Already struggling under the weight of burdensome pension tabs, Illinois and many of its local governments face even more damaging wounds from the COVID-19 pandemic, raising rating, solvency and bondholder risks.

That’s the assessment offered by Moody’s Investors Service in a grim report that will fuel worries over how the state and local governments will manage the revenue blows imposed by the pandemic and potentially higher payments depending on investment performance.

"Illinois' already high pension-related credit risks have been compounded by the coronavirus-induced revenue shock," said analyst Tom Aaron, who is named along with Timothy Blake as an author of the report. “The substantial unfunded retirement liabilities accumulated by the state of Illinois and many of its local governments will weigh more heavily on their credit profiles with expected revenue declines stemming from the coronavirus economic downturn.”

Illinois governments can’t cut benefits due to the state constitution’s ban on impairing or diminishing promised benefits and some governments risk pushing their funds to insolvency if they pull back on funding contributions.

The protections afforded not only to accrued benefits but to future benefits for current members were reinforced by Illinois Supreme Court rulings on state pensions in 2015, Chicago pensions in 2016 and the Chicago Park District in 2018.

Local governments also face the diversion of revenues that flow through the state under an intercept mechanism if they fail to make actuarial or statutorily required contributions.

“And some governments, both large and small, have little flexibility to pull back on contributions without risking the solvency of their retirement systems,” Aaron said. “As a result, pension-related credit risks are higher today than during the last recession.”

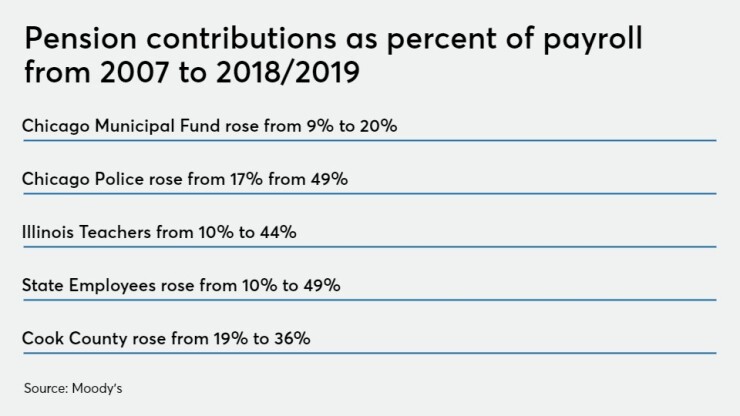

Many economists and revenue forecasters trying to assess the damage of the economic shutdown to slow the spread of COVID-19 are drawing comparisons to the impact of the 2008 Great Recession. Such a comparison for Illinois and local governmental pensions falls short of capturing the potential funding burden because contributions are consuming more of budgets than they did in the last recession.

“Across the vast majority of the largest retirement systems in the state, government contributions are significantly higher relative to payroll than in 2007,” Moody’s wrote. “Many Illinois governments risk severely hampering future pension asset accumulation if they pull back on contributions.”

Moody’s cites as an example the state’s Teachers Retirement System with contributions projected to steadily rise to almost $11 billion in fiscal 2045, compared with $4.8 billion in fiscal 2020. In a hypothetical stress test scenario where the state simply freezes its contributions at fiscal 2020 levels, Moody’s warns of a 50% chance the system would deplete its assets by the mid-2040s.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker said Monday he intends to make the state’s full statutory contribution — which is the required legal payment but falls short of an actuarially required contribution (ARC) — when he was asked to comment on the report’s warnings. Illinois has reported a $137 billion unfunded liability and collective 40% funded ratio.

Local governments outside Chicago must fund their pensions at an actuarial level or risk revenues that flow through the state being diverted at the request of their local public safety funds or the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, which covers general employees.Chicago now makes ARC payments for its police and fire funds and is ramping up to ARC-level payments in 2022 for its other two funds that cover general municipal members and city laborers.

State leaders have not suggested a change in funding requirements, but Moody’s warned that if such a step were taken to provide relief, it “could significantly constrain pension asset accumulation and, in the most severe cases, risk pushing retirement systems into insolvency.”

And moves by especially strained local governments to push off contributions that trigger the intercept add to risks that bondholders will take a backseat to funding demands for pensions and critical services.

“In an extreme example with numerous defaults over several years, this revenue diversion has prioritized pension solvency and minimum municipal service delivery over general obligation bond debt service,” Moody’s warned.

One example is the distressed Chicago suburb Harvey. Its public safety funds sued and sought to use the intercept mechanism. Harvey is making contributions under a settlement agreement. Bondholders have since sued as the city remains behind on defaulted debt service. The case is pending. A handful of other pension funds have used the intercept that is managed by state Comptroller Susana Mendoza.

Near-term solutions to avoid the intercept have exacerbated the struggles for some. The Ba1-rated suburb of Oak Lawn reached an agreement with its pension systems to avoid a diversion provided the village increases contributions by roughly $1 million annually. “Whether the village's pension systems will continue to abide by the agreement is a risk to the city's near-term finances,” Moody’s said.

Baa1-rated Granite City issued pension obligations bonds and rather than deposit all proceeds into the system it withheld a portion to help fund its annual contribution requirements. Moody’s called it a strategy viable only until the proceeds are exhausted.

Chicago

Chicago's pension challenges are even more severe than the state's because of the magnitude of its annual tread-water gaps and their precarious funded ratios, Moody’s warned. The city’s funding schedule targets a 90% funded ratio for two funds in 2055 and for all four by 2059. It will take a decade before it begins to cut unfunded liabilities.

Chicago has reported a $30 billion net pension liability and collective 23% funded ratio, although Moody’s puts the liabilities at a higher level based on its formula.

“While there is no indication the city intends to seek contribution deferrals, if it were to freeze its contributions at 2020 levels, it faces retirement system insolvency within several years, at which point its contributions would hit pay-go levels,” Moody’s warned.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot recently said the city will adhere to the current funding schedule when asked what measures might be under consideration to tackle a COVID-19 related deficit.

“Chicago's tax base is also leveraged heavily by the substantial pension liabilities facing its overlapping governments. Numerous governments serving the same population will likely need to concurrently either raise revenues or adjust spending to accommodate higher pension costs, which may be practically and politically difficult,” Moody’s said.

Moody’s puts Chicago's leverage from debt, its pension liability based on Moody’s calculation, and adjusted net other post-employment benefits liabilities at a combined $51 billion, almost $19,000 per resident. The combined leverage of overlapping local governments is $58 billion, more than $21,000 per resident. Add in the state, and the numbers rise to $66,000 per Chicago resident. Of the largest U.S. cities, the next closest is New York City at just over $40,000, Moody’s said.