The Great Depression led to at least as dramatic defaults as those found in the last few years. James Patterson in his book The New Deal and the States, wrote that South Carolina, Arkansas, and Louisiana "were beginning to default on their debt" in 1932. Chapman Strategic Advisors managing director James Spiotto said only Arkansas defaulted on its debt and it did so in 1933.

Default rates were far higher in the heart of the Depression, reaching about 18% of municipal par outstanding in 1933, according to Income Securities Advisors. By comparison the rate was 0.11% in 2012, also according to Income Securities Advisors.

These defaults include draws on reserves for payments, bankruptcies, nonpayment covered by insurers, as well as simple non-payments.

In addition to the economic downturn, a factor cited by majority of the analysts was growth in pensions and other post-employment benefit obligations.

"The single biggest issue facing us was the $540 million unfunded liability for retiree health insurance, which has been eliminated through the bankruptcy process," Stockton's spokeswoman Cochran said.

Some analysts said that in recent decades some municipalities had granted overly-generous retirement benefits that were not adequately funded.

Demographic factors, like the retirement of the Baby Boom, led pension obligations to become more important, said NewOak managing director Triet Nguyen.

To some degree the recession exacerbated the underfunding of pensions. The recession triggered a plunge in the stock market and other financial markets, greatly expanding unfunded pension liabilities, Kroll managing director Kate Hackett and three other authors wrote in a report titled "Municipal Defaults in a Post-Bankruptcy World."

While most of the analysts mentioned the Great Recession and retiree pensions and benefits as causes for the recent bankruptcy wave, analysts were less united about other causes.

National Public Finance Guarantee Managing Director Tom Weyl said that in addition to "overly generous" pensions and OPEBs, some municipalities provided above-market salaries for government workers. Government salaries and benefits that were higher than those for the cities' other citizens, contributing to Detroit's and Stockton's bankruptcies, said Weyl, who made the comments while he was director of municipal research at Barclays.

Several analysts said governments' changing attitudes contributed to the recent bankruptcy wave. Kroll, Litvack, and Spiotto said some governments' commitment to paying debt wavered, with Spiotto picking out Jefferson County as an example.

Kroll "believes that this change in attitude towards repayment of debt represents the greatest risk to the stability of the municipal credit markets," the report authors wrote.

Ciccarone and Dubrow said state governments in recent years have sometimes shown less inclination to aid struggling municipalities than in the past.

The federal and sometimes state governments have been increasingly resistant to help government bodies underneath them through the use of more debt, like New York State's enhanced Municipal Assistance Corp. financing for New York City in its crisis in the 1970s, Ciccarone said.

"In Detroit the liabilities were enormous relative to Michigan's own debt," Ciccarone said. "If Michigan were to adopt the debt, it would have threatened the state's own fiscal stability and credit standing in the market. It may have also created pressure to assume debt of other distressed local governments in the state.

"The reluctance to take on debt (including the Tea Party influence) factored in Jefferson County's relationship with Alabama," Ciccarone said, referring to the political movement to reduce taxes and spending. "The state of Alabama also appeared to want to distance itself from the unique aspects of Jefferson County debt crisis associated with bad management, corruption and charges of imprudent out-of-state debt influences."

Several analysts said the infiltration of corporate bankruptcy experts into the municipal bankruptcy space contributed to Detroit's decision to file for bankruptcy and may influence cities to file in the future.

Detroit could have achieved similar cash flow savings through a more traditional municipal restructure, Municipal Market Analytics managing director Matt Fabian said. But the state only consulted taxable restructuring advisors. So the governor hired Kevyn Orr, whose background was in corporate bankruptcy, as emergency manager for Detroit, putting the city on a path to use the Chapter 9 process.

Since analyst Meredith Whitney in 2010 made her prognostications of widespread bankruptcies, there has been a migration of corporate bankruptcy advisors into the municipal space, Fabian said.

"Lately the legal interpretation of a general obligation bond has softened," Nguyen said. "It's corporate bankruptcy leaking into municipal bankruptcy."

An alternate factor in the rise in big municipal bankruptcies was that credit swaps and derivatives hit many municipalities hard during the Great Recession. Whereas in earlier recessions such hedging contracts had helped, the credit crisis turned them into problems for some municipalities, Fabian said.

Weyl pointed to another recent development that has led municipalities to experience unwanted volatility in their finances. Many governments have introduced to so-called "millionaire's taxes" in recent years. However, tax revenues from these drop off sharply in recessions and this may have contributed to some bankruptcies.

As for the future, most analysts said there would be no major bankruptcies, or only a few, in the coming two or three years.

"The loss of [the ability to borrow] or a prohibitively expensive market access to borrow for capital projects is still the biggest deterrent to default and/or bankruptcy," H.J. Sims senior credit analyst Richard Larkin said. "In addition, the 'Big Bogeyman' of underfunded pensions has faded into the background as strong stock market performance has dramatically improved the asset positions of public pension funds."

Nguyen, Fabian, and Litvack all said they were concerned that some Puerto Rico public sector issuers may default with or without the use of a bankruptcy process.

The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority is currently reorganizing its business and may be headed for what would be the largest bond default in U.S. history. If PREPA does default, it remains to be seen whether the debt restructuring would be done on a negotiated basis outside of bankruptcy or if PREPA will use Puerto Rico's new bankruptcy process for public corporations.

Fabian said Puerto Rico is unique, and even if it does restructure its debt, it would not affect the municipal market generally.

Municipal bankruptcy remains the worst option for most cities, Fabian said. Detroit's bankruptcy did not resolve the city's problem with declining revenue. Unless it gets its revenues to grow, he said, "It's just a matter of time before it gets back into a distressed situation."