All three branches of the New Jersey government will be talking about the state's unfunded pension liability in the next few months, but many observers doubt whether the problem will be handled responsibly any time soon.

Any failure to handle the issue would be a credit problem for the state. All three major ratings agencies downgraded New Jersey's general obligation bonds to A-plus or the equivalent this spring, pointing in part to the state's failure to deal with pension funding.

In late May Fitch Ratings said that Gov. Chris Christie's proposal to cut the state's pension payment by $1.57 billion in fiscal 2015 was a credit negative. Since then, Christie has used line item vetoes to implement that proposal.

On June 2 Standard & Poor's put its A-plus rating of the state's GO on CreditWatch negative citing, among other things, the state's continued underfunding of its pensions.

The state clearly has a pension funding problem - what is being done to address it?

In the next few weeks most of the action will take place in the courts.

An attorney with a firm representing one of the unions suing Christie over pensions said it would file a new complaint against the governor soon. The case will use the same docket number as the suit filed at the end of fiscal year 2014 on pension funding. It will be heard by the same judge, Mercer County Superior Court Judge Mary Jacobson, he said.

While Jacobson ruled in favor of the governor's curbing of pension payments in fiscal year 2014, she said a 2011 law that implemented a scheduled ramp-up of the state's pension funding created a contractual right for the money to go to the employee pensions. In ruling that the state could breach this contract for fiscal 2014, she emphasized that the state had limited financial options in the few days that remained of the fiscal year to balance its budget, as is constitutionally required.

"A different analysis could very well be required for fiscal year 2015, which will extend until June 30, 2015, and will provide more time for consideration of viable alternatives depending on economic conditions affecting the state," Jacobson wrote in her decision.

In June Democratic lawmakers passed a budget that would have funded the scheduled level of fiscal 2015 pension payments through tax increases. Christie vetoed the tax increases and the pension payments they were going to cover.

The Democrats showed there was an alternate way of dealing with the pension underfunding, said Democratic New Jersey Sen. Loretta Weinberg. The model of this alternate approach will change how Judge Jacobson thinks about the situation, she said.

Along with fighting the unions in court, Christie is expected to open another front on pension funding.

According to a spokesman for the governor, Christie expects to unveil plans later this summer for reduced pension benefits, and thus reduced spending on them.

The Democratic leadership of the New Jersey House of Representatives and Senate have said that they will not consider any revision to retiree pension and health benefits until the state starts following the 2011 agreement on funding pensions, Weinberg said. Weinberg said she agreed with this position.

That 2011 deal, brokered among Christie, Republican legislators and a handful of Democratic lawmakers, exchanged cuts in pension benefits for Christie's promise to increase the portion of the actuarially required contribution the state actually made each year by one-seventh each year for seven years, when it would fully fund the ARC.

How will the suit, governor's proposal and potentially other initiatives play out in the next few months?

Weinberg suggested that the courts may order a resumption of the 2011 ramp up of pension funding.

East Brunswick, N.J. Chief Finance Officer Lou Neely, a New Jersey pension maven, said he thought the union suit would fail.

New Jersey Policy Perspective budget and tax analyst David Rousseau, a former state treasurer, said that Christie has little likelihood of success at reducing the unfunded pension liability. As part of the 2011 agreement the government had promised to contribute $2.5 billion to the pensions in fiscal year 2016. This would be 4/7 of the actuarially required contribution for the year. There is little that the governor could propose that could significantly reduce the size of the actuarially required contribution, Rousseau said.

The governor will also probably make a proposal to cut the other post-employment benefits for the state's retirees, Rousseau said. This mainly consists of health insurance. New Jersey is currently covering the costs of Medicare Part B for its retirees. Christie may propose ending this, Rousseau said.

What to do about the pension reform "will be a contentious drawn-out dog fight between the employees and Christie," Adam Weigold, vice president at Eaton Vance Investment Managers, which manages $1.2 billion in New Jersey bonds and notes. Reducing pension benefits would be politically and perhaps legally difficult, he said. Raising taxes would be politically even more difficult.

Weigold said he anticipated that there would be no solution in the near term. But not funding the pensions "digs a deeper hole every day." The unfunded liability will grow to the point that the pension expenses will have to be cut, he said.

Neely said the state should sell a bond to cover the pension liability. This would reduce the government's total payments ultimately, he said. While the state feels free to not make its pension fund payments, it would not avoid making bond payments, he said.

However the issue is ultimately resolved, New Jersey has a big problem, though not as big as some states.

In May Fitch Ratings said New Jersey had the 10th largest unfunded pension liability in the country among the 50 states, as a percent of personal income. In January Moody's Investors Service said New Jersey's adjusted pension liability was the 16th largest among the 50 states as a percent of personal income.

Fitch said the state's Fitch-adjusted pension unfunded actuarial accrued liability was $45.3 billion. Moody's said the state's adjusted net pension liabilities were $58.5 billion.

New Jersey also has large liabilities for unfunded Other Post Employment Benefits. These are 10.3% of state personal income, Janney Capital Markets reported in June.

There is minimal legal protection for OPEBs, said Janney managing director Alan Schankel said. State governments have a comparatively easier time cutting them than cutting pensions.

Pew Charitable Trust senior researcher David Draine does not see it this way. A recent court decision in Illinois showed that there may be some legal protections for OPEBs, he said.

Rousseau said New Jersey's pension problem has been developing for a long time. The problem started in 1997 when Gov. Christine Todd Whitman chose to sell a roughly $3 billion bond to pay off unfunded pension liabilities. This started a pattern of not responsibly addressing the pension funding gap, he said.

In the following years the stock market rose and the pension funds were over-funded.

In 2001 a new Republican governor, Donald DiFrancesco, got approved a 9% increase for pension benefits, including for those already retired, Rousseau said. In the meantime, the government was not making payments to the pension funds.

When the stock market went down with the end of the dot.com bubble, the pension funds contracted. The governor at the time, Jim McGreevey, who took office in 2002, felt budget pressure in the aftermath of the 2001-2002 recession and did not make full pension payments for several years.

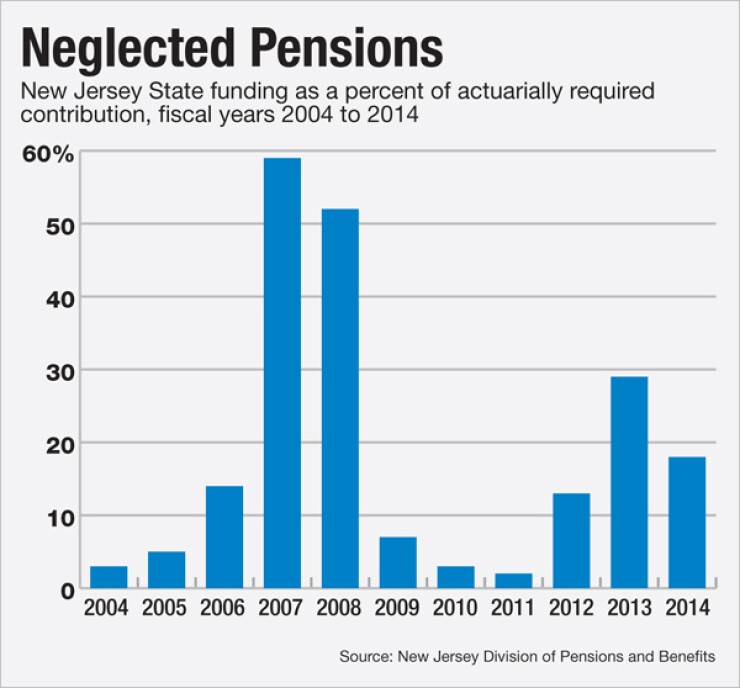

Gov. Jon Corzine, for whom Rousseau served as Treasurer, came into office in 2006. In fiscal year 2007 the state made about 60% of its actuarially required contribution to the state pension funds. In fiscal year 2008 New Jersey contributed $1.1 billion into the pensions, or about 51% of the ARC.

The government also planned to contribute about $1 billion in fiscal year 2009, Rousseau said. The Great Recession hit and because revenues declined the state decided to not make most of its budgeted payment. Because of the recession's impact, the state also did not make the fiscal year 2010 pension payment.

Corzine twice increased the retirement age, Rousseau said. Corzine also capped the salary covered for pensions and increased employee contributions.

The state's pension funding shortfalls in 2010 led the Securities and Exchange Commission to charge New Jersey with violating securities fraud laws by failing to disclose to bond investors that it was underfunding its two largest pension plans. It settled the case -- the first ever brought against a state -- without admitting or denying the SEC's findings and agreeing to cease and desist from any further violations.

When Christie was elected he said he could not afford to make a payment in fiscal year 2011, leading to the pension funding deal.

This winter Christie changed course and said that following the 2011 deal would crowd out other state needs. He said he would spend the remainder of his term focusing on reducing the costs of pensions. Rousseau said that the state's unexpectedly slow economic recovery pushed Christie to this position.

Then the state found April revenue collections far below expectations. To achieve a balanced budget in fiscal year 2014, Christie had the state cut $884 million from planned contributions to the pension fund.

The unions sued to restore the funding but Jacobson rejected their request for relief. Now the unions will sue again shortly and the outcome may be different.