Deep sighs and “not again” echoed as New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority in late April announced a further $1 billion spike in the cost of the East Side Access project.

According to MTA officials, the latest tab is $11.2 billion and rising -- way up from the ballpark $3 billion then-U.S. Sen. Alphonse D’Amato quoted when he announced his pet project in 1998. That adds up to $3.5 billion per track mile, more than seven times the national average.

The MTA's original estimate was $4.3 billion.

The undertaking, long discussed before D’Amato came forward, is intended to redirect some Long Island Rail Road commuter trains to Grand Central Terminal on Manhattan’s East Side, supplementing service to Penn Station on the West Side and Brooklyn’s Atlantic Terminal.

The expected start date has incrementally moved to 2022 from 2009.

East Side Access has spawned debate about the MTA’s relationship with quasi-federal Amtrak, the authority’s management of capital projects, the cost-inefficiency of its LIRR unit and the need for proper execution of alternative project delivery mechanisms such as design-build.

The MTA is one of the largest municipal bond market issuers with roughly $38 billion in debt.

The overruns have thrown gasoline on the incendiary relationship between the state-run MTA, which Gov. Andrew Cuomo controls, and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, a Cuomo adversary. De Blasio, whose city had to allocate $418 million to the MTA’s subway action triage plan under the fiscal 2019 state budget, called the latest cost spike a “ludicrous story.”

“This is yet another cost overrun, yet another delay in a project that seems to just take up money all the time, but yet the state is asking the city to give money to an agency that clearly does not how to use its money properly and on the right things,” de Blasio said.

MTA capital construction president Janno Lieber said the project is making “significant progress.” Speaking before the MTA board’s capital program oversight committee on April 23, Lieber cited terminal construction, track installation, concourse elevators and the modernization of the Harold Interlocking track junction in Queens.

“We can and should keep the 2022 revenue service opening date but the project is going to require more money,” said Lieber, a Mr. Fix-It of sorts who shepherded Silverstein Properties’ completion of the World Trade Center site.

He told the Long Island Association business group Wednesday in Melville, N.Y., that “2022 is absolutely written in stone.”

To counter the argument that costs could eventually outweigh regional benefits, Lieber and MTA Chairman Joe Lhota are touting the project’s role in tri-state infrastructure, even comparing its importance to the Gateway tunnel undertaking between New Jersey and New York.

Funding for the latter project -- adding two rail tracks under the Hudson River to double capacity -- has long been mired in regional and Washington politics.

“This project in my mind is growing in importance. We’ve learned from Gateway and the whole response to Hurricane Sandy about the necessity of having duplicative cross-river traffic,” said Lieber.

“This project does for the East River what the Gateway project will do for the Hudson River. As difficult as this project has been and continues to be, and notwithstanding some of the disappointments of this project, having it under way at this time, when we see our brethren struggling to figure out how to accomplish Gateway, is I think a significant advantage to the region and to the MTA.”

Operational improvements, said Lieber, include eliminating repetitive testing and forming a dedicated team to manage a streamlined order process and concentrate on “schedule-critical” matters.

A sour relationship with Amtrak has impeded the MTA and LIRR over the years. Amtrak and the MTA share tunnels on both sides of Manhattan.

While LIRR operates most of the trains running into and out of overcrowded Penn Station, Amtrak runs the station, its tracks and feeder tunnels, having taken control of the station from bankrupt Penn Central in the early 1970s.

Onerous Amtrak work rules, prolonged contracting sign-offs and oversight redundancy have compounded the problem.

“Amtrak has not behaved very well,” said

The MTA issued its initial cost projections before even talking with Amtrak. “All the funding in the world wouldn’t have solved the dysfunction between the MTA and Amtrak,” said Gelinas.

Another major cost driver was the decision to tunnel deep underneath the existing Grand Central tracks instead of using the existing platform area, because of a longstanding turf war between LIRR and Metro-North Railroad, whose home base is Grand Central and which serves upstate and Connecticut commuters.

Both LIRR and Metro-North are MTA units.

“Bringing LIRR trains directly into Grand Central would have saved the MTA billions — not least the expense of carting out all that muck,” said Gelinas.

Gov. Cuomo and some MTA board members over the years have called for the authority to take over Penn Station.

Board member Andrew Saul suggested re-examining the original operating agreements.

“We have tons of lawyers around here. They should look at this thing,” he said. “We’re facing huge capital cost overruns here.”

Lhota dismissed the notion of suing Amtrak.

“I’m not particularly fond of lawyers, so the idea of me suing is probably pretty damn low,” he said. “We can negotiate our way through anything.”

According to Lhota, the MTA and other public issuers must estimate costs better, even with the burden of original ballpark figures that are artificially low and politically expedient.

“Look, we have to be better at determining what the cost of a project is going to be,” he said.

“I dealt with this when I deputy mayor. I dealt with this on school construction authority. I dealt with this on the third water tunnel and the [Department of Environmental Protection]. It just was going up and going up. It’s emblematic of something I think that happens throughout government at every level of government, state, local and federal.”

Shaming Amtrak only carries so much weight, said MTA board member and city transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg.

“I’m not saying there aren’t some things they can be doing better, but to me, when I see a project that’s gone up by a billion dollars, I feel we should be in problem-solving mode and not Amtrak-bashing mode," Trottenberg said.

Amtrak’s resources are strained, she added, given its multitude of projects.

“I don’t they’re like willful, lazy people trying to violate a contract. I feel like that’s what’s being implied here.”

Amtrak officials say completing East Side Access will enable it to begin badly needed East River tunnel work.

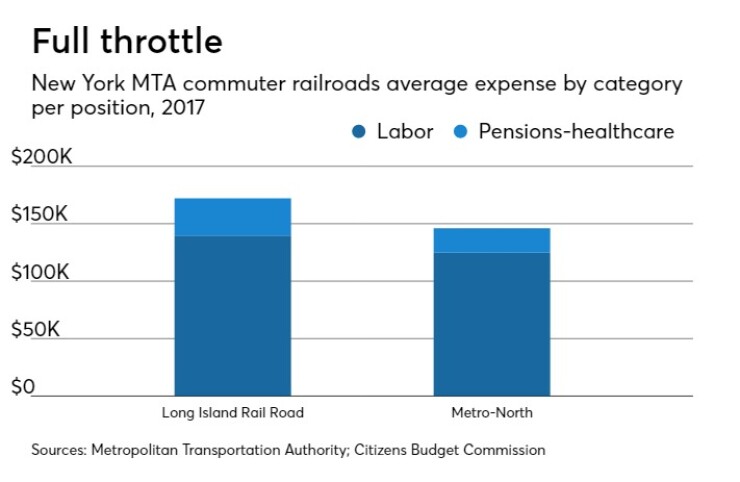

Amtrak and East Side Access aside, LIRR is less efficient than sister railroad Metro-North, said the watchdog Citizens Budget Commission.

In 2017, said a CBC

Aligning LIRR per-mile costs with Metro-North in 2017, said CBC, would have saved $172 million, the equivalent of a 12% reduction in railroad operating expenses in that year.

“A driver of these unit cost differences is the impact of certain legacy costs at the LIRR,” said the CBC’s director of infrastructure studies, Jamison Dague. “Having continually operated since its original charter, the LIRR provides health benefits to a greater number of retirees.”

Additionally, said Dague, LIRR also underwrites a closed and underfunded pension plan that has required significant catch-up payments in recent years. In 2017 its retiree health insurance expense was $60 million compared with $33 million at Metro-North, and payments to cover the unfunded portion of the closed LIRR pension plan exceeded $32 million.

Removing the pension expense related to the LIRR’s closed plan and current retiree health care expenses from unit cost calculations tightens the gap between the two railroads, according to Dague.

“I think the unions would be more amenable as long as they share in the gains, such as savings over 10 years,” said Gelinas. “That’s better than giving them everything or giving them nothing.”

New LIRR president Phillip Eng, though much more low key than his ebullient New York City transit peer Andy Byford, has been just as diligent about his new job. Eng, a Long Island native and resident, station-hopped his first week on the job and got an earful from commuters.

“There were few surprises,” he said.

Eng promised to do his part to improve communications with Amtrak.

“There must be better coordination between our two organizations,” he said. “There has to be a better partnership between Amtrak and the Long Island Rail Road when it comes to Penn Station. Our systems are too interconnected.”