New York’s mass transit crisis has prompted some transportation advocates to argue the city would be better off taking back subway and bus operations from the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

They say 50 years of state management of city transit hasn't worked and their movement, however politically difficult, is not just blowing off steam amid widespread breakdowns, delays, overcrowding, political bickering and tales of woe about MTA finances.

“This is not an overnight fight,” said Bradley Tusk, a venture capitalist and former political operative. “But do I think that this could be the rallying cry for the mayoral campaign in 2021? Absolutely.”

Tusk spoke last Monday night as about 100 people met at the Lower Manhattan headquarters of the nonprofit advocacy group TransitCenter to discuss building momentum for the change.

The MTA, one of the largest municipal issuers with roughly $41 billion in debt, has long been at the core of city-state wrangling, including the current rift between Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio. Trigger points have ranged from Cuomo’s intrusive management style to the state’s periodic raids on transit accounts to balance its own general fund.

MTA Chairman Joe Lhota, speaking at Wednesday’s board meeting, said unplanned fare hikes and draconian service cuts could materialize without new revenue sources.

“Unless we get a sustainable new source of revenue, we have no other options to balance our budget after 2019,” Lhota said. The authority's biennial fare and toll increases, implemented since 2010, and any Manhattan congestion pricing plan may not provide enough funds, he added.

S&P twice this year

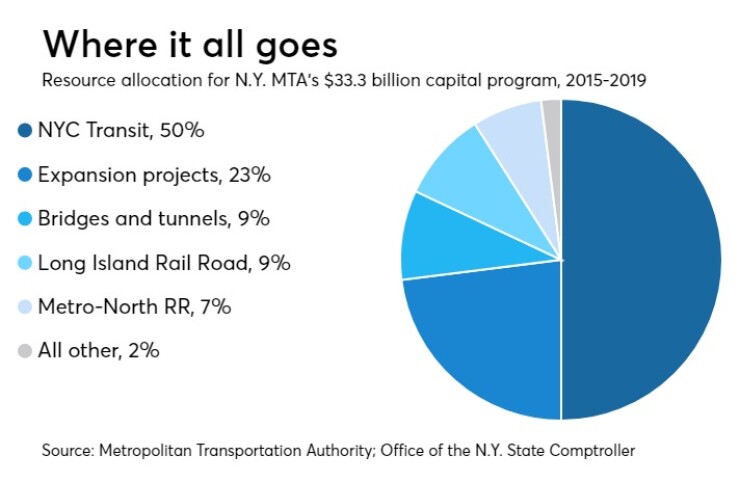

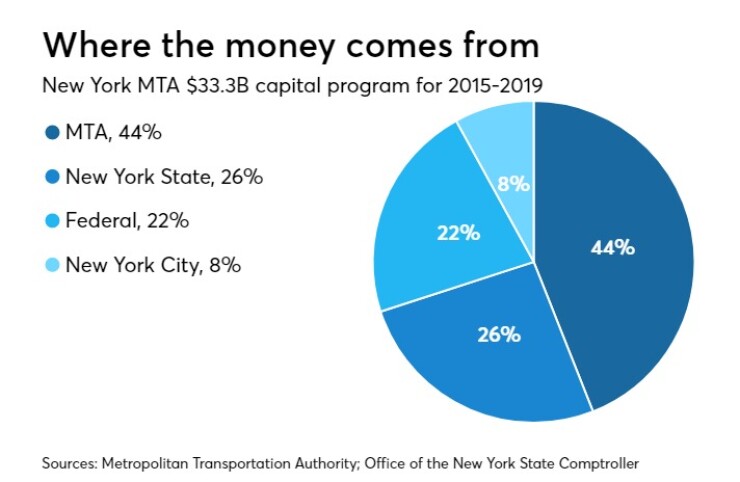

New York City Transit, which operates the subways and buses, accounts for roughly half the MTA’s $33.3 billion capital program for 2015-2019. About $3 billion of the capital plan is self-generated through bridge and toll revenue.

Andy Byford, president of the MTA’s New York City Transit division, said his so-called Fast Forward triage-and-modernization initiative could cost $40 billion over 10 years. He is lobbying for city, state and federal support and has called on the MTA board to advance its 2020 to 2024 capital program.

Firing away at the MTA has long been a sport of choice. Former Mayor Ed Koch, for example, called for its abolition in 1983. “It was too inviting a target not to attack,” former MTA chairman Richard Ravitch wrote in his book, “So Much to Do: A Full Life of Business, Politics and Confronting Fiscal Crises.”

A state-run agency serving a city whose 8.6 million population amounts to 40% of the state’s population provides an inherent disconnect. The state legislature essentially allocates few statewide revenues to the MTA, but enables local and regional taxes.

When subways fail, “that state senator from Batavia is about as likely to pay the political consequences as the premier of Saskatchewan or the king of Thailand,” said TransitCenter executive director David Bragdon.

Chicago, he said, has benefited from strong city representation on the Chicago Transit Authority board.

“Illinois has one of the most corrupt state governments in the country, but the clown show that goes on in Springfield has only a limited impact on transit in Chicago,” Bragdon said.

Los Angeles County and Seattle’s Puget Sound region have the nation’s two largest transit capital plans. Locals control both boards.

“The residents and leaders of Los Angeles County do not go to Sacramento to ask to be given permission to basically spend their own money in their own community,” Bragdon said. “The leaders and residents of Seattle do not have to go down to Olympia and make all kinds of silly and crazy deals in order to manage their own transit system.”

Prying away state control in New York is a tall order, according to Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management.

“The state likes to have the city as a vassal of it,” Cure said.

City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, a possible mayoral candidate in three years, has said he would favor the city riding solo on a congestion-pricing package, which to date has stalled in the legislature.

Tusk, campaign manager for New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2009 and a former Illinois deputy governor and ex-communications director for U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer, cited as precedent the city’s decade-long battle to wrest control of its public school system from the state.

“You need one person, whether it’s Byford or whoever, who reports to the mayor, just like the police commissioner, just like the schools commissioner,” said Tusk. “We can work out the rest — funding mechanisms, governance. The MTA is not the law of nature. It’s not the 10 commandments. It’s a series of old laws that came to us because they made sense politically.”

Cure sees a higher degree of difficulty in obtaining transit autonomy.

“I think it would be really difficult to do compared with, say, the school education department,” Cure said. “With the schools, the city pays into a general fund, and they formulaically get an amount like other school districts. You could say the city gets shortchanged, but it’s still a well-established fund. The MTA is different.”

In addition, Cure said, state officials have limited city use of design-build project delivery and public-private partnerships, and Albany would also have to approve special taxes the city might need to effectively operate NYC Transit.

Other variables would include revenue from bridge and tunnel crossings and commuter rail ridership within the city's five boroughs.

Cuomo, who controls a plurality of seats on the 17-member MTA board, has tightened his grip over the authority the past two years. He declared a state of emergency for the system in June 2017 and has imposed such initiatives as a technology “genius challenge” that invited proposals from outside firms and rankled in-house engineers.

Ravitch called on MTA board members to step up, saying the board is responsible for the system’s well-being.

“The law makes it very clear,” he said on a recent

“Whereas the city owned the subways prior to the creation of the MTA in 1968, and whereas the city has always contributed one way or the other to the financial needs of the system, the responsibility has not been primarily that of the city. It’s been paid for far more over time by the state, by the region, by federal contributions, and starting with what I initiated in 1981, borrowing against the fare revenues and issuing debt," said Ravitch.

“The governor has decided that he wants to run the MTA. The fact of the matter is that the MTA is run by the second floor at the capitol [in Albany] because the board members are willing to do it that way. That’s their fault, not his.”

In the 1960s, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller created a regional authority, the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority — now the MTA — that subsumed then-bankrupt Long Island Road, plus New York City Transit and the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which operates water crossings.

Absorption of the latter was a knockout punch to Robert Moses, the decades-long city power broker whose TBTA chairmanship was the last of his 12 leadership posts.

In the 1960s, Mayor John Lindsay, whom Rockefeller dwarfed politically, saw a carrot in a $2.5 billion state bonding package for multimodal transit that included aid to the city’s deficit-ridden system. City Hall and Albany worked out a funding package that included about $600 million in state funds from that bond package. The city would shoulder a further $700 million.

The city, meanwhile, had commenced its financial slide that spiraled to a near-bankruptcy in the 1970s. “The city’s finances had begun to weaken, but not everyone recognized it,” said Peter Peyser, a former Koch operative and founder of consulting firm Peyser Associates LLC.

A city comptroller’s report in 1966 cited “ability to access debt” as a benchmark for the city’s fiscal health. “They weren’t measuring fiscal health by the city’s budget imbalance,” Peyser said.

Political variables in the wrangling for the MTA’s inaugural five-year capital program in 1981 ranged from the degree of Republican suburban support for Long Island Rail Road funding to the backing of the “Westway,” a planned but never-built West Side expressway.

Ravitch himself took three of the city’s top executives, David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan, Dick Shinn of Metropolitan Life and Bill Ellinghaus of AT&T, on a pre-dawn tour of decrepit rail yards, prompting their support for a tax package in Albany.

“The funding questions are really important when we’re looking at the governance system. How does that functionally play out?,” said Rachael Fauss, a senior research analyst for the nonprofit Reinvent Albany.

A city agency, she said, could invite better scrutiny from the city and state comptrollers and the City Council. The move could also open upzoning possibilities through transit-oriented development, akin to the Bloomberg administration’s Hudson Yards development site that included the extension of the No. 7 subway line westward from Times Square.

“The notion of value capture for expansion of mass transit is worth pointing out,” Jonathan Ballan, a Cozen O’Connor co-chair of public and project finance, said at Wednesday’s Bond Buyer Mid-Atlantic Municipal Market Conference in Philadelphia.

“Tax-increment financings are very important,” said Ballan, a former MTA board member. “Little things maybe like naming rights. You have to wonder why a mass facility going to a major arena or whatever doesn’t lead to more revenue for the mass transit agency for naming rights or something like that."

Byford, meanwhile, continues to push Fast Forward, through town-hall type sessions across the five boroughs and even during a segment on the CBS news magazine program “60 Minutes.”

Veronica Vanterpool, an MTA board member and former executive director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, said the authority is publicizing itself better.

“Coming from the advocacy community, I think the MTA has done a horrible job of advocating for itself, over at least my 11 years in advocacy,” she said. “But I've seen that shift significantly.”