New York's subway crisis has the Metropolitan Transportation Authority looking both outside and within.

Even as the MTA's board on Wednesday approved its $16.7 billion operating budget for 2019 — a plan based on fare- and toll-hike assumptions — the authority faces a raft of uncertainties that range from funding to even the viability of the organization itself.

Moody's Investors Service underscored the sense of uncertainty Friday by lowering the outlook to negative on its A1 rating of the authority.

"We're not folding the tent," MTA acting chairman Fernando Ferrer told reporters after the board OK'd a spending plan that bakes in roughly $270 million for expected biennial fare and toll increases that Gov. Andrew Cuomo said he may not support.

The board is scheduled to vote separately on the increases next month. If approved, they would take effect in March. Officials at the state-run MTA, one of the largest municipal issuers with $40 billion in debt, say the revenue is necessary to balance the budget.

According to Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management, cost containment is as much a problem for the MTA as revenue.

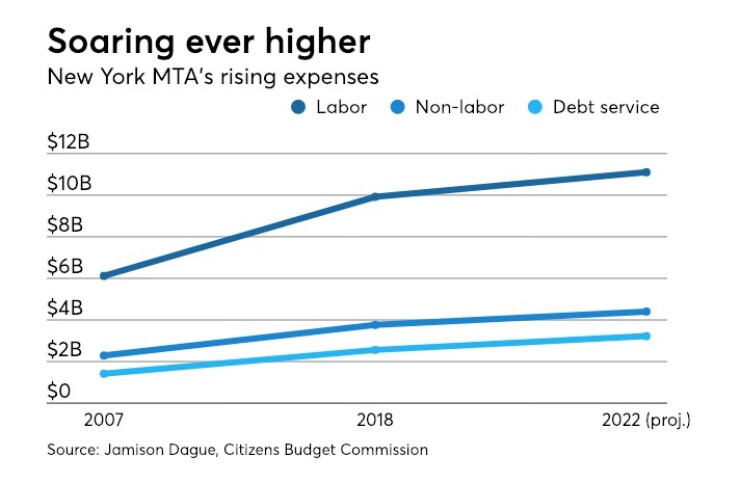

"Clearly they need the money and I don't have much confidence in their ability to contain the expenditure side," Cure said. "Labor contracts are coming due and their capital plans are pretty costly."

Also on Wednesday, the board also authorized the issuance of up to $3 billion in new money bonds and bond anticipation notes for transit and commuter programs, and up to $350 million of new money bonds and BANs to finance MTA Bridges and Tunnels capital projects.

The MTA faces a deficit of up to $1 billion three years out. Its current budget is balanced thanks to one-shots, but the outlook after that is bleak. While ridership figures to rise by only 2% over that period, debt service and labor costs are projected to bump up 6% and 3%, respectively.

"We expect that MTA's financial position will remain very narrow over the next one to two years as the state and city resolve operating and capital support for the system," Moody's wrote to explain its negative outlook. "Without a full funding solution, MTA could turn to additional fare increases or service cuts that would exacerbate negative ridership trends, and its financial position could decline further, resulting in increased leverage position and weakened credit quality."

Board member Andrew Saul issued a dire warning at Wednesday's meeting.

"What we have today, and we have be realistic about this thing, is an operation here that cannot last," said Saul. "This is not going to go on like this and can't go on. I think this board very soon is facing a situation where we are going to have a massive restructuring of the MTA. There's no question about it. You see it coming before us."

Fellow board member Veronica Vanterpool proposed realigning the MTA's budget cycle, possibly as soon as 2020, to synchronize it with those of the state and city, upon which the authority is looking for increased funding. While the MTA's fiscal year begins Jan. 1, the state and city commence theirs April 1 and July 1, respectively.

The status quo makes budgeting a crap shoot, Vanterpool said. "We have an irrational budget process."

Vanterpool and Carl Weisbrod abstained from their budget vote.

"If we vote yes, we're sanctioning a flawed process," said Vanterpool, a board member since 2016. "We're endorsing a series of assumptions that are precarious. But then if we vote no, we are facing an $850 million deficit, potentially, [and] our bond rating is affected."

Vanterpool's proposed change to the MTA bylaws will be up for discussion next month.

"I’m not certain yet," Ferrer said of Vanterpool's idea. "Discussing it for the future, as is I think was her direction, is not a bad thing to do.”

Lisa Daglian, executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA, called the idea "amazing in its simplicity."

With the state legislature set to reconvene in Albany, creative revenue suggestions to backstop the MTA include congestion pricing, marijuana revenue, a millionaire's tax, expansion of transit-oriented development and an outer-borough streetcar.

The MTA operates New York City's subways, buses, Metro-North and Long Island commuter railroads and several intraborough bridges and tunnels.

Amid the calls for new revenue sources, questions surround which if any are workable and can navigate the political quagmire that many critics say is largely responsible for the problem.

"From the revenue side, a lot depends upon the governor and it sounds as though he'll push for congestion pricing," Cure said.

As states begin to pursue options from the legalization of marijuana, New York University's Rudin Center for Transportation said weed could provide the MTA with the dedicated funding source it needs.

"The legalization of recreational cannabis offers New York State a unique opportunity to generate a new revenue stream dedicated to mass transit, said the

"Clearly, increased fares and congestion pricing are insufficient to deal with the long-term financial needs of the subway system. New York State is not a leader, but it need not be a laggard."

They cited Washington state, Colorado, Oregon and California for precedents in determining how to raise revenues through retail and wholesale marijuana taxation.

City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office

"There are a lot of demands on that money; other sets of topics -- healthcare, education and medical -- as well," Cure added.

Congestion pricing would primarily involve a charge on vehicles entering Manhattan south of 60th Street. The MoveNY plan proposed by former city transportation commissioner "Gridlock Sam" Schwartz would toll three now-free East River bridges between Manhattan and Brooklyn while reducing tolls on other intraborough crossings, such as the Whitestone and Verrazano-Narrows bridges.

Schwartz has said his iteration could generate roughly $1.5 billion in pay-as-you-go funding and up to $15 billion through bonding.

With Democrats taking control of the state Senate in January, said Cure, the state could backstop city transit without a plethora of tradeoffs for upstate projects.

De Blasio, while slowly warming up to some form of congestion pricing, still supports his millionaire's tax proposal to help fund transit.

"I just don't think the millionaire's tax will go over well, since the state has to deal with the sunsetting of its own millionaire's tax," said Cure. In addition, he said, new federal restrictions on income tax deductions for state and local taxes would make a tax on wealthy persons politically difficult.

The mayor is wary about real-estate value capture, which he called "the worst idea." The city, he said, would end up shortchanged.

"It takes away revenue that New York City uses right now to pay for schools, police, fire, parks, sanitation," he said. "That money is already locked in to our budget and to our future budget potentially to do the things that people demand of me."

The expected arrival of 25,000 tech jobs to a planned Amazon mini-headquarters in Long Island City, Queens, looms as a wild card for transit, either through direct subsidy from the retail behemoth or value capture from a development multiplier effect.

Queens Borough President Melinda Katz called on Amazon to back de Blasio's stalled $2.7 billion north-south streetcar proposal, the so-called BQX, which they mayor wants to extend from Long Island City to southern Brooklyn.

"The community’s significant concerns about capacity, equity and already-strained infrastructure needs are certainly valid, especially given the substantial tax incentives offered to Amazon," said Katz, who said such a line should include free transfers to MTA subways and buses and reduced fares for lower-income New Yorkers.

The MTA, meanwhile, sputters along through breakdowns and delays while questions about its financial viability linger.

"It's been a neglected system with a lot of competing needs," said Cure. "They have to maintain and improve Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North as well."

Christof Spieler, author of the new book "

"I don't think New York has really taken advantage of the potential of the bus network, either outside the city or inside of it," Spieler, a Houston resident and former board member of Houston's METRO transit system, said during a TransitCenter meeting in lower Manhattan. "I see places like San Francisco that I think have done a lot more to keep buses moving within the city. I see the kind of network redesign that Houston and other cities have done.

"You look at Brooklyn and Queens and there are buses that turn around at the invisible boundary between the two boroughs and you have to change buses to keep going on the same street, because those were two different streetcar franchises a hundred years ago and somehow we have not yet managed to integrate them."

New York, said Spieler, has large untapped potential.

"What I find most depressing about the transit discussion here is that how unambitious it is. It seems like the ambitious discussion in New York City these days is: 'We would like a subway system that's in a decent state of repair.'

"That shouldn't be an ambitious goal. That should be a baseline."