WILKES-BARRE, Pa. — As black clouds and threats of rain and heavy winds hovered over downtown Wilkes-Barre, Mayor Tony George spoke of “the perfect storm” that has engulfed his city’s finances.

“Clearly we are not in an enviable position,” George said at a state Department of Community and Economic Development hearing at City Hall on Aug. 1 to consider Luzerne County seat Wilkes-Barre’s request for distressed status under Pennsylvania’s workout program for municipalities, known commonly as

While the DCED has 30 days to act on the request, distressed status appears a formality.

“Wilkes-Barre has exhibited conditions that make it difficult to fulfill its responsibilities and provide for the health, safety and welfare of its citizens,” said James Rose, a local government policy specialist at the DCED’s Governor's Center for Local Government Services.

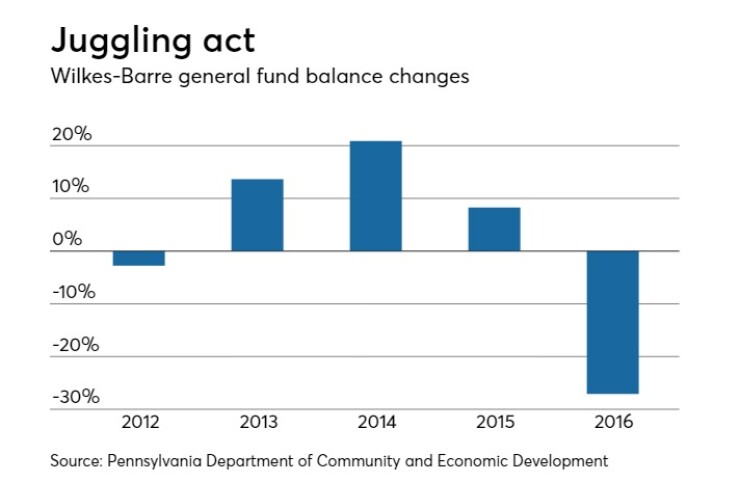

Rose cited a continued pattern of year-end deficits, cash-flow difficulties, negative demographic trends and “significant structural deficits" projected for the out years.

George projects a $3.5 million shortfall for fiscal 2019. According to a DCED overview, the cumulative gap could spike to $16 million by 2021.

The city’s approved fiscal 2018 budget totaled $49.5 million.

More broadly, 40,600-population Wilkes-Barre’s struggles reflect those of northeast Pennsylvania’s declining coal region.

“When you compare Wilkes-Barre to Hazleton and Scranton, they’re caused by the same types of problems, declining demographics and the end of coal,” said Alan Schankel, a managing director at Janney Capital Markets in Philadelphia.

The mining and manufacturing boom boosted Wilkes-Barre’s population to 86,000 in 1930. The decline of those industries over the decades — intensified by the 1959 Knox Mine disaster that killed 12 people — effectively whittled it to about 40,600 today.

Statewide, 44 of Pennsylvania’s cities, or 77.2%, have decreased in population size since 2010, said the Wilkes-Barre-based

As mountains hover, historic buildings dot lengthy Wilkes-Barre Boulevard. Places named Coal Street Park and Anthracite Newstand, the latter near the diamond-shaped Public Square downtown, speak to the region’s history.

Hazleton, also in Luzerne County and under Act 47, filed its recovery plan in May. The city council is considering it. Scranton, 20 miles northeast of Wilkes-Barre and the seat of Lackawanna County, has been in the workout program since 1992 and expects to exit next year.

On July 6, about a week after Wilkes-Barre filed under Act 47, S&P Global Ratings placed the city's long-term rating and underlying rating of BBB-minus — barely above junk — for the city’s general obligation bonds on credit watch with negative implications.

"We could lower the rating if we believe that the city's credit quality is no longer commensurate with the rating," said S&P analyst Moreen Skyers-Gibbs.

Neither Fitch Ratings nor Moody’s Investors Service rate the city.

Wilkes-Barre in March 2016 entered an early intervention program, which state lawmakers formalized four years ago as part of the DCED Act 47 process. Through a request-for-proposals process, it hired Public Financial Management and McNees Wallace & Nurick LLC to provide an evaluation.

The city issued $52 million of bonds two years ago to refinance debt and adjust balloon payments to level, and tapped minimum municipal obligation relief under state law to reduce its 2017 pension payment to $5.6 million from $6.5 million. That latter provision expires this year and the city's MMO payment will spike to $7.1 million in 2020.

"It became apparent that the city did not have the staff or funds to begin implementation" of some of PFM's recommendations, the DCED said in a report.

The five-member city council has balked at tax and fee increases and rejected a $2 million sale of the Park & Lock East garage.

Also relevant to Wilkes-Barre’s distress, said DCED, are a stagnant tax base, a continued decline in pension assets to satisfy long-term liabilities, comparatively low median household incomes, unemployment and high crime rates.

Wilkes-Barre's pension funding ratio has dipped to 62% in 2015 from 73% in 2011.

“Without an improved position, it is likely that the city’s pensions will remain moderately distressed, and possible that certain conditions, such as a dip in the stock market, could lower funding to the severely distressed level,” said DCED.

Municipal labor unions have stalled on concessions.

In addition, the city has sustained a $228,000 net loss in real estate property the past four years, according to George, largely due to the expansion of Kings College and Wilkes University. More than a quarter of the city’s real estate, or 26.9%, is tax exempt based on county assessments.

George also cited next year’s expiration of a $350,000 Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response grant — called SAFER. And looming for 2019, he said, are a 3% wage increase for city employees and $500,000 in capital improvement needs.

“We are not as bad off as some of the towns that come before you, [but] without the help of Act 47, we could possibly be one of those towns,” George told the DCED officials.

Local property owner Tom Dombrowski urged city officials to sell the 200-acre municipal golf course and 340 surrounding acres.

“You have a major asset here which you’re holding onto,” Dombrowski said. “The golf course alone could bring in $3 million to $4 million. There are courses that have been sold locally in the last five or six years for easily that.

“The land surrounding it is a gold mine if it was marketed the correct way,” Dombrowski added. “You’re missing something that’s worth between $6 million and maybe $12 million to $15 million, and you have to be aware of that.”

Schankel called one-time measures counterproductive.

“Selling land is a classic example,” he said. “In general, I like to see them not resort to selling land. Once you do it’s tough getting it back.”

Public golf courses are financial black holes, according to David Fiorenza, a Villanova School of Business professor and a former chief financial officer of Radnor Township, Pa. He consulted for two municipalities that owned them.

“Very seldom do golf courses, swimming pools and community centers generate enough cash to break even," Fiorenza said. "This is a good market for Wilkes-Barre to sell this asset, but the political ties may be stronger than we think for this ailing city.”

George, a lifelong resident, former police chief and former city council member, began his four-year term in January 2016.

“I saw what they were doing wrong,” he said after the hearing at the fourth-floor city council chambers. “They were stuck in the old regime. The city will be back.”

Former York, Pa., Mayor Kim Bracey conducted the hearing. Bracey, who lost her re-election bid last year, is now the executive director of the Governor's Center for Local Government Services, a DCED unit.

Bracey's involvement, according to George, is a plus. “She knows about all our problems.”

Act 47, named after the enabling 1987 legislation, has 17 communities now under DCED watch; 14 have exited, including Pittsburgh earlier this year. Program benefits, according to Schankel, include debt restructuring, zero-interest loans, outside professional consulting and special taxing authority.

“You have to plan for getting out,” said Schankel. “Like a drug, you have to wean yourself off.”

On Thursday, the DCED tweaked its recommendations for Harrisburg's exit plan, allowing the capital city to keep its higher local services tax for two more years. DCED scrapped its calls for a 105% increase in property taxes.

According to Fiorenza, Wilkes-Barre could try to attract businesses that seek to partner with area universities and community colleges.

“However, one of the continuing concerns will be the high earned income tax and business privilege tax the city imposes on businesses and their employees,” he said. “This is their biggest deterrent.”