BRADENTON, Fla. — A federal bankruptcy judge in Tampa on Monday issued a final ruling in a developer’s Chapter 11 filing that could have a chilling effect on owners of Florida community development district bonds, observers said.

Judge K. Rodney May confirmed the reorganization plan proposed by Naples.-based Fiddler’s Creek LLC, which includes Fiddler’s Creek Community Development Districts 1 and 2 as creditors.

The districts are run by separate boards.

May accepted the debtors’ argument that bondholders should not be considered creditors and therefore had no legal standing in the case. That enabled the developer to propose a reorganization plan that restructured the municipal debt.

The ruling could set a precedent for other developers that used tax-exempt debt known as dirt bonds to finance infrastructure, to the detriment of investors in Florida CDDs, many of which are in default.

The Fiddler’s case is the first known bankruptcy case in Florida in which bondholders were not considered creditors, though the security for the bonds sold to finance infrastructure is tied to assessments on the land.

“We had everything but ground to stand on,” said Andrew Sanford, chief investment officer for ITG Holdings in Naples, which is a bondholder of Fiddler’s.

“The [reorganization] plan changed the assessment structure, and the assessments, and we didn’t have a say in it,” he said. “I think it will really be a chilling prospect for a lot of [CDD bond] buyers.”

The plan proposed by the developer restructured the amortization schedule and assessments securing roughly $100 million of defaulted dirt bonds and bondholders could not object, according to Richard Lehmann, publisher of Distressed Debt Securities Newsletter.

“The key issue at stake here is the developer put together a plan that said everybody is going to get paid and bondholders don’t need to worry,” Lehmann said. “Anybody who knows the situation with Florida CDDs knows there’s no way they will sell the remaining properties in that development at prices they would need to make everyone whole realistically.”

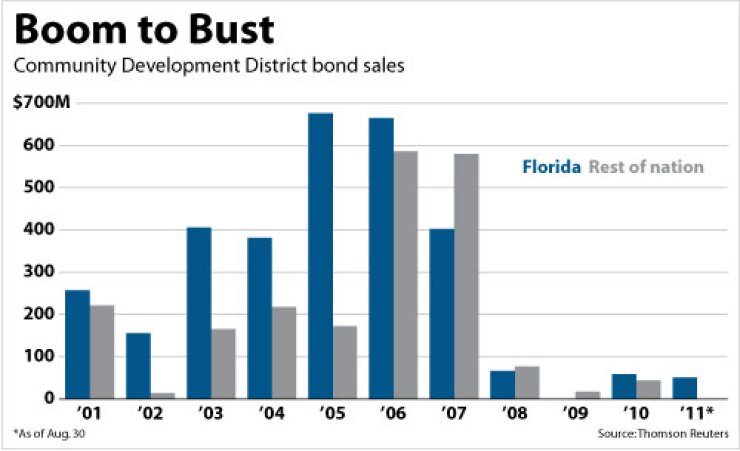

Currently, $5.1 billion, or 70%, of CDD bonds outstanding from Florida are in default, said Lehmann, who tracks defaulted municipal debt.

The real estate market crash and the tight credit market hit Florida particularly hard, with a severe impact on developers that defaulted on loans or had them called by troubled banks.

Many of the state’s troubled development districts are largely vacant except for bond-financed infrastructure such as roads and utilities.

In the Fiddler’s Creek case, the developer said prospective buyers backed out of contracts in addition to other loan problems, according to court documents.

Fiddler’s Creek LLC, whose president is Aubrey Ferrao, is a master-planned project spanning nearly 4,000 acres for 6,000 residences near Naples and Marco Island. Some 1,782 homes are built or in construction.

The development, in a wealthy area on Florida’s southwest coast, contains a range of housing products, including “custom-built luxury homes” as well as a club and spa, tennis courts, swimming pools and one golf course with a second in development.

The developer formed two CDDs that sold 10 series of unrated, uninsured tax-exempt bonds between 1999 and 2006 to finance construction of infrastructure and amenities for the project.

The 30-year dirt bonds are secured by assessments on the land that are collected on property tax bills through the CDDs, which are overseen by board members who may be appointed by the developer or elected by homeowners in the district.

Most of the Fiddler’s Creek bonds were in default because assessments had not been paid since October 2008. Assessments are paid by the developer or landowner until property is sold to a homeowner, who then begins paying the assessment.

Ferrao and his Miami-based attorney, Paul Battista, could not be reached for comment.

Fiddler’s Creek and 27 of its subsidiaries and affiliates that comprised the debtors in the bankruptcy case asserted that they had no obligation to the indenture trustee for the bonds or the bondholders, according to a disclosure document filed with the proposed reorganization plan.

Bondholders were represented by U.S. Bank NA, trustee for Fiddler’s two CDDs.

In May, the judge denied the trustee’s motion to have standing in the case, though the bank was allowed to participate in the confirmation hearing for the reorganization plan.

The court record shows that the trustee objected to many of the proceedings, and its objections were rejected by the judge.

“As trustee, it would not be appropriate for us to comment,” said bank spokeswoman Amy Frantti.

The debtors successfully proposed restructuring the bonds, as well as operations and maintenance costs of the CDD, by capitalizing unpaid and accrued interest on the bonds and pushing payments out several years. The debtors said the plan would result in bondholders being paid in full.

The restructuring plan results in a majority of the bond principal being capitalized and deferred, according to Sanford.

“We still have defaulted bonds,” he said. “There’s nothing that mandates that bondholders have to exchange their bonds. Literally, we were told to sit on our hands, and we didn’t have a say in it.”

Although the judge allowed U.S. Bank to participate in the case, he ruled that bondholders had no standing as creditors. That placed bondholders as creditors not of the debtors but of the CDDs, which voted for the developer’s reorganization plan.

Sanford and Lehmann said they believed that some or all of the district board members may have been appointed or elected by the developer.

“The district was technically the creditor organization but that was clearly a flawed arrangement because the board was elected by a majority of landowners — and that happened to be the developer,” Lehmann said, adding that the arrangement reflects a problem in the way Florida laws allow CDDs to be established and operated.

“The enabling statutes … need to be rewritten to take away from the developer the right to vote his landholding in a CDD election if he is in default,” he said.

Fiddler’s bankruptcy ruling could set a precedent for other developers that used CDDs, according to Lehmann and Sanford.

Cordoba-Ranch Development LLC near Tampa filed a Chapter 11 petition last week. It names the Cordoba Ranch Community Development District as a secured creditor though the petition does not say how much debt is owed. The Cordoba CDD sold $10.6 million of special assessment bonds in 2006 with a term maturity in 2037.

The Cordoba case is not far along enough to determine if the developer will take a position similar to Fiddler’s Creek with its bondholders.