SAN FRANCISCO — The California Supreme Court last week rang the death knell for the state’s redevelopment agencies, sparking questions about how their existing obligations will be met.

The high court upheld legislation that abolishes redevelopment agencies, while striking down a companion law that would have let the RDAs survive if they gave up revenue to the state.

The decision, feared by many but not wholly unexpected, starts the process of unwinding California’s 400 redevelopment agencies and transferring obligations like bond debt to new entities.

“I think folks are wrestling with the reality that redevelopment agencies are really gone,” said Stephen Ryan, a lawyer with Cox Castle & Nicholson in San Francisco with a focus on California redevelopment law. “The real question is what really is an obligation and what is not.”

The new law sets up a complex review process to determine what are “enforceable obligations” that must be honored after the ax falls on the RDAs.

Ryan said that any obligations —such as projects, land deals or intergovernmental loans — approved in 2011 by RDAs will likely be up in the air until the approval process outlined in the bill fleshes them out. He said bonds that have already been sold should be safe.

The law upheld by the court, which passed on June 29, 2011, stated that RDAs would be eliminated on Oct. 1, 2011; that date has now been delayed until Feb. 1 by the court. The law also says that the validity of bonds or other obligations issued or entered into after Jan. 1, 2011, could be reviewed for up to two years after the action.

The Supreme Court’s decision leaves cities and counties, which run the redevelopment agencies, scrambling to understand what’s next and whether the obligations incurred by RDAs over the last year will hold up.

Since the law passed, the agencies have been banned from “issuing or expanded debt of any type, expect for emergency refunding bonds, under certain conditions.” It also prevents them from making loans, entering into new contracts or amending them, as well as selling assets or buying land.

With the uncertainty surrounding obligations just one piece of the various challenges facing local governments, a push has already begun to craft new legislation to clarify or modify the terms of the RDAs’ dissolution, and possibly create a new form of redevelopment.

Jim Kennedy, interim executive director of the California Redevelopment Association, said it is helping draft a bill to extend the deadline to dissolve the agencies until April 15, which would give lawmakers time to consider how to handle the dissolutions and possibly reinvent redevelopment.

If the attempt to reinvent RDAs fails, he said, the association would likely turn to creating a bill that would help clean up the elimination legislation.

The Legislature passed a cleanup bill related to the RDA legislation last year that was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown, who said he wanted to wait until the Supreme Court decision before changing the law.

The state’s approximately 400 RDAs have $20 billion of tax-allocation bonds outstanding.

“Right now, it is a mad scramble to comply with [the law] on the part of hundreds of cities that have to deal with a lot of unanswered questions in a short time frame,” said Larry Kosmont, a local government consultant, member of the California Redevelopment Association board, and also interim city administrator for the fiscally troubled California city of Montebello.

Many cities have been closely entwined with their redevelopment agencies, moving various obligations — including loans and asset transfers — out of each others’ budgets.

The validity of transfers done since the beginning of the year are of particular concern to local governments, according to Kosmont.

He said the Feb. 1 deadline for the elimination of the redevelopment agencies is just too close for cities to handle all of the changes, which include layoffs.

“It is like a busted-up football play — someone has to call a time-out,” Kosmont said. “It is just a mess.”

He said lawmakers need to produce some sort of legislative fix fast to give guidance to the cities and counties, and also to give them some type of avenue for redevelopment going forward.

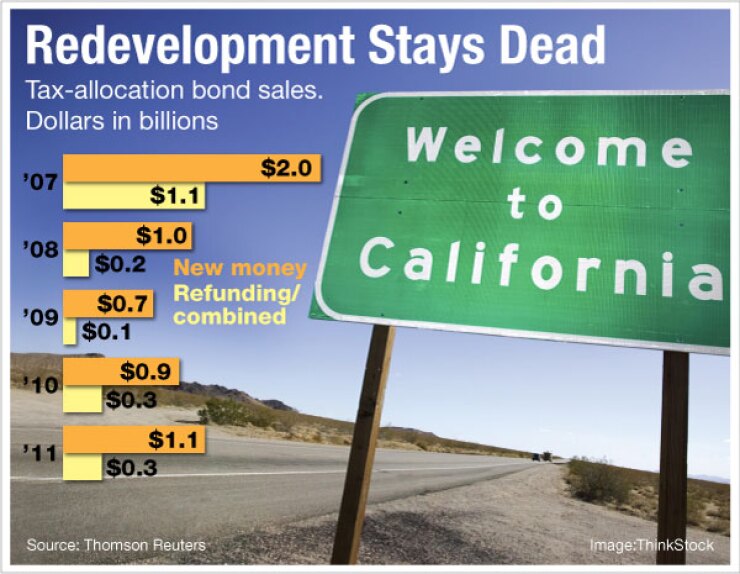

Brown’s January 2011 announcement of his proposal to eliminate RDAs sparked an avalanche of tax-allocation bond issuance from the agencies.

By the end of June when the legislation passed, California redevelopment agencies had already sold $1.1 billion of new-money tax-allocation bonds, the highest such total in four years despite a generally down year in the primary municipal market.

Those bonds that have been sold appear safe from harm, according to the state and experts.

The agencies collected the incremental property-tax growth in areas they designated “blighted” and used it to back bonds sold to fund economic development and affordable housing.

The California Department of Finance has estimated that $2.2 billion in debt service for bonds and other payments will need to be set aside out of the $5 billion in annual RDA tax-increment revenue.

In theory, that leaves $2.8 billion that will be divided up among local governments, particularly school districts. Money sent to schools will ease pressure on the state budget, which will have to send those districts less money to reach per-pupil spending formulas.

“We think it is very plausible that a scenario could play out where the disputes are so pervasive that the state ends up realizing very little revenue in the near term,” Kennedy said.

Under the terms of the law upheld last week by the Supreme Court, redevelopment money to pay debts will be put in a special fund and bondholders will get paid. But some debts may fall under scrutiny.

All of the RDA obligations must pass muster at several levels. Each agency will be under the jurisdiction of a new oversight board, while obligations must also be signed off on by the county auditor-controller and finally by the state Finance Department.

The law reverts all of the assets and liabilities of the redevelopment agencies to a “successor agency,” likely the local city or county, that will be required to wind down the RDA.

The successor agency will put together a payment schedule for the RDA liabilities that will be then passed on to the county auditor-controller, state controller and then the Finance Department.

The legislation also requires the local auditor-controller to perform an audit of the redevelopment agencies to determine the amount of tax-increment revenue that each RDA had been collecting. That money would then be put into a trust fund in the county that would be used to pay debts and give leftover funds to other taxing entities — such as school districts — as property tax.

The short time frame given to accomplish all of this raises the question of the agencies’ ability to make bond payments in time, Kennedy said.

The oversight boards will be charged with selling RDA assets, which will be divided among the local taxing agencies, as well as distributing affordable housing money.

California redevelopment agencies were required to use 20% of revenue for affordable housing development. That usually creates two different revenue streams backing bonds: housing and non-housing.

Redevelopment came under fire partly because other local agencies did not share the incremental tax revenue generated after redevelopment zones were established.

The share of total statewide property taxes collected by RDAs has risen to 12%, according to a report this year from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The end of redevelopment creates potential problems for holders of debt issued by agencies with poor financial standing.

In October, Standard & Poor’s said more than a dozen redevelopment agencies’ creditworthiness were particularly at risk due to the legislation because of weak debt-service coverage and liquidity, while large payments loom.

S&P analysts said the fiscal strain on those agencies would heighten because they would lose the ability to use funds outside of pledged revenue and reserves to cover shortfalls.

The Southern California Logistics Airport Authority had a payment default in December because it said it could not use an intergovernmental loan from the city of Victorville’s RDA to cover its shortfall.

The state treasurer’s office has said it has not had any redevelopment agencies or municipalities contact it about debt problems due to the court decision.

“We retain a strong interest in making sure the credit standing of local issuers is not negatively affected,” said Tom Dresslar, a spokesman for Treasurer Bill Lockyer.

Since doubts about the existence of California redevelopment has been circulating for months, the municipal market has so far been unfazed by the news, said Kelly Wine, executive vice president of R-H Investment Corp., a broker-dealer in Encino, Calif.

The firm’s traders have seen little change in redevelopment bond trading.

“The existing redevelopment bonds are protected in terms of the bondholders,” Wine said.