Connecticut’s governor has called for virtually wiping out the state’s rainy-day fund. The mayor of its state capital is putting out feelers for bankruptcy counsel. Legislative gridlock persists as thousands of state employees face layoffs.

Bond rating agencies have hammered both the state and capital city Hartford over the past year. Fitch Ratings on Friday

Connecticut these days is less about yachts and hedge funds and more about comparisons to financial basket cases Illinois, New Jersey and even Puerto Rico.

During a whirlwind week, Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin and the city’s corporation counsel, Howard Rifkin, acknowledged that the city is soliciting proposals for law firms in the event of a Chapter 9 bankruptcy filing.

Gov. Dannel Malloy, meanwhile, called for emptying the state’s reserve fund of nearly $237 million, among other draconian moves, to balance the current fiscal-year spending plan. State budget secretary Benjamin Barnes on May 1 reduced revenue projections by $409.5 million, which created a $389.8 million general fund deficit.

The city essentially is knocking on the door of a house with a bare cupboard.

“Hartford is seeking aid from the state, but Connecticut has its own budgetary challenges,” said Alan Schankel, a managing director at Janney Capital Markets.

Bronin, a second-year mayor and Malloy’s former chief counsel, is facing deficits of $14 million this year and $65 million the next. Large-scale union concessions have yet to materialize and the mayor is seeking $40 million in additional state aid.

“Acting alone, Hartford has no road to a sustainable budget path,” Bronin said in his budget message.

The City Council has until May 31 to act on Bronin’s $613 million budget request.

Moody’s Investors Service in 2016 lowered Hartford’s general obligation bonds to a junk-level Ba2. S&P Global Ratings knocked the city to BBB from A-plus, keeping it two notches above speculative grade.

Rifkin told council members Wednesday that while the city can seek state permission to file bankruptcy, it’s uncertain whether council approval is also necessary.

The City Council in Harrisburg, Pa., also a state capital, filed under Chapter 9 late in 2011, but a federal judge nullified the petition within six weeks, citing the mayor's objections. In Connecticut, Bridgeport declared bankruptcy in 1991, but a federal judge

Also on Wednesday, Malloy announced

They included draining all but $1.3 million of the budget reserve fund, nearly $100 million in revenue transfers, $33.5 million in rescissions and $22.6 million in other actions that include cuts in municipal aid. Only the latter require legislative approval.

“My overriding goal is to solve this fiscal year's potential shortfall without engaging in deficit borrowing, particularly since the economic recovery notes from the 2009 deficit will not be fully repaid until next year,” said Malloy, a Democrat.

The budget office has also begun a contingency plan for laying off state workers.

It gets worse: A possible $5 billion shortfall looms for fiscal 2018 and 2019, the duration of its next biennial budget.

Gridlock reigns at the State House. The Senate is split between Democrats and Republicans 18-18. The Democrats hold a 79-72 advantage in the House of Representatives.

Malloy proposed a $40.6 billion biennial budget in February. The Republicans countered with a $40.3 billion spending plan. Malloy’s plan includes a shift of teacher pension costs to municipalities; lawmakers are resisting.

“This could help stabilize the share of the state's budget devoted to its substantial fixed costs, a potentially positive credit development, although it may pressure local government finances,” said S&P.

Rating agencies cited Connecticut’s persistent budget imbalance and unfunded pension liability in three general obligation downgrades last year as well as Fitch's action Friday.

S&P assigns Connecticut its AA-minus rating and negative outlook. Kroll Bond Rating Agency assigns its AA-minus rating with a stable outlook. Moody's Investors Service rates the bonds Aa3, with a negative outlook. Fitch assigns a stable outlook.

Connecticut headwinds include a sluggish economic recovery, overreliance on Wall Street performance, and high unfunded pension obligations and debt.

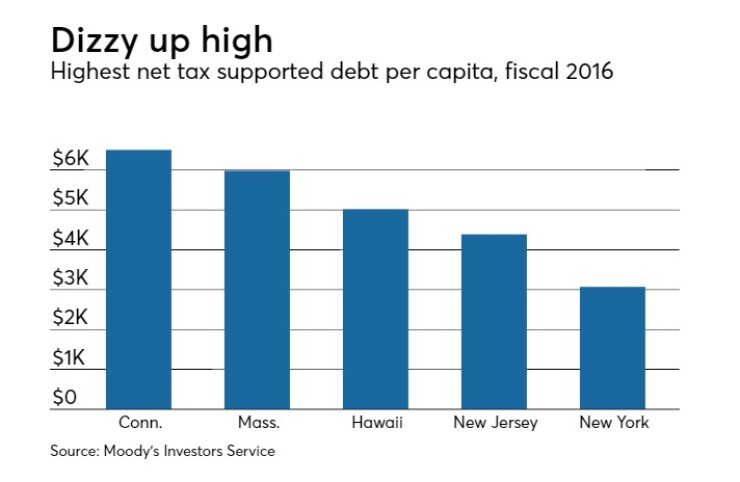

According to Moody’s, Connecticut continues to have the highest debt-service costs as a percent of own-source governmental revenues among the 50 states, even though it declined from 14.3% to 13.3%. Nationally, the numbers remained largely stagnant for the fourth straight year.

By contrast, neighboring Rhode Island’s debt-service ratio has declined to 4.4% in 2016, down over two years from nearly 6%.

“[Rhode Island] suffers from some of the same challenges that plague nearly Connecticut and New Jersey, including an economic recovery that has lagged the nation,” Municipal Market Analytics said in a commentary.

“However, Rhode Island’s credit quality hasn’t suffered the same fate because of stronger budgeting processes and conservative management.”

Proposed remedies are all over the lot.

State Treasurer Denise Nappier has

Other ideas run from restoring tolls on interstate highways for the first time in 32 years to taxing Ivy League Yale University in New Haven.

“There’s a whole lot of stuff being thrown against the wall,” said Tom Schuette, partner and co-head of investment research and strategy at Gurtin Municipal Bond Management.

Toll proponents cite their existence of neighboring states.

"It's just us and Vermont, folks," said state Sen. John Fonfara, D-Hartford, referring to the two New England holdouts.

Republicans question whether tolls would shore up the state's economy. Senate GOP leader Len Fasano, R-North Haven, wanted more conclusive reports.

One study Fasano saw "is nowhere near conclusive on whether or not congestion tolling would bring in any more revenue for the state of Connecticut," he said.

On Thursday, Democratic leaders unveiled what they called a budget-predictability plan.

They said it sets realistic expectations for capital gains and other volatile income tax revenues by permanently capping the estimates and finals, or E&F portion of the state income tax at projected fiscal 2018 levels.

Individuals who do not withhold income taxes pay the E&F portion.

Benefits, they say, include better management of unfunded liabilities, lower fixed costs, net contributions to the budget reserve fund and available savings for capital projects or critical one-time initiatives.

Schuette said not all is lost.

“The state has a history of making tough budget decisions when it’s had to make them,” he said. “It does appear that all the parties are agreeing soberly and clearly that there is a problem. The state has the tools, the appetite and the willingness to deal with them.”

According to Schuette, Gurtin will monitor the teacher pension cost shift, should it pass, for possible strain on local credit.

The Nappier bill, which the legislature’s joint finance, revenue and bonding committee debated, would dedicate a portion of income tax revenues to new investors. Nappier said the strategy would boost Connecticut’s credit ratings and cut borrowing costs.

MMA called the move “a financial engineering gamble,” akin to the Puerto Rico Sales Tax Financing Corp., or Cofina.

“A fundamental flaw in the current proposal, in our opinion, is the suggestion that a new, higher-rated security can be created without having a negative impact on the GO,” said MMA.

“Investors should be wary of conceding yield relative to the GO to purchase bonds under the new program and existing bondholders should expect price weakening as they would see their security diluted as revenues are diverted.”

According to MMA, placing a first lien on the pledged revenues should worry other stakeholders, notably employees and retirees. In addition, municipal aid cuts and state offloading of costs could also compromise municipal credit.

While Puerto Rico’s Feb. 3 filing of a bankruptcy-like Title III petition triggered discussions of similar avenues for wobbly states, Schuette calls such talk “awfully premature.”

David Skeel, a University of Pennsylvania law professor and member of the seven-member Puerto Rico federal oversight board, favors allowing states to file for bankruptcy, but said political pushback stands in the way.

“I think politically it’s highly, highly unlikely,” he said at a Philadelphia Mutual Analyst Society forum. “At this point there’s no constituency for it, so I don’t think it’s going to go anywhere.”

According to Skeel, bargaining dysfunction – both under Democratic and Republican administrations -- holds sway during public pension contract talks.

“Often times the state officials are part of the same pension system or an analogous pension system and they have direct self-interest in the generosity of the pension promises,” he said.