SAN FRANCISCO — Crushed during the recession, California’s real estate market so far has been spared from a tide of defaults on land-secured bonds — so far.

But the recent default by a community facilities district in San Diego County may raise the specter of more bad debt in the multibillion dollar market for such bonds.

Community facilities districts are normally created in undeveloped areas to fund roads and other infrastructure to support new development.

Even though the vast majority of the land-secured debt sold under California’s Mello-Roos bond law is likely in the clear, the state’s long economic doldrums, and the years of lag time before struggling districts default, may point to more trouble ahead.

A lack of transparency in the land-secured bond market makes predictions tricky. The bond typically are not rated so they are not reviewed by rating analysts.

Borrego Water District Community Facilities District No. 2007-1, located in the desert outside of San Diego, recently defaulted on $9.5 million of Mello-Roos bonds issued in 2007, the first such default this year and only the third since 2007.

With a slew of dirt-bond defaults in Florida, worries persist about whether Borrego is a harbinger of a similar wave in California.

“Most of the Mello-Roos districts are in pretty good shape. The ones that are questionable are the ones that were issued in 2006 or later,” said A. L. “Bud” Byrnes 3d, CEO at RH Investment Corp. in Encino, Calif. “There is a potential for a problem that may well be festering but we won’t know until next year or later this year.”

Localities have issued $6.55 billion of Mello-Roos bonds since the beginning of 2006, of which $5.59 billion are still outstanding, according to Bloomberg.

Byrnes said community facility district bonds issued in 2006 or later could be in trouble because it can take three to five years before a district starts showing signs of distress amid a dire housing market.

The current Mello-Roos market may resemble the 1989 to 1993 period when land-secured bonds also came under pressure because of a falloff in the housing market. It took several years for bonds to show signs of trouble after the housing market fell apart.

Defaults and reserve draws surged in the early and mid-1990s. Draws on reserves peaked at 44 in 1995-96, followed by a peak in defaults at 29 in 1997-98, according to a 2008 report by the California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission.

“Typically, the majority of problems that have cropped up in the Mello-Roos arena really have been experienced in districts that have a small number of property owners,” said Tom Dresslar, a spokeman for the California treasurer’s office, which operates CDIAC.

The report said community facility districts’ draws on reserves and defaults could increase for land-secured debt issued in the last few years because of a spike in home foreclosures.

“Any problems that are out there that we are unaware of now may not have hatched yet,” Byrnes said. “They are still incubating.”

California created Mello-Roos districts — named after the two lawmakers who sponsored the enabling legislation — in 1982 to finance infrastructure in the wake of the passage of Proposition 13 property tax limits.

Mello-Roos bonds are the most common land-secured bonds issued now in the state. Special tax-assessment district bonds tied to legislation passed in 1911, 1913 and 1915 — so called “1915 Act” bonds — are less common and usually issued in smaller denominations.

Mello-Roos districts can issue tax-backed bonds for infrastructure with the approval of either two-thirds of the residents of a district or two-thirds of property owners in districts with fewer than 12 residents.

Often they are issued by districts owned by real state developers, with the proceeds used to build infrastructure such as streets.

Daniel Bort, an attorney with Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe in San Francisco, who advises Mello-Roos issuers and worked on the first issue in Northern California in 1985, said the majority of the bonds are fine but agreed problems could be lurking.

“There are going to be districts from the very, very secure, secured by, say, thousands of owner-occupied homes, all the way to the other end of the spectrum with no vertical construction secured by a single developer who is in trouble,” Bort said. “As the stress level gets higher on property developers, there could be others that fall in on that side of the line.”

Bort said the most vulnerable issues would those done just before the recession started and with low value-to-lien ratios.

He said the districts with the highest risk are also in areas devastated by unemployment, resulting in higher tax delinquencies.

The unemployment rate in California was 12.3% in December, according to the U.S. Labor Department. The rate is much higher in parts of the Central Valley that experienced a lot of residential growth during the real estate boom — Merced County’s jobless rate topped 20% in December. Property values in the valley were crushed by the sharp real estate downturn.

The question is how many troubled tracts carry Mello-Roos bond debt?

California new housing starts were down 277% at 2,632 in November compared to 9,932 in the same month in 2006, according to the latest figures available from the Construction Industry Research Board.

Typically investors become very worried when delinquencies in districts reach above 10%, Byrnes said.

Transparency in the market is also a concern.

Since property taxes are collected from special assessment districts in December and April. No reports are issued related to the December collections so no new information is available until April reports are released in June.

If a high percentage of property owners are delinquent on taxes in a district, it takes a long time for that information to become public.

“A way we can discern whether there is a problem is if their filings are over a year old… then you might have a problem,” Byrnes said, referring to disclosures on the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s online EMMA system.

Because Mello-Roos bond issues are typically unrated and relatively small in size, there is little published research and information on them.

The California’s treasurer’s office tracks dirt-bond defaults and draws on reserves, but the list is voluntary.

According to CDIAC’s list of distressed community facilities districts, six have defaulted on Mello-Roos debt and 21 have drawn on reserve funds since 2006.

The defaults included districts in Los Angeles County in 2006, San Diego in 2007 and Nevada County in 2006. The only defaults last year were in the troubled rural areas of Lathrop and Chowchilla.

In the most recent default, the Borrego district did not pay a February interest payment of $267,950. Like almost all defaults on Mello-Roos bonds, the district suffered a dearth in tax collections because of foreclosures.

It issued $9.53 million of unrated Mello-Roos bonds in 2007 to refinance bonds issued to build infrastructure for a golf community in the desert.

The district’s tax delinquencies rocketed to 86%, or $593,000, in fiscal 2009-2010 from 0.14%, or $787, in fiscal 2008-2009. The district made its first unscheduled withdrawal from the bond reserve fund a year ago, leaving $543,000 in the reserve, according to filings.

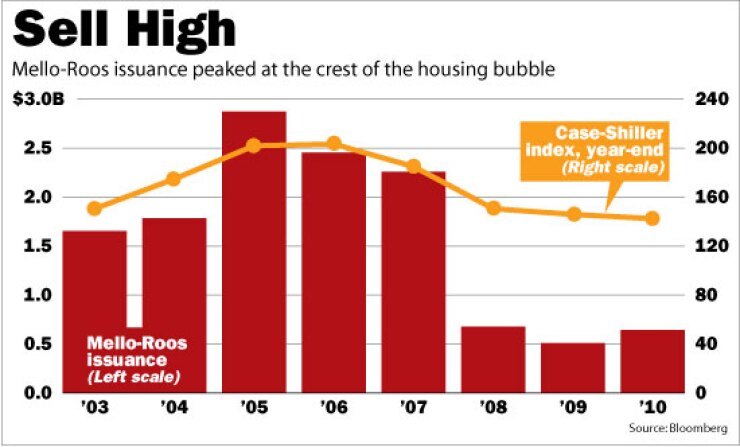

A slide in Mello-Roos issuance may also limit the number of future defaults.

Only $178 million of new-money land-secured debt was issued in fiscal 2009, according to CDIAC, down from $2.3 billion in fiscal 2007 and almost $3 billion in fiscal 2006. It’s the lowest level reported since CDIAC began collecting the data in 1994.

Even when a district defaults, bondholders are not likely to lose their everything because the Mello-Roos bonds are secured by real property that is subject to foreclosure.

To increase security of the bonds, state lawmakers have given districts enhanced tax-foreclosure powers. Delinquent taxpayers can lose their homes in as little as a year in a Mello-Roos district, much quicker than it takes authorities to complete a tax foreclosure elsewhere.

“The foreclosure sale only has to bring enough for the delinquent taxes,” Bort said. “It is not going to be a total loss and ultimately possibly not a loss at all to the bondholders.”