Most municipal bond exchange-traded funds in the fourth quarter performed noticeably worse than the indexes they were designed to track. Or, depending on your perspective, they performed noticeably better.

“Tracking error” — the term ETF managers use for the magnitude of the mismatch between ETF returns and returns on a target index — was substantial in the fourth quarter as the equity market dumped shares representing ownership of trusts filled with municipal bonds more severely than the market dumped the bonds themselves.

Shares of the iShares S&P National AMT-Free Municipal Bond Fund — which with $1.91 billion in assets is by far the biggest muni ETF — underperformed their benchmark index by 137 basis points in the fourth quarter, according to a Bloomberg LP total return calculation that assumes reinvested dividends.

Van Eck Global’s high-yield muni fund’s shares missed their target index by 150 basis points.

Whether the underperformance is a black mark on the still-young municipal ETF industry is subject to interpretation.

While ETF managers are never happy about failing to track their indexes, some hold out the possibility that the turmoil in the ETF market better reflected the illiquidity and evaporation of demand in the municipal bond market than the indexes themselves did.

In other words, the funds underperformed their indexes because the indexes were too slow to recognize how bad conditions in the municipal market were.

“Muni ETFs definitely seem to be precursors reflecting expectations of the muni market, especially in the fourth quarter,” said Phil Fang, who manages the municipal ETFs at Invesco PowerShares. “We believe that muni ETFs can reflect the expectations of the muni market ahead of it.”

In that sense, the more dramatic sell-off of municipal ETFs may have been presaging further weakness in municipal bonds, as well as manifesting weakness in the bond market that wasn’t showing up in indexes.

The muni market includes more than 60,000 issuers and at least 1.2 million CUSIP numbers. Munis are considered less liquid than Treasury or corporate bonds. Some muni bonds never trade, and most trade infrequently. Indexes designed to reflect values in the municipal bond market rely on pricing services, such as Interactive Data, to evaluate bonds that aren’t trading.

Investors don’t necessarily always believe these pricing services: it might be that a bond that would otherwise be trading at a lower price is quoted by a pricing service at a higher price simply because nobody is trading it, so there’s no discovery of the lower price.

That explains why municipal yield-curve scales such as Municipal Market Data and Municipal Market Advisors can often disagree on where yield levels are — they are often extrapolating based on general conditions, rather than visible trades.

In fact, this disconnect is exacerbated in times of distress like November and December, when some dealers might prefer to sit on a bond position rather than liquidate it at a depressed price — even if that depressed price accurately describes the market environment.

In this sense, the more drastic selling in the ETF sector may have reflected what the lack of activity in the municipal bond sector belied, and what failed to appear in the indexes.

“You certainly could make an argument that share prices fairly represented value for the underlying asset class,” said James Colby, senior municipal strategist at Van Eck. “In absence of seeing real Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board print trades for cash bonds, we actually have a proxy for munis, and that is the tradeable equity ETF that represents the particular muni index.”

The municipal bond ETF industry was born in September 2007, when iShares brought the national fund to market. Since then, Van Eck’s Market Vectors, State Street Global Advisor’s SPDR brand, Invesco PowerShares, Grail Advisors in partnership with McDonnell Investments, and Pacific Investment Management Co. have all joined the fray.

There are now 30 municipal ETFs with $7.56 billion of assets, collectively.

Passive municipal ETFs — which represent more than 98% of municipal ETFs’ assets — strive to replicate the performance of a target index.

For instance, the iShares national fund seeks to mirror returns on the S&P National AMT-Free Municipal Bond Index.

How does a $1.9 billion fund with 1,136 bonds mimic a $537.58 billion index with 8,383 bonds? It uses a quantitative process known as representative sampling.

The fund’s managers break the target index up into risk categories, such as duration, credit rating, liquidity, and optionality. They then populate a trust with municipal bonds that in aggregate share those risk characteristics.

That way, a change in the value of the index driven by any of those risks will drive an equivalent change in the value of the trust. Both the bonds in the index and the bonds in the trust are valued by a pricing service, not always based on observable trades.

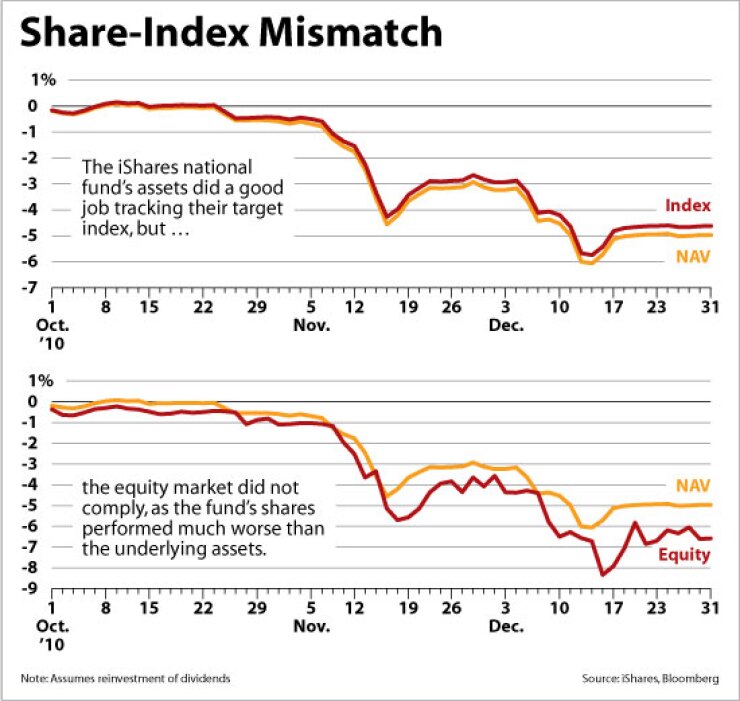

Two things can go wrong with this model. One is that the change in the value of the bonds in the trust fails to match the value of the bonds in the index. More frequently, the value of the shares representing ownership in the trust fails to match the value of its assets.

The latter was certainly the case in the fourth quarter. In general, municipal ETFs’ net-asset values did a decent job of shadowing their indexes despite the volatility. It was on the NYSE Arca — the exchange where municipal ETFs change hands — where investors determined the assets weren’t worth as much as the pricing services claimed.

ETFs’ shares traded below the quoted NAVs the entire quarter.

For example, the iShares national fund’s NAV slipped 6% in the fourth quarter. Its shares representing ownership of those assets sank 7.1%. The SPDR Nuveen Barclays Capital Short Term Municipal Bond Fund, which with $1.3 billion the second-biggest muni ETF, reported a 1.7% decline in the net value of its assets in the fourth quarter. The shares representing ownership of those assets sank 2.1%.

So why assume the ETF share traders know more than the pricing services? In many cases, the more precipitous drop in the shares preceded drops in the NAVs.

On Nov. 15, the iShares national fund’s share price was 2.4% less than the value of its assets, an unusually wide disparity. It turned out the equity price was predictive: the NAV of the trust tumbled 2. 2% in the next two days as the pricing services caught up to reality.

The same story played out in Van Eck’s high-yield fund, whose shares on Nov. 11 lagged the trust’s NAV by 4.3%. Within six trading sessions, the NAV had slid 3.3%.

Obviously not all tracking error is a premonition, but in many cases the ETF shares respond faster to changes than municipal bond indexes do.

“The authorized participants that are trading these vehicles are savvy enough to understand what the cash bond market is like, even if they’re not trading cash bonds,” Colby said. “The share price is a pretty good proxy for that cash market.”

Fang said one reason the ETF share market might be quicker to reflect changes in the municipal market is that it’s easier to trade ETFs than municipal bonds or mutual funds. ETFs also have specialists devoted to making markets in the shares, and enjoy greater institutional participation than the retail-centric municipal bond market.

Especially during periods of illiquidity, it can be difficult to find a buyer for a municipal bond. A seller often has to accept a “haircut,” sometimes several dollars per $100 par. Mutual funds, meanwhile, can only be redeemed daily, whereas ETFs trade continuously. An investor who wanted to express a bearish position on municipal bonds might find it easier to transact with ETFs than with bonds or bond funds, Fang said.

“Because of the efficiency of ETFs, people wanting to make a bet on the market may feel that with muni ETFs it’s a lot easier for them to say, we think the muni market will underperform and trade on that conviction,” Fang said. “If they tried to get ahead of it they could potentially sell their holdings in muni ETFs quicker than they would be able to in a bond fund or in municipal bond funds in general.”

Then again, another interpretation is simply that muni ETF shares fared poorly in the fourth quarter and have mostly underperformed their indexes since inception.